This case was a real stumper: too many witnesses telling too many stories. Somebody needed to get to the bottom of it. It looked like I was that somebody. I stared down the witness, good old 1920. We’d been here before.

“We got ‘Ten in Interrogation A. We got ‘Thirty in C. Ya better start singing before one of them beats you to it.”

‘Twenty didn’t budge. My face was inches from his mug. He was a cool, slippery customer, like a mackerel in a bucket of ice. He held my gaze, but I could see the sweat forming in beads on his forehead.

“I want names,” I said in a low, menacing tone. I circled around to his other side. “I want dates,” I growled in his ear.

“I WANT PLACES!” I pounded the table. I pounded louder with each word. “And. I. Want. Them. NOW!”

The “NOW” echoed off the walls of Interrogation Room B, and then an ominous silence fell.

‘Twenty sat there, solid and immovable as the stony face of Everest. Then a muscle twitched in his jaw. He looked away.

I knew I had him.

Trying to get information from census reports can be tricky. Calculated birth years often vary widely from census to census. So do spellings of names, places of birth, and every other category. Nonetheless and despite their lack, census documents are often the best bet we have for finding family history.

And with a bit luck and hard work, you can learn quite a bit from a census!

Here are FIVE TRICKS to make a CENSUS SING.

1. Find a copy of the Original Document!

Bless those transcriptionists, but don’t take their word for it!

On the 1841 Scotland Census, the age of my great-grandfather Peter Martin is given as “two months.” He should have been two years old. When I finally got around to checking a copy of the actual form, I discovered the census taker had not followed instructions, and had listed Peter’s age as “2” in the male column, “2” in the female column, and “months” under occupation. Peter was indeed two years, two months old on June 6, 1841, the day the census was taken, and that was the confirmation I needed that I had found the family.

CHECK THE REAL DOCUMENT! It does make a difference.

2. Learn about THAT census. How was it taken? What day was it taken? What were its rules?

The 1841 Scotland Census is a good example. It was the first one undertaken in the United Kingdom, and it was taken like no other. Forms were distributed before June 6 to each household and collected the next day by enumerators. If household members were illiterate—and many were—the enumerator helped families fill out the form. Unique to this census, ages over 15 were rounded down to the nearest multiple of 5. So an 18 year old would be listed as 15, and a 31 year old as 30.

Peter’s father and mother were listed as being 30 and 25, respectively, with birth years of 1811 and 1816. Not even close. If I had not known about the “rounding,” I would have been very confused!

RESEARCH THE SOURCE! It does help.

2. Find the place they lived!

Finding the residence of the family members can tell you a lot! But sometimes it takes some work. On one hand, the address may be given, you find the address on Google Maps and discover the building still stands. Jackpot! The Gods have smiled upon you.

What do you do if that doesn’t work? Here are some tips:

-

-

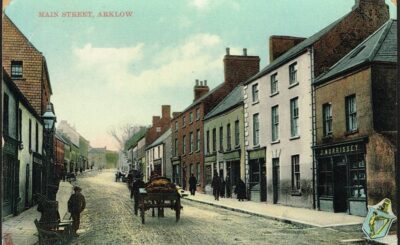

- If the building is no longer standing, look for old photos of the area. You may get lucky! Even if you don’t find the exact residence, you can get a flavor of the neighborhood and what your ancestor saw every day as he and she walked the streets.

-

- If the address is given, but the streets have changed names or numbers, find an old map of the period (ordnance maps and insurer maps are VERY helpful) or a list of the street changes by Googling (or Binging or DuckDuckGoing). That may help you find the place.

- If no address is given but you can find a good map that shows the buildings at that time, it’s possible to pinpoint the residence by following the trail of the census taker.

Here’s an example.

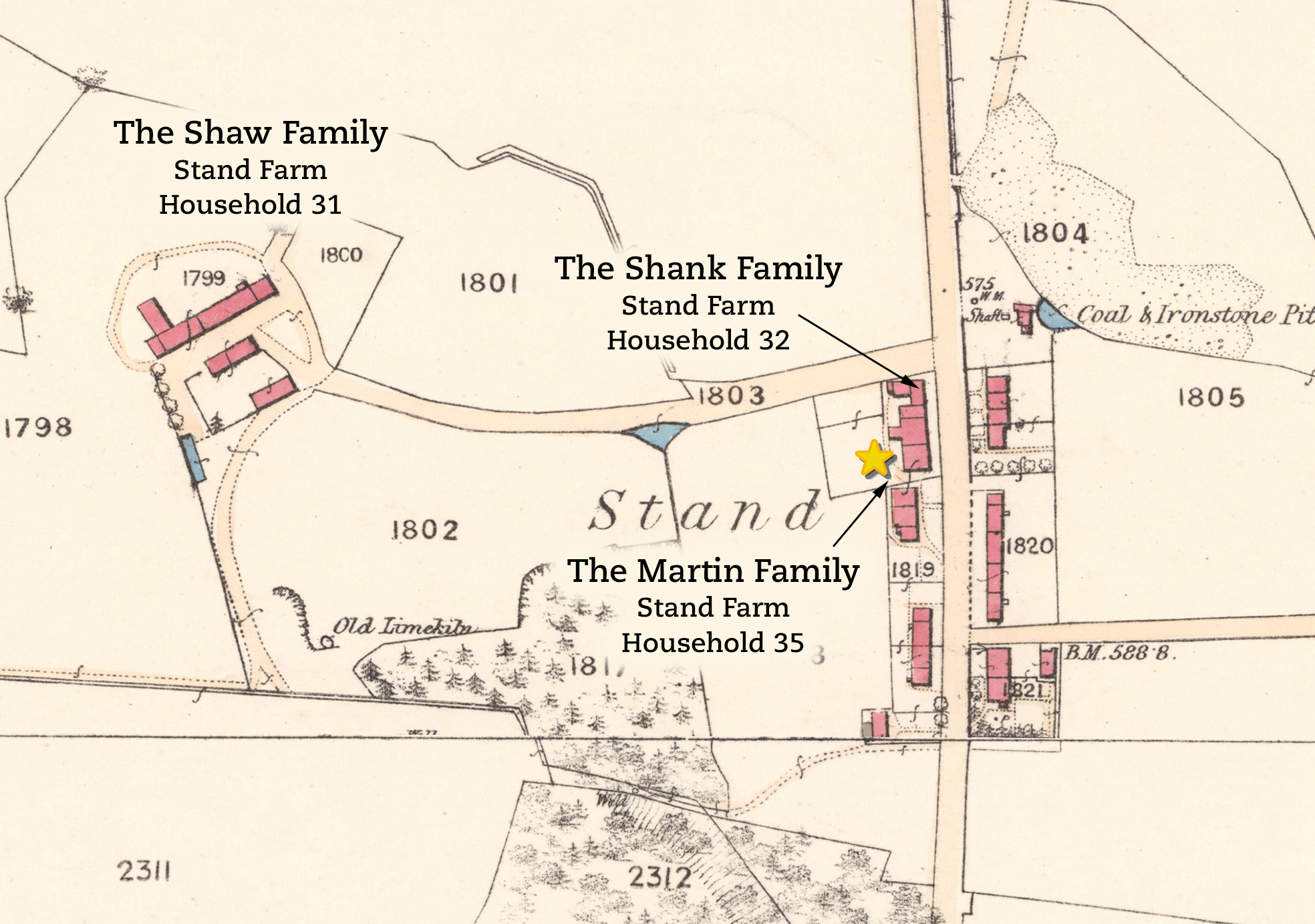

On the 1851 census, the Martin family lived in Stand, Lanarkshire, Scotland, a hamlet that lined the east and west sides of Stirling Road north of Airdrie. With persistent searching, I discovered that the east side of the road, the side near Stand Farm (transcribed on Ancestry as “Stain Farm”), was Enumeration District 6A, the one my Martin family was listed in, so that narrowed down the possibilities. (The west side, transcribed as merely “Stand,” was Enumeration District 8A.) I was also able to find an ordnance map of the area on National Library of Scotland online maps.

The census reveals that the Shaw family lived at Stand Farm with several servants and dairy maids as household 31 (page 10). The Shank family was household 32 (page 11): Richard Shanks was a “spirit dealer,” and they probably lived in the northernmost rowhouse on the eastern side of Stirling Road. My Martin family were household 35 (page 12). An educated guess places them in the fourth unit down, and as the ordnance map is to scale, we can see they lived in a 35-foot-square rowhouse.

4. Check out the neighbors.

Stand being such a small, relatively remote community, I was able to find classmates and workmates for the parents and Peter (12), Elizabeth (10) William (7), Margaret (5), and Mary (1 month), of the Martin family.

There were 20 school children aged three to 12 who lived in Stand, and other children who didn’t go to school but worked in the mines. Thomas Cleland (10) lived across the street—he was the son of William Cleland, the Underground Manager of the mine. Andrew Marshall (11) lived seven houses down from the Martin family, but he worked in coal mining instead of attending school. These two were closest to Peter in age. William was the same age as Thomas Neilson six houses down. These children’s fathers and brothers were all mine workers.

Miss Elisabeth Montrie, schoolteacher, also lived in Stand. The closest schools were at Rigend or Wallston, not quite a mile to the north or northeast. Did the children attend one of those schools or have school at Stand with Miss Montrie? Both are good possibilities. Altogether Stand contained 130 people from 26 families, of which 16 were born in Ireland. Among the men and boys, 27 had mining-related occupations, 7 were “labourers,” and 5 were “servants.”

So how did I find all that? By squeezing, poking, tickling, and cajoling that old 1851 Census until it ‘fessed up.

See Ancestry Hack #1: Follow That Census Taker!”

5. What HAPPENED NEXT? COMPARE across Censuses and FIND PATTERNS.

There are two valuable ways to compare across census years.

- First, the well-known, traditional approach: track your family from census to census and see what new information different years will hand you. This is can provide surprising results when you really analyze what’s there:

- Who is missing and why?

- Are there substantial differences in names and derived birth years?

- Are there extra relatives there and what is their relationship?

- Has income, occupation, or anything else changed?

- What does this census tell you that the last one didn’t? Year of immigration? Years married? Birthplace of parents? Citizenship status? Each of these can lead to finding new records and more information.

- Second, track the HOUSE your family lived in from census to census and see what new information pops about it and the make-up of the neighborhood.

I don’t know anybody who does that as well as the amazing Brownstone Detectives! The Brownstone Detectives delve into the history of old brownstones. Based in New York City, their research is wonderful and their blog is always a delight to read. Brian Hartig, Tom Beckham, and C. T. Bonnell use the census and other documents to track the history of old buildings. You can use their same methods to research the residence of an ancestor and find surprising things that will add to your understanding of their story.

I don’t know anybody who does that as well as the amazing Brownstone Detectives! The Brownstone Detectives delve into the history of old brownstones. Based in New York City, their research is wonderful and their blog is always a delight to read. Brian Hartig, Tom Beckham, and C. T. Bonnell use the census and other documents to track the history of old buildings. You can use their same methods to research the residence of an ancestor and find surprising things that will add to your understanding of their story.- Have the occupations, countries of origin, literacy, or economic status of residents varied much?

- Has the family moved from the previous census? Could the changing make-up of the neighborhood be the reason why?

- How many of the neighbors from ten years ago relocated and how many still claimed the neighborhood as home?

- Does the neighborhood have more or less residences than previously? Has the community or any of the streets changed names?

Shine a blinding light, and apply the thumb screws! Get in its business! Whatever it takes, get that census to talk!

-