They cut desire into short lengths

And fed it to the hungry fire of courage,

Long after—when the flames died—

Molten gold gleamed in the ashes.

They gathered it into bruised palms

And handed it to their children

And their children’s children forever.

—Vilate Raile

From a small farm upon a rocky hill in Dublin, the Brack family has spread like dandelion seeds in the wind. Jane Brack is one of the seeds that travelled furthest, settling in the broad landscape of Queensland, Australia. This is the story of Jane and the generations that followed.

Jane Brack is the daughter of Patrick Brack and Ann Mason, and the granddaughter of Anthony Brack and Rose Smyth. At some point, it is likely that all three generations lived in the stone house on the Brack farm beside the Ballycorus smelter tower. The small farm is in the townland known as Puck’s Castle, Dublin, County Dublin.

We have no birth record for Jane Brack; we gather she was born about 1859 since immigration records show her as 27 years old when she arrived in Brisbane, Australia, in February of 1886.

With the year 1859 in mind, however, a christening record for one “Julia Brack,” daughter of “Patt” and “Rose,” becomes intriquing.1 Julia’s christening was performed 1 April 1860 at Kingstown Parish, while the family was living at Ballycorus. Is it possible that Julia and Jane are the same person?

There are good reasons to believe that they are. First, Julia is one of the accepted alternate names for Jane.2 Additionally, Patrick and Anne lived in and around Ballycorus, where Patrick was employed at the smelter. And most compelling, there are no other known “Patt” or Patrick Bracks in County Dublin, nor any subsequent appearances of Julia Brack to be found. If Jane and Julia are the same person, it follows that Rose must be another name for Ann Mason.3

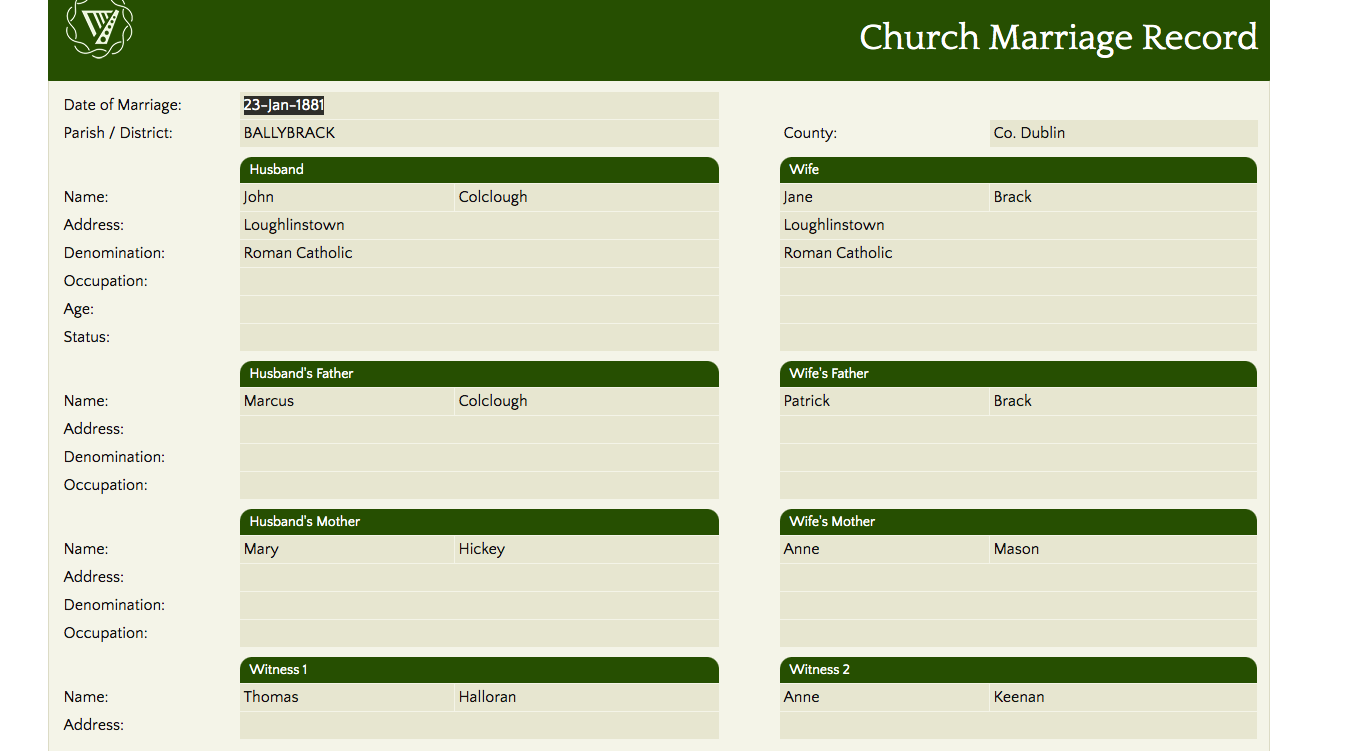

Jane married John Colclough on 23 January 1881 at Ballybrack parish. The couple was wed before witnesses Thomas Halloran and Anne Keenan.

John Colclough was born in May 1855 to Mark Colclough and Mary Hickey. John was the eldest of their seven children that include Patrick (1858 – ?), Daniel (1860- ?), Mary (1863 – 1933), James Joseph (1865 – 1947), Mark (1867 – ?), and Thomas (1869 – ?).4 John was illiterate and became a laborer like his father.

It wasn’t long after the wedding (less than two weeks, in fact!) when Jane gave birth to their first children, a set of twins, on 5 February 1881. They named the boy after John’s father, Mark, and the girl after Jane’s mother, Anne. Sadly, the twins only lived for 20 minutes.

Just over a year later, another son came to the couple; Mark II was born 14 February 1882.

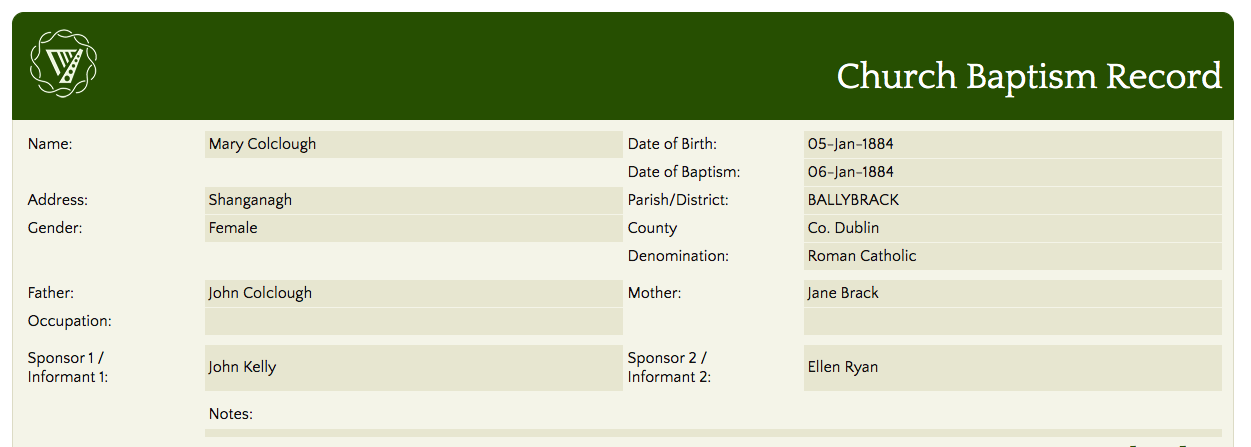

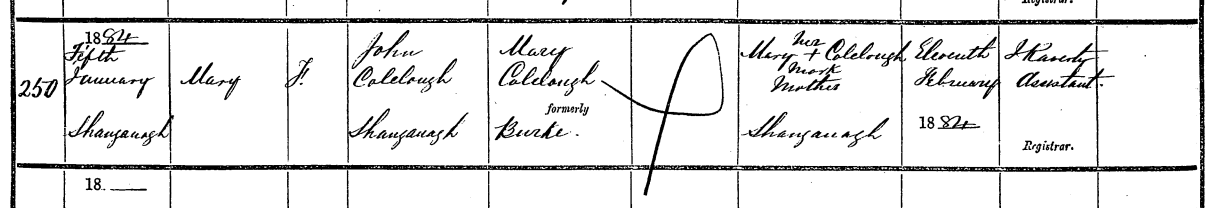

On 5 January 1884, Mary was added to the family. Her christening record shows accurate names for her parents, also giving Ellen Ryan and John Kelly as sponsors. However, the civil record oddly gives the mother’s first name as “Mary” with maiden surname of Burke.

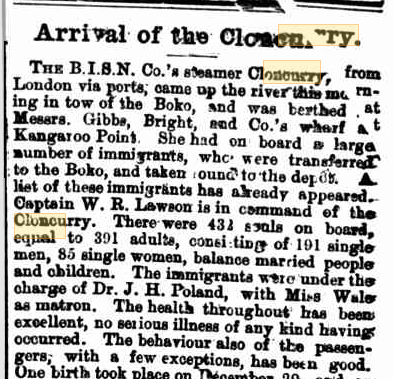

Mary was the last of the Colclough children to be born in Ireland. A year after her birth, the family of four traveled to London, where they boarded the S. S. Cloncurry for the long ocean journey to Australia.

The ship was just a year old with a large steerage area for immigrating passengers. The Colcloughs set sail on 3 December 1885, enduring 43 days at sea before reaching Batavia, Dutch East Indies (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia).5 On 29 December 1885, Jane gave birth to a daughter while at sea. They named the child Anne. On 3 February 1886, the ship docked at Brisbane with 431 souls on board: 191 single men, 85 single women, and 155 passengers who were part of a family group.6

The New Land

With the new life in the new land came a new spelling of Jane and John’s surname. The passenger manifest is the last time the records show their name spelled “Colclough.” Henceforth they were the “Cokley” family.7

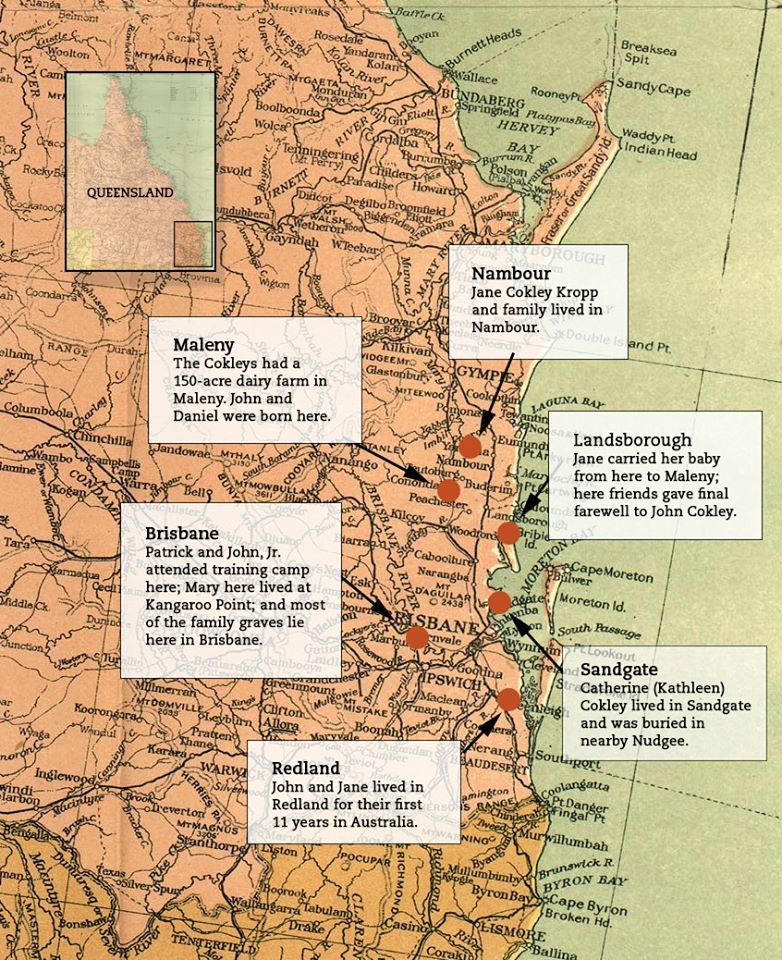

For the first 11 years in Australia, John and Jane lived at Redland Bay along the coast south of Brisbane. Five more children were born to them there, including Jane (1888), Catherine or Kathleen (1891), Patrick (1893), Thomas (1895), and Ellen (1897). During this time, John probably worked as a laborer.

In 1897, the Queensland Land Act was passed, relaxing rules for selecting land. On 9 September 1897, John Cokley applied before the Land Court to obtain 160 acres in Maleny,8 which lie some 80 miles north and inland from Redland Bay. He chose Portion 146, 150 acres on Burgum’s Road. In 1899, John and family arrived to take possession of the farm; at this point, John had only a few shillings to his name and many mouths to feed. Jane had had to walk part of the way, carrying Ellen in her arms the last 10 miles from Landsborough.9 Living in the hinterland was adventurous. John had “the experience of being attacked by a pack of dingoes.”10 The Cokley farm began as only scrubland, but John and Jane set to work to make it more.

The Burgums were the Cokley’s nearest neighbors. Mary Burgum reports, “The road into the home must have been most difficult in the district. All transport on horseback and packhorse…. John and Jane Cokley had come from lreland to Redland Bay then bought the farm property on which a small home was built in which Mrs Cokley and some of the children lived….”11

In addition to building the small home, John set about developing a fine herd of Jersey dairy cows. By 1904 the Maleny Dairy Co-Operative was formed, to which the Cokley farm supplied cream. John would load up their own dairy product and collect some of the neighbors, too, then carry it by buckboard wagon to the factory.

In Maleny, Jane and John had two more sons, John in 1899 and Daniel in 1902. That gave them 10 living children in addition to the twins who died in Ireland. The children attended school in the paddock on the Swinson’s nearby farm, as there was no other school nearby.12

Jane Cokley was a colorful character. Although in those days women were not allowed into the bar of a hotel, she was known to frequent the Maleny Hotel.13

The Cokleys and World War I

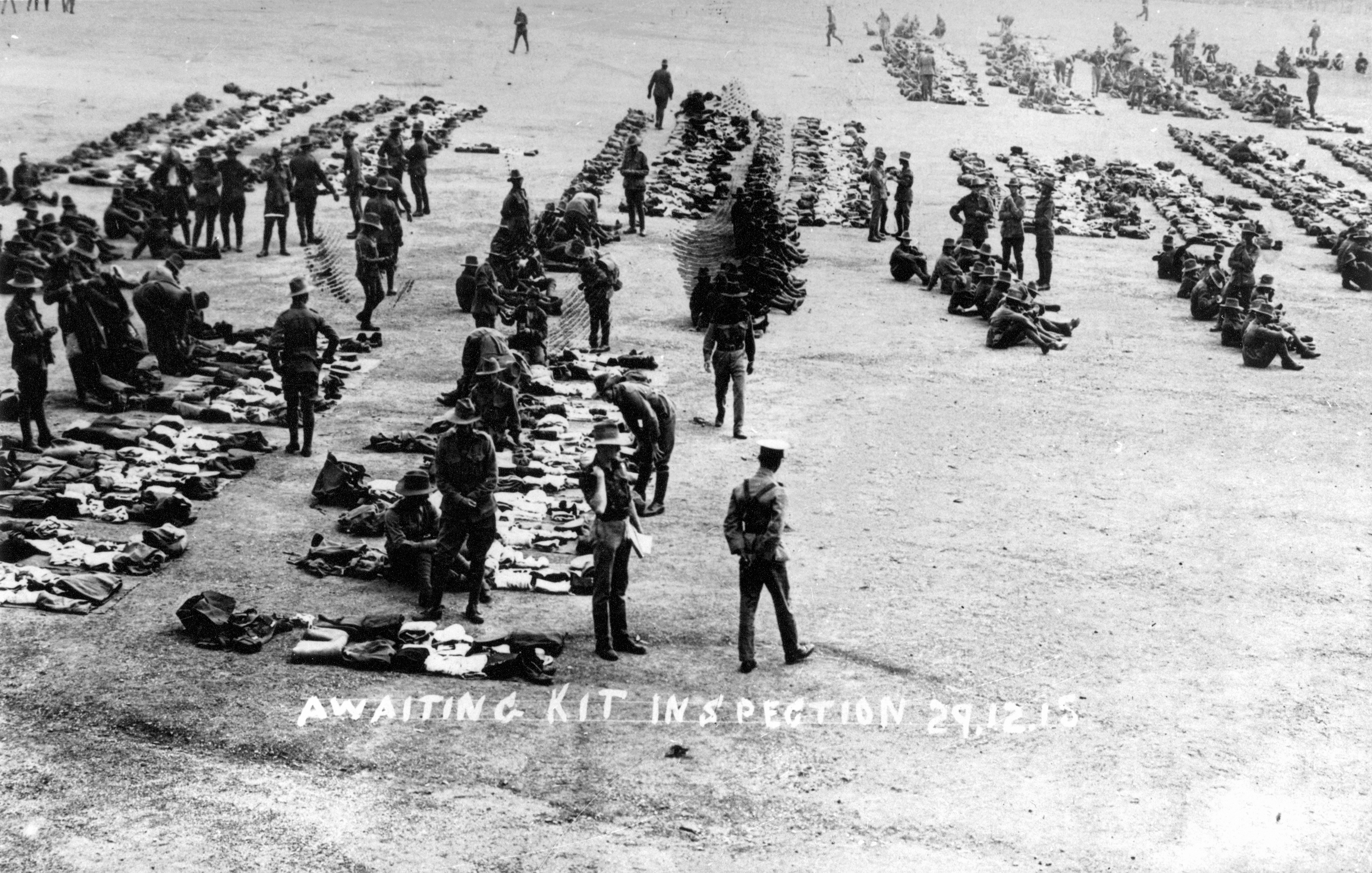

When the British Empire declared war on Germany in 1914, Australia also entered World War I. From its five million residents, Australia provided 300,000 troops, among them two of Jane and John Cokley’s sons. Patrick enlisted first, on 21 August 1915, a month shy of his 22nd birthday.

Patrick Cokley was assigned to the 15th Battalion and underwent preliminary training at Thompson’s Paddock Camp in Enoggera, Brisbane. Patrick left Australia on 3 January 1916, aboard the HMAT Kyarra, docking in Alexandria, Egypt, on 19 February 1916. Here the newly arrived troops underwent further training; then they combined with battle-depleted remnants of the 15th Battalion to form the 47th Battalion. This new battalion boarded the Caledonia, arriving at Marseilles, France, on 9 June 1916.14

John Cokley enlisted at Enoggera, Brisbane, on 6 December 1915; he and Patrick may have had overlapping stints at Thompson’s Paddock for a few months. John had declared his age as 18 years and 4 months, however, he was actually 16 years old. Interestingly, John named his mother, Jane, as his next of kin; Patrick had given their father’s name.

John Cokley was assigned to the 25th Battalion, and they left Australia aboard HMAT A16 Star of Victoria on 31 March 1916. After stops at Sri Lanka and Port Said, the ship reached Marseilles, France, on 17 May 1916. Despite enlisting months later, John beat his brother Patrick to the front by three weeks.

John was ill with influenza when he arrived at Marseille and had to be sent to the military hospital at Etaples. He rejoined his unit and was fit for duty on 4 August 1916. The very next day he fought in his first battle and suffered a gunshot wound to his arm. John was returned to the hospital at Etaples.

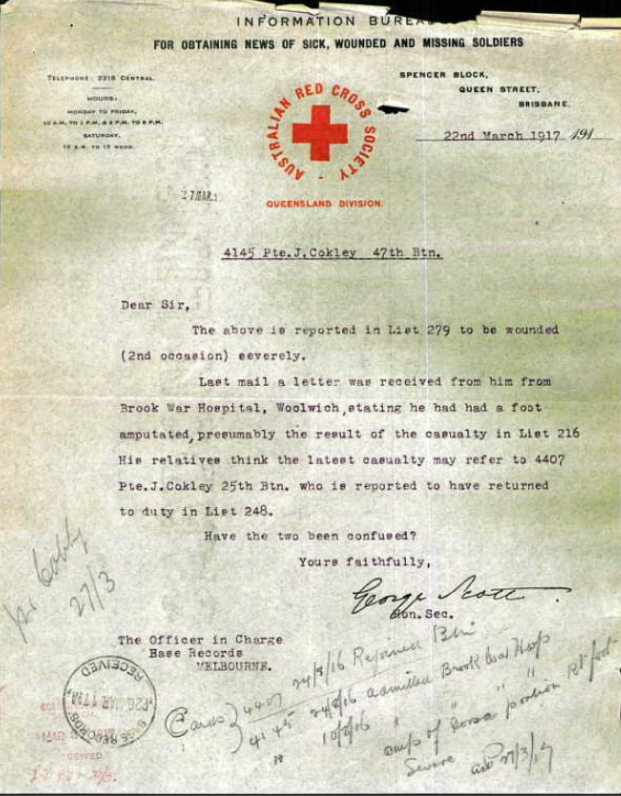

Patrick had also reached the front a few weeks before. On the day after John’s injury, Patrick was seriously wounded in action. On 6 August 1916, Patrick received gunshot and shrapnel wounds to both thighs, an arm, and both feet. The most serious damage came from a shell explosion and required a partial amputation of his right foot. Patrick’s war was over. He was sent back to England, where further amputation of the foot was required. He was then repatriated to Australia in July 1917.

Unfortunately, the family back home was not kept well informed. It took a month after Patrick was wounded for the Base Records Office to send a telegram to his father. At one point the military authorities mixed up John and Patrick and sent confusing reports to the family.15

Jane regularly read the newspaper to John Cokley, Sr. so he could stay informed on current events. During those war years he would say, “they are dropping those ‘bombs’ about and doing more of that tor-pid-o-ing.”16 And he had a right to be concerned: John and Patrick would spend months on ships traveling to and from the front, and even longer at the front dodging shells. In 1917, a photo of the two brothers appeared side by side in the newspaper giving an accurate status of their injuries.17

John rejoined his battalion on 24 August 1916, and fought at the Somme Valley in France; John also saw action at the battle of Menin Road and joined in the capture of Broodseinde Ridge in Belgium. More battles followed.

When the war ended John remained in Europe months after Armistice Day. In mid-April 1919 he was finally repatriated, reaching Sydney on 20 July 1919. From there he would travel by train to Brisbane and then to Maleny to receive a warm welcome home.

“During the first world war,” Mary Burgum relates, “the school children used to march down to the then bridge leading out of the town to welcome the soldiers who came back from the war and people from about the district would all be there…. At the welcome homes to the soldiers on the bridge, the motor cars had the kids very interested, as there were very few in the district.”18 The war and bombs and tanks were far away, but motor cars!

Back to Ireland

With war ended and the care of the dairy safely in their sons’ hands, John and Jane decided to return to Ireland for a visit in 1922. They planned first to travel to England and see the sites, then head over to Ireland to visit family, friends, and familiar haunts. Reportedly, the trip was not quite as successful as hoped: England proved to be overwhelming and Ireland had changed from what they remembered, many of their family and friends having died.19

By 1922, Jane would still have had three living siblings in Ireland: Anthony, John, and Mary Brack Kelly. John’s brothers Daniel and James Joseph had immigrated to Australia, but John still had a brother and a sister living in Ireland. So perhaps it wasn’t that the family had died, but that the reunion just did not meet their expectations.

While in Ireland, John and Jane had a photograph taken which was well received, being “the most like the way all who knew them would remember,” according to Mary Burgum.20

The trip did prove to have entertainment value: upon their return, John would recount their adventures on occasion to the amusement of the local children. As Mary Burgum recounts, “The boat put them off at Southhampton, then they took the train and were put off at Waterloo Station. Poor Cokleys, never were they in such a state of confusion.

“Old John said ‘at last I said “Mother sit on the luggage and I will go and see if can get someone.” ’ As he started off, he said, ‘A voice said, “[I]s that you John?” ’

“ ‘Be God it is,’ says I. [N]ever was I so glad to see a man in my life! It was Ted Smith who I had worked for at Montville about 40 years ago. John continued, ‘I nearly jumped “six toot in the air.” ’

“Ted Smith took over, had the luggage put on the boat for Ireland and gave Cokleys a ride in a taxi around London before the boat left. He met them when they came back from Ireland and put them on the boat for Australia.” 21

Selling the Farm

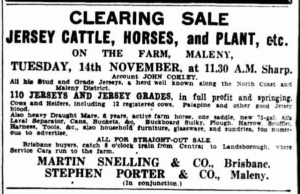

When John Cokley returned from Ireland, he appears to have decided to retire from dairy farming. On 11 December 1925, the Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser printed a display ad announcing a clearing sale at Cokley’s farm. The ad included this note: “Mr. Cokley has leased his farm, and wishes to announce that the above is for straight-out sale.”22 The sale included Jersey cows and a Jersey stud, horses, pigs, and equipment. However, the lease, and thereby the sale, evidently did not take place, as eight years later another sale was announced in The Courier-Mail of Brisbane, Queensland, on 21 October 1933.23

In those eight years, the offering of cows for sale (and probably the size of the herd) had grown from 63 to 110 cows, heifers and bulls. This time the sale went through, with all animals, equipment, and household items purchased at auction.24

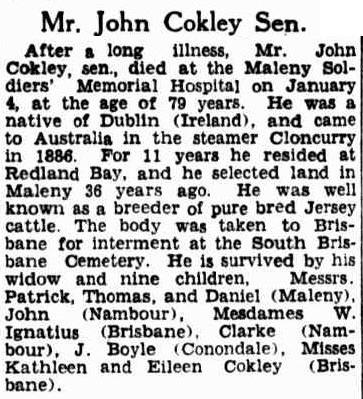

At some point, John Cokley’s health had deteriorated and he entered the Maleny Soldiers Memorial Hospital for “a long and painful illness.”25 There John passed away on 4 January 1934, six weeks after the farm sale was held. By this time, John and Jane Brack were well respected and recognized as pioneers of Maleny. According to John’s obituary, “The body was taken by train from Landsborough for interment at the South Brisbane cemetery. Many old friends attended at the station at Landsborough, and later at the graveside.”26

The obituary, however, contained two errors. It claimed that John had two sons that predeceased him. In fact, he had two sons and a daughter. Twins Mark I and Anne I had died shortly after birth in Ireland in 1881. The second son, Mark II, had died on 4 July 1908 while the family lived in Redland Bay. Mark was living with his uncle Daniel Cokley who was a cab driver at No. 53 Charlotte Street, in Brisbane. Mark was 26 years old.27

He was buried at Toowong Cemetery in Brisbane, Queensland.28

The second error is the claim that John had a living sister in Ireland. Although the family in Australia could hardly have known, Mary Colclough Donohue had passed away of heart failure three weeks before John on 16 December 1933 at Loughlinstown, Dublin, Ireland.29

After John’s death, Jane lived with daughter Mary Cokley Ignatius at Kangaroo Point in Brisbane. It wasn’t long before tragedy struck the family again. Patrick Cokley—the son who had had a foot amputated in World War I—died on 23 March 1935 at Soldiers Memorial Hospital in Maleny. He was 42, had never married, and had been working as a farm laborer in Woodford.30 He was buried at Toowong Cemetery in Brisbane.31

Jane would follow her husband and son to the grave later that year on 12 October 1935. She was buried with her husband, John.32

The Next Generations

Mary Cokley—Mary married Walter Ignatius on 9 November 1910. Walter was born in Brisbane, Australia in 1874, son of Pablo Fevelo Ignatius of Manila, The Phillippines, and Emma Ann Isabella Routledge of Brisbane.

When Walter was 16, he had an unfortunate brush with the law. He and six other youth were charged in a racist encounter as they were caught stoning Lascars (Indian sailors) at Kangaroo Point.33

Walter appeared to be a man of several talents, including curing dugong hides. In an 1897 court case, Albert Gibbons was charged and fined for obtaining by false means two hides that Walter Ignatius had been commissioned to cure.34

At the time of Mary and Walter’s marriage in 1910, Walter was head fireman aboard the steamer Emerald. The day before the wedding, the ship’s owners and his fellow shipmates presented him with a clock to commemorate the occasion.35

Walter and Mary lived in Oxley until their deaths. They had one daughter, Phyllis Monica Ignatius, in 1912. Walter continued to work as a fireman right up until his death on 23 November 1931, judging by electoral rolls.36 Mary died on 31 October 1963. Both were buried at the South Brisbane Cemetery.37

Annie Cokely—Annie married James Albert Clarke on 16 January 1903 in Queensland. James was born in 1882 at Brisbane, the son of Emma James and James Clarke, both having immigrated to Australia from England. James Albert served for 11 years with the Moreton Infantry, and on 14 December 1915, at age 35, he enlisted for the Australian Imperial Force to fight in World War I. At that time he gave his occupation as “cook,” and declared that he and his wife had been living apart for three years. On the 1912 Electoral Roll, however, Annie and James were registered at the same address in Oxley, and his occupation then was “mechanic.”

James’ service career was unillustrious. He was cited twice for desertion, the first time absent without leave for one day on 20 February 1916. The second time he was gone for some indeterminate amount of time beginning 1 March, although he was only charged with one week’s absence on 14 March 1916. James wrote an urgent letter to “G. C. A. Comfy,” explaining, “The reason I am not in camp is because when I got home I found things and my Father in a very bad state and under quarantine and I am also the same….”3 There is no further record of James either shipping out or receiving discipline for his lapse. His father died a year later in July 1917.

It appears Annie and James did not have children. Annie died on 1 April 1947; James followed on 15 March 1951. Their burial places are not known.

Jane Cokley—Jane married Alfred Kropp on 27 November 1907. Alfred was born to Maria Magdaline Kropp on 2 April 1887; Maria married James McNab the following year on 27 July 1888. Jane and Alfred Kropp made their home in Nambour where he was a farmer. Alfred Kropp died on 29 June 1924 while the youngest of the five Kropp children was only nine years old.39

Jane and Alfred Kropp had five children: Jane Veronica Kropp (1908 – 1910) died as a child; Esther Kropp (1910 – 2005) married Richard Thomas Alcock (1908 – 1974); Allan (1912 – 2003) married Joyce Annie Jacobs (1921 – 1975); Edward Ralph Kropp (1917 – bef. 2017) was a fireman and married Eileen May O’Shea (1914 – 1977); and Thelma Cokley Kropp (1915 – 2015) married William Ernest Walters (1920 – 1984).

In the year following Alfred Kropp’s death, Jane married James Boyle who was a dairy farmer in Connondale, a dozen miles east of Maleny. James was born 28 April 1881, the son of James Boyle and Elizabeth Hughes who immigrated from Ireland in 1866.

James appears to have been a prosperous farmer and well engaged in the community. He donated an acre of land and chaired the committee to erect a community hall in 1929.40 Two years later, the Hall of Arts in Maleny was the site of a coming-of-age party for daughter Esther Kropp (her 21st birthday): “The guest of honour wore a Swiss hand-embroidered white linen frock, while her mother was frocked in navy blue crepe de Chine, with mastic trimmings.” The 150 guests present were treated to dinner, a three-tiered cake, and dancing to music supplied by the Nambour orchestra. And what is a birthday without gifts? Esther was presented “a diamond studded gold key, in the form of a brooch.”41

Jane and James had one child together, Eileen Esme Alice Boyle, born 9 January 1927 at Conondale.42 Eileen married, however, no information is known about her husband. Eileen died 30 March 2002.

Jane Cokley Kropp Boyle died 30 March 1956. James Boyle followed her on 1 May 1970. They were buried together at the South Brisbane Cemetery, Brisbane.43

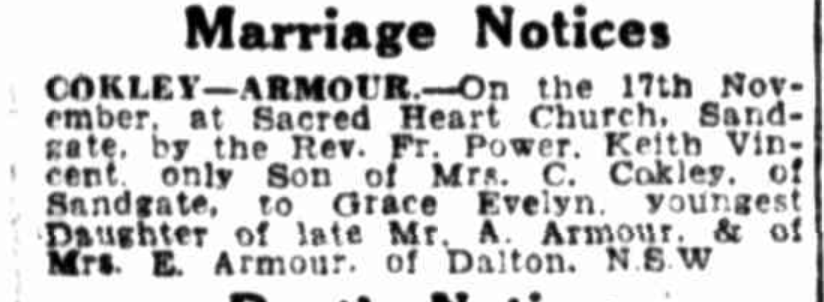

Catherine Cokley—Catherine apparently did not marry: she is listed as “Miss Kathleen” in her father’s obituary in 193444 and her grave is marked with her maiden surname.45 However, Kathleen did bear two children: Frances Josephine Cokley (1916–1987) who did not marry; and Keith Vincent Cokley (1921–2003) who married Grace Evelyn Armour (1922 – 20). Grace was attended by Miss Frances at the wedding.46

Catherine/Kathleen died 9 November 1966 and was buried at Nudgee Cemetery in Brisbane, Queensland.47

Thomas Cokley—Thomas worked as a laborer after the dairy farm was sold, and is found in various locations around Brisbane on the electoral rolls.48 At some time before 1954, Thomas may have married a woman or fathered a daughter named Ivy Lillian. She is found at the same address as Thomas, occupation “home duties,” on the 1954 voter rolls in Nundah, Queensland. As the voting age in 1954 was 21, Ivy was born no later than 1933. Nothing more could be found about them. Thomas died 2 August 1978 and is buried at Nudgee Cemetery in Brisbane. Ivy Lillian Cokley died sometime after 1980.49

Eileen Cokley—There is no record of a marriage for Eileen, however she appears regularly on electoral rolls. In each, her occupation is given as “house duties.” Her last appearance in the electoral rolls is in 1937, at the Albion Hotel on Sandgate Road.50 Nothing more could be found about Eileen.

John Cokley—After John’s return from the war outlined above, he married Ruby May Lowrie on 30 June 1920. Ruby May was born in 1899, the daughter of James Lowrie and Maria Barkley. The newlyweds lived in Maleny and John continued to work his father’s dairy farm. Not long after father John and brother Patrick passed away, Ruby also died on 19 November 1934. She was only 35 years old. She was buried with her parents and siblings at Toowong Cemetery in Brisbane, Queensland, leaving him with four children aged 13 and under.

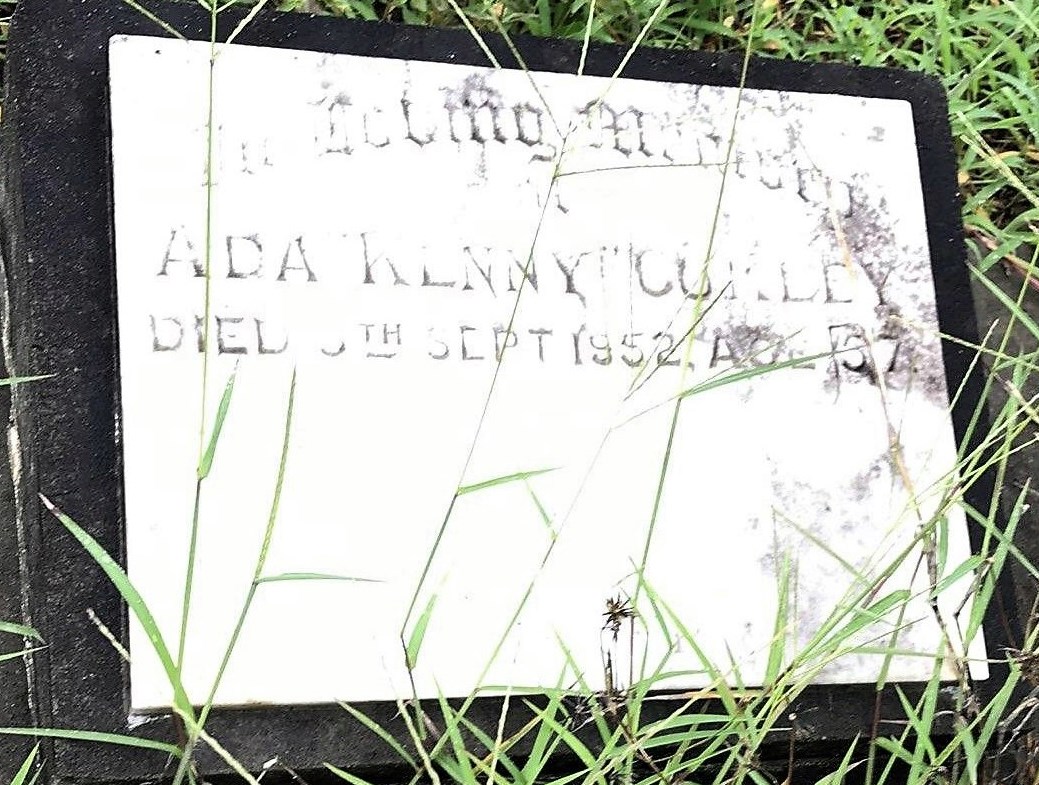

With the farm sold, John moved to Brisbane and worked at the docks. At some point he married Ada Milward Kennedy, daughter of Thomas Milward and Mary Ann Hendy. She died on 5 September 1952. John Cokley lived until 2 January 1973; he was buried at Toowong Cemetery in the same grave as his second wife.51

John Cokley, Jr. and Ruby May Cokley had four children: Terence Mark Cokley (1921-1987) married Winnifred Ethel Richardson (1925–1957); John (Jack) Cokley (1924 – 2011) married Dulcie Desma Harvey (1928–1995); Maureen Josephine Cokley (1932 – ?) married Kevin Patrick Ryan (1925–2006); and Eileen Cokley for whom we have no further information.

Daniel Cokley—Daniel married Theresa Euphemia, last name unknown, date and place of marriage also unknown. Daniel signed up to serve in World War I, but not much is known about his service. He enlisted at Mackay, Queensland and his service number is QX18751. From that we know he was in the Army, and volunteered to fight in Europe. Also, he was an early enlister judging by the lowness of the service number. Daniel and Theresa appear on the electoral rolls in 1972, however, no occupation is listed for either.52 Daniel died on 6 May 1975 (aged 72) and was buried at Mount Gravatt Cemetery and Crematorium, Brisbane.53

Here is where I close the story of the Jane Brack and John Colclough family in Australia. But of course, the story never ends. Generation after generation will continue to spring forth from the seeds of industry and sacrifice they planted in a strange and hostile land, a land so very far from home. Australia gave the impoverished couple what 19th Century Ireland never could—land and opportunity. And they have given their children ever so much more.

NOTES

1.This christening record is only found on the RootsIreland.ie website. The record image is not available online, so I have not been able to verify the accuracy of the transcription.

2. “First name variants from Irish Genealogical Records,” RootsIreland.ie, www.rootsireland.ie/help/first-names. Visited 20 April 2020.

3. Notably, none of Anne’s children were named “Anne,” although one was given the name “Roseanna.” Could Anne’s complete name have been Rose Anne? With the sparseness of records in Ireland, these kinds of questions can be posed but rarely fully answered.

4. Christening records show seven children for Mark Colclough and Mary Hickey, although John’s obituary only indicates five siblings. Perhaps one of the children died in childhood and was not considered in the obituary. Daniel and possibly James Joseph also immigrated to Australia.

5. See “Arrival of the Cloncurry” for more an in-depth description of the ship. Brisbane Courier, Thursday, 8 January, 1885, p. 5.

6. “Arrival of the Cloncurry ,” The Telegraph, Brisbane, Wednesday, 3 Feb 1886, p. 4.

7. See entry for John Colclough, Ship: SS Cloncurry; Arrival: Brisbane, 3 February 1886; Queensland State Archives; Registers of Immigrant Ships’ Arrivals; Series: Series ID 13086; Roll: M1701.

8. “Brisbane Land Court,” The Brisbane Courier, Friday,10 September 1897, p. 2.

9. “Dairying in the Maleny District,” The Queenslander, 1 March 1924, p. 15.

10. Ibid.

11. “The Burgum Story,” Mary Burgum, Maleny News, Queensland, Australia, 1984.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. There are three good sources for information about the Cokleys’ wartime experiences. All were used in this document. The first two are bios for John and Patrick from the “Adopt a Digger” website: (http://www.adoptadigger.org/search-for-a-ww1-digger/search-for-a-ww1-digger/item/3-diggers-database/430-cokley-john and http://www.adoptadigger.org/search-for-a-ww1-digger/search-for-a-ww1-digger/item/3-diggers-database/2356-cokley-patrick). Visited 20 April 2020. The third source is the cache of military records found on Ancestry.com. (Ancestry.com. Australia, WWI Service Records, 1914-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: National Archives of Australia: B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia.)

15. Image 587, Patrick Cokley Service Record, Ancestry.com. Australia, WWI Service Records, 1914-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: National Archives of Australia: B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia.

16. “The Burgum Story,” Mary Burgum, Maleny News, Queensland, Australia, 1984.

17. Daily Standard, Brisbane, Saturday, 12 May 1917, p. 12.

18. “The Burgum Story,” Mary Burgum, Maleny News, Queensland, Australia, 1984.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. “Special Opportunity,” Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, Friday, 11 December, 1925, p.6.

23. The announcement appeared in other newspapers, also.

24. “Everything Sold,” The Courier-Mail, Wednesday, 15 November 1933, p. 7.

25. Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, Friday, 12 January 1934, p. 5.

26. Ibid.

27. “Funeral Notice,” The Telegraph, Brisbane, Monday, 6 July 1908, p. 6.

28. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/205843776/mark-cokley. Visited 20 April 2020.

29. Mary Donohue, General Register Office, Rathdown SR District/Reg Area, Group Registration ID 1925797, 16 December 1933. Record accessed through www.irishgenealogy.ie. Visited 20 April 2020.

30. “Maleny,” The Courier-Mail, Wednesday, 27 March 1935, p. 4.

31. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/205844496. Visited 20 April 2020.

32. John and Jane Cokley were buried at the South Brisbane Cemetery, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. (Find a Grave, “John Cokley, Sr. Memorial,” https://www.findagrave.com/ memorial/50970522/john-cokley).

33. The Brisbane Courier, Friday, 7 March 1890, p. 5.

34. “Accidents and Offences,” The Brisbane Courier, Tuesday, 4 May 1897, p. 3.

35. “Fish Board,” The Brisbane Courier, Wednesday, 9 November 1910, p. 11.

36. Australian Electoral Commission. [Electoral roll]. See Walter Ignatius in Maree, Oxley, Queensland, Australia, 1931.

37. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/48741757/walter-ignatius. Visited 20 April 2020.

38. Image 47820, James Albert Clarke Service Record, Ancestry.com. Australia, WWI Service Records, 1914-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: National Archives of Australia: B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia.

39. A memorial notice placed 14 years after Alfred’s death reads, “In loving memory of our dear Dad, Alfred Kropp, who passed away at Maleny, June 29, 1924. Although his voice is silent, And his smile we see no more, In our hearts his memory lingers, Just as fondly as before. Inserted by his loving Children” (The Courier-Mail, Wednesday, 29 June, 1938, p. 12).

40. “New Public Hall,” Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, Friday, 17 May 1929, p. 6.

41. “Coming of Age Party,” Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, Friday, 27 November 1931, p. 8.

42. “Births,” The Brisbane Courier, Saturday, 12 February 1927, p. 16.

43. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/48737759. Visited 20 April 2020.

44. “Funeral Notice,” The Telegraph, Brisbane, Monday, 6 July 1908, p. 6.

45. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/183373358/catherine-cokley. Visited 20 April 2020.

46. ”Cokley—Armour,” The Telegraph, Brisbane, Wednesday, 21 November 1945, p. 4.

47. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/183373358/catherine-cokley. Visited 20 April 2020.

48. Australian Electoral Commission. [Electoral roll]. See years 1919, 1925, 1936, 1937, 1943, 1949, 1954, 1958, 1963, 1968, 1972, and 1977. Ivy Lillian appears at the same address with Thomas Cokley from 1954 through 1977. She also appears in 1980, which is the last year available.

49. 1980 is the last year I have found a record for Ivy.

50. Australian Electoral Commission. [Electoral roll]. See years 1919, 1920, 1922, 1930, and 1937.

51. Photo added 31 December 2019 by Donna J. Sullivan. Evidently John’s name had not been added to the stone at the time the photo was taken. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/205844027/john-cokley. Visited 20 April 2020.

52. Australian Electoral Commission. [Electoral roll]. Daniel Cokley in Division of Bowman, Queensland, 1972.

53. Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/204694141/daniel-cokley. Visited 20 April 2020.