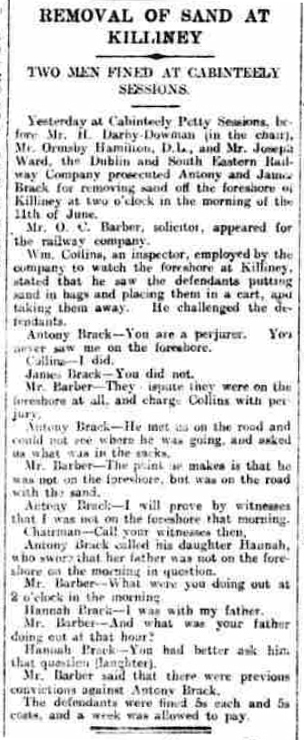

Two Men Fined at Cabinteely Sessions

Yesterday at Cabinteely sessions, … The Dublin and Southern Eastern Railway Company prosecuted Anthony and James Brack for removing sand off the foreshore of Killiney at 2 o’clock in the morning of the 11th of June.

William Collins, an inspector, employed by the company to watch the foreshore at Killiney, stated that he saw the defendants putting sand in bags, and placing them in the cart, and taking them away.

Anthony Brack—”You are a perjurer. You never saw me on the foreshore.”

Collins—”I did.”

James Brack—”You did not.”…

Anthony Brack—”I will prove by witnesses that I was not on the foreshore that morning.”

Chairman—”Call your witnesses then.”

Anthony Brack called his daughter Hannah who swore that her father was not on the foreshore on the morning in question.

Mr. Barber—”What were you doing out at 2 o’clock in the morning?”

Hannah Brack—”I was with my father.”

Mr. Barber—”And what was your father doing out at that hour?”

Hannah Brack—”You had better ask him that question.” [Laughter].

When the family historian is faced with a complex family puzzle, one with lots of stray, confusing pieces, it’s natural to want to simplify the problem. We look at the pieces we know and are familiar with and exclude stray variables that muddle the brain. Like a jigsaw puzzle, it’s easier to put together the faces or the birds before tackling the grass and the sky. However, if while we’re focusing on the easier pieces we let the harder bits fall under the couch and lie forgotten, that’s a problem!

Here is a case study that shows how easy it is to make that mistake.

In Ireland’s Dublin and Wicklow counties, we find families with the surname Brack scattered here and there in the 19th and 20th centuries. Are they branches of the same tree? Probably, although the family tie-in is not always apparent. The Brack family at Dean’s Grange is a perfect example; sparse records and the abundance of similarly named Bracks make it tricky to place the Dean’s Grange Bracks into the rest of the family tree.1

Here’s what we learn about Anthony Brack of Dean’s Grange from parish and census records; Anthony was born in 1863 (1901 census) or 1871 (1911 Census) in County Dublin. He married Mary Jane Byrne of County Wicklow around 1883 (possibly in England, where their first child, John, was born in 1885 or 1890, depending on the census). Anthony and Mary Jane had additional children Mary (1887), Hannah (1889), James (1890), Catharine Mary (1893), Margaret (1896), and Anthony (1898); these later children were christened at the Catholic Church at Cabinteely.

Piece It Together!

Fortunately, this family of Bracks were a rascally lot and appear quite frequently in newspaper, court, and prison records—but then, Bracks from other places do also! We can extract important bits of information from Father Anthony Brack’s escapades. He was a carter, providing and hauling hardscape in his cart that was pulled by a horse or jennet.2 He creatively filled many of his customers’ needs for sand and gravel by helping himself to what he found at the beach or along the railway tracks. (Sound familiar? The Brack family at Puck’s Castle did the same thing!)

SEE A Study: Anthony Brack and His House at Puck’s Castle

Court and prison records tell us that Anthony of Dean’s Grange:

- Was relatively tall, about 5’8″, and weighed 185 lbs.

- Was born at Ballycorus and could read and write.

- Had brown hair and brown eyes, varicose veins, and a wart on his thumb!3

To his credit, Dean’s Grange Anthony’s indiscretions were at least ones of industry. He was rarely found drunk on the streets or beating his wife as other Anthonys were. His offenses included allowing animals to wander free (horses, a goat, a cow, and a jennet), and helping himself to sand, gravel, and even oats and bran.

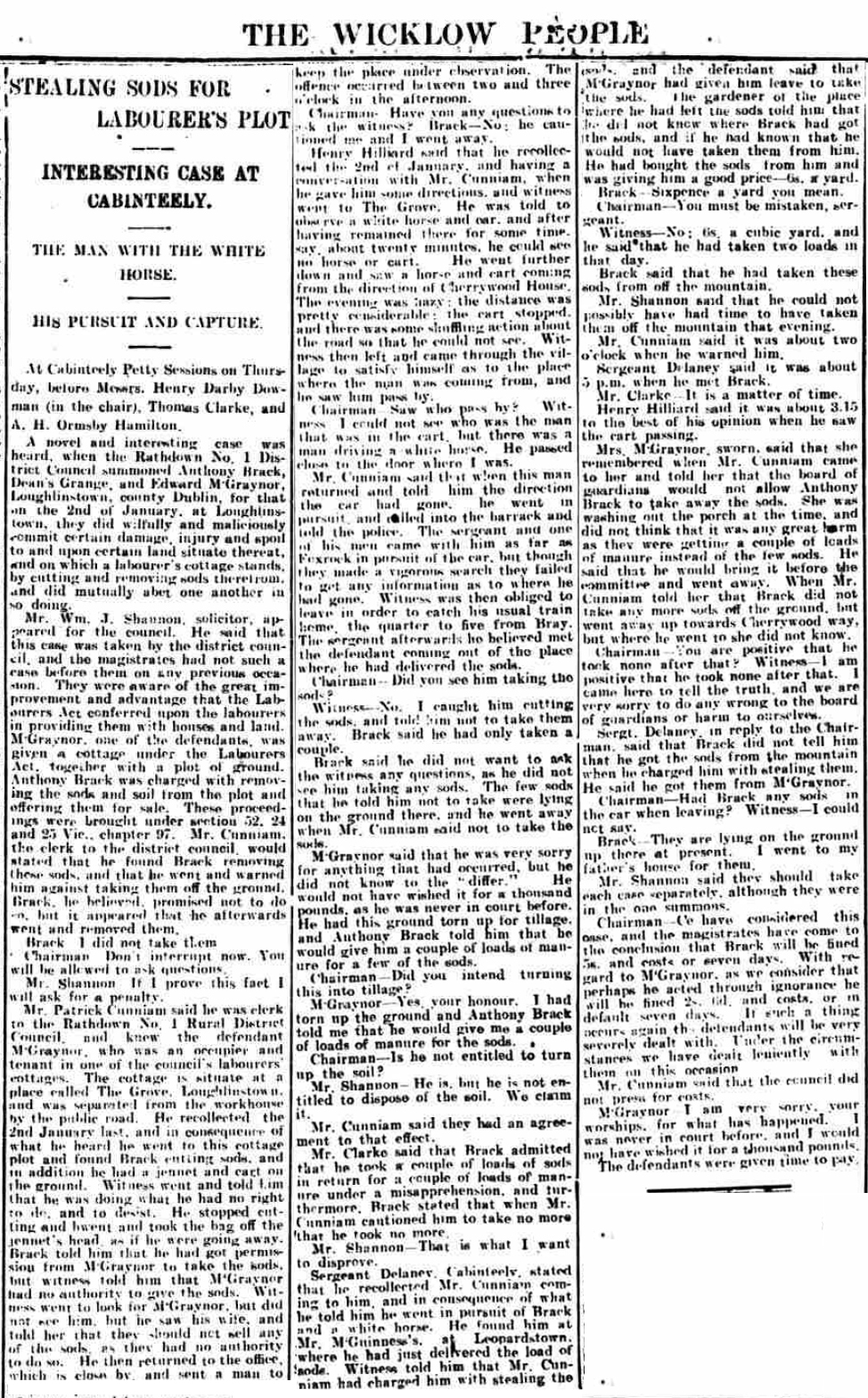

In 1908, Anthony expanded his takings; he was caught removing sod from a newly built, council-owned worker’s cottage. Brack made a deal with the occupant, Edward McGraynor, to trade the sod for a few loads of manure. McGraynor was all for it—he wanted to till the land and needed manure but not sod. However, the mutually beneficial arrangement did not meet the council’s approval.

Anthony was warned he wasn’t allowed to take the sod by council clerk, Mr. Cunniam. Anthony stopped what he was doing, but later snuck back and took the sod anyway. A comical chase ensued: “Follow the man with the white horse!” the clerk ordered.

The constabulary chased Anthony as far as Foxrock, but lost his trail, later apprehending Brack after he had sold and delivered the sod to a gardener. Brack’s later testimony before the court was evasive, imaginative, and held little truth.

“You came back for more sod!”

“I only took a few that were lying on the ground. I stopped when I was told to.”

“You took two loads that day.”

“I got them off the mountain.”

“You sold them for 6s a yard!”

“You mean 6p.”

Despite Anthony’s wily responses, he was found guilty and fined.4

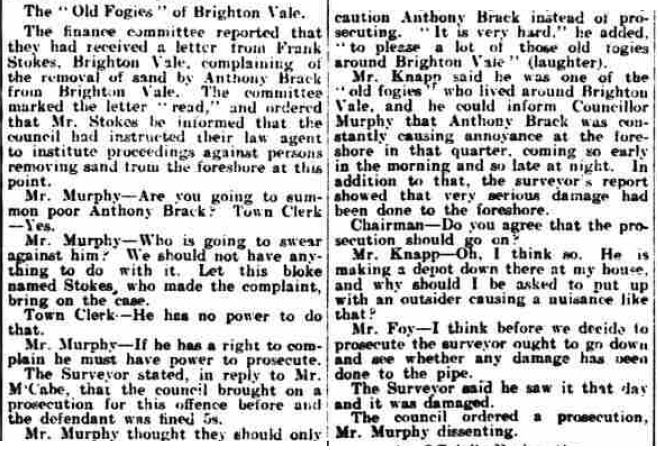

In addition to being a nuisance to the constables and railroad authorities, Anthony managed to annoy homeowners with his aggressive collection methods. In 1913, Mr. Stokes wrote a letter to the Blackrock Council complaining that Anthony Brack was removing sand from Brighton Vale. Councilor Murphy didn’t want to be bothered with the issue, saying, “It is very hard to please a lot of those old fogies around Brighton Vale.”

But Mr. Knapp insisted, saying he was one of the “old fogies” from Brighton Vale and Anthony Brack was “constantly causing annoyance in the foreshore at that quarter, coming so early in the morning and late at night…. He is making a depot down there at my house.”

When the Surveyor confirmed that damage was being done to the foreshore, the Council voted to prosecute. Mr. Murphy, however, dissented.5

But Anthony isn’t only recorded for misdeeds. He also shows up in Workhouse records with a contract to bring in sea gravel for the cemetery walkways. (And which beach did that come from?) He was paid 1£ 12s for the job. He also appears on one court document as a witness for a sergeant whose jacket was stolen.6

Unfortunately for Anthony, involving his children in his dishonesty may not have been such a good idea. Two of his sons, James and John, were arrested and jailed on separate occasions for breaking and entering, larceny, and public drunkenness. And although records show Anthony could read and write, those two sons could not, according to prison records.7

Three of Anthony and Mary Jane’s daughters married: Margaret to James Cuddihy, Hannah to John Caffrey (producing at least one child, James Joseph Caffrey), and Cathryn Mary to Matthew Brennan. If we can locate some of their offspring and compare their DNA with Brack descendants from known lines, we could verify the family relationship. But no luck as of yet.

It’s Complicated

So where did this Anthony come from? Who were his parents?

Fortunately, although we don’t have a marriage record for Anthony Brack and Mary Jane, we do for Anthony’s second marriage. Mary Jane died in 1921 and Anthony remarried widow Ellen Curtis Mooney in 1932. On their marriage record, Anthony’s father’s name is recorded as “John Brack” and is not marked as “deceased” (as Ellen’s is) so presumably he was still living (although that would have made him 111 years old!)8

I admit to getting excited about this new development—what a great solution! Could Dean’s Grange Anthony be the son of John Brack, son of Anthony Brack of Puck’s Castle? John and Hannah are notably missing a son named Anthony among their nine children. It all made good sense. John of Puck’s Castle and Anthony of Dean’s Grange were a generation apart, were both carters who acquired product from the same places. Logically, John of Puck’s Castle should have named one of his first children after his father, from whom he inherited the land. Perfect fit!

From Complicated to Confused

I was feeling very clever about this solution until I found another newspaper article.

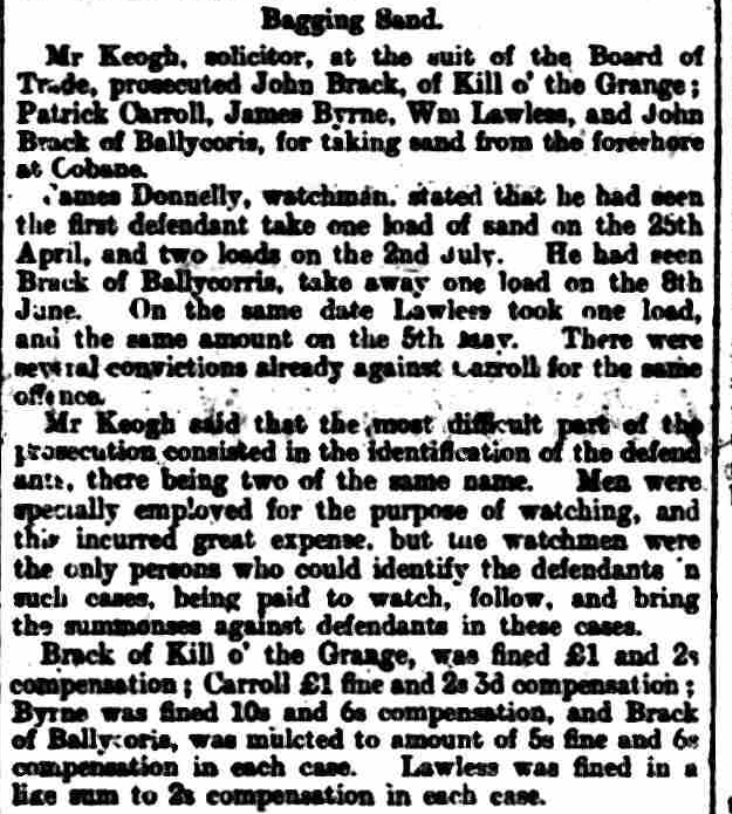

Bagging Sand

“Mr. Keogh, solicitor, at the suit of the Board of Trade, prosecuted John Brack, of Kill o’ the Grange , Patrick Carroll, James Bern, William Lalas, and John Brack of Ballycorus, for taking sand from the foreshore at Cobane.

“James Donnelly, watchman, stated that he had seen the first defendant take one load of sand on 25th April and two loads on 2nd July. He had seen Brack of Ballycorus, take one load on the 8th June. …

“Mr. Keogh said that the most difficult part of the prosecution consisted in the identification of the defendants, there being two of the same name. Men were specially employed for the purpose of watching, and this incurred great expense, but the watchmen were the only persons who could identify the defendants in such cases, being paid to watch, follow, and bring the summonses against defendants in these cases.” 9

Evidently, there were two sand-carting John Bracks on the loose on the shores of County Dublin, one at Dean’s Grange and one at Puck’s Castle. My theory was sunk! However, once I processed this new information, I remembered there was another John Brack born at Puck’s Castle.10

The Case of the Man Who Was Twice Christened

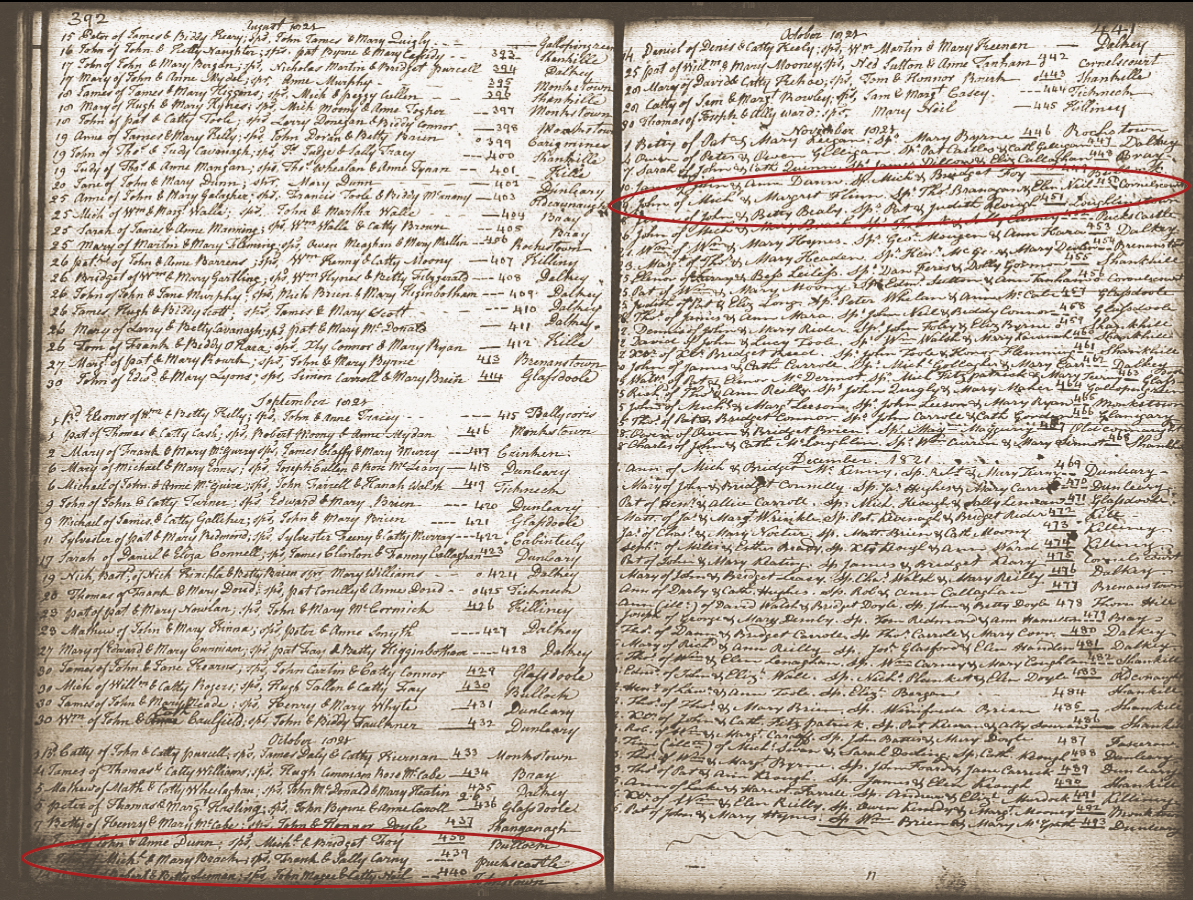

As I searched for a christening record for John Brack, son of Anthony Brack and Rose Smyth, I discovered an oddity. There is no record for him, however, there are two christening records for a John Brack born at Puck’s Castle, son of Michael and Mary Brack. The records sit on opposing pages of the same book, dated a month apart, one 12 October and the other 16 November 1822. Both have the same witnesses, Frank and Sally Carney.11

What does this mean? I had theorized that John was a sickly baby and was baptized a second time, his parents hoping for a miracle. I had heard that was not an uncommon practice. I assumed that if that were the case, the baby had just died. (Oh, ye of little faith!)

On the other hand, these two records may represent the two different John Bracks, one recorded inaccurately. I imagine the priest scribbling notes to himself as he performs the ordinance, then later recreating and recording the information in his record book. When it came to the two Johns, he recorded the same parent and sponsor information for both John Bracks. Whoops! Honestly, I can see it happening. Aren’t we all confused by the plethora of John Bracks!

In any case, we know there was another John Brack in the area. When I found that piece of the puzzle under the couch, I discovered others hiding there with it; they all began to make more sense. In 1862, John Brack and Catherine Brack of Shankill gave birth to Anthony Brack who was christened at Ballybrack Parish on 23 February.12

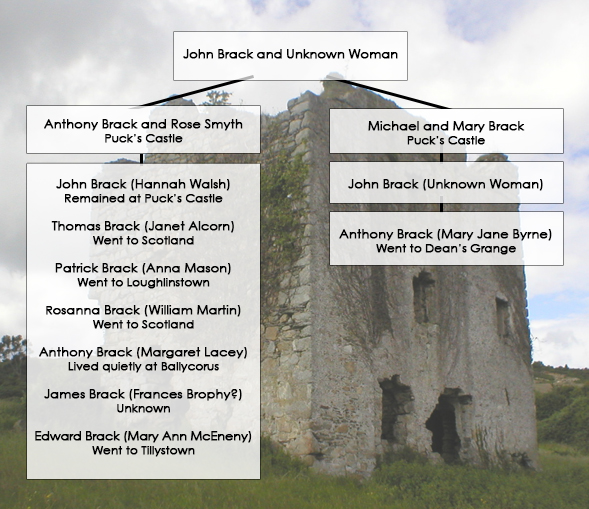

Putting all of these puzzle pieces together, a picture begins to emerge that makes sense, although it is more complicated than what I originally supposed. Here is our current working theory:

- Anthony Brack of Dean’s Grange is the son of John Brack, who is the son of Michael and Mary Brack of Puck’s Castle.

- John Brack was born October or November 1822 while his family resided at Puck’s Castle. The fact that Michael and Anthony both named their sons “John” (and that Michael and Mary were also living at Puck’s Castle) strongly suggests the two men were brothers and each named his son after their father, John Brack.

- John, son of Michael, married “Catherine” and was living at Ballycorus when Anthony was born in 1862. After Anthony and Mary Jane returned from England, their daughter Mary was born at Tillystown, which is in Shankill. Tillystown was created by Benjamin Tilly as a place where Lord Domville’s tenants could live after he kicked them off his land. (We have no evidence that these Bracks were tenants of Lord Domville, although the Bracks at Puck’s Castle were but refused to leave their tenancy.) By 1889 Anthony Brack, his father John, and his growing family had all apparently relocated to Dean’s Grange. That’s where Hannah Brack was born and where Anthony was subsequently found with his wife and children.

Although this theory of origin makes sense, it’s important to remember that parts are still unproven. Did John and Michael of Puck’s Castle have the same father and was he named John? In testimony before the Cabinteely Voter Revision Sessions in 1894, John of Puck’s Castle insisted that his grandfather had lived in the same house John resided in, the stone house near the Ballycorus smelter tower.13 But we have no documentation showing the grandfather’s name was John, although naming patterns strongly suggest he was. Likewise we cannot confirm that John and Michael were brothers.

It’s important not to get too attached to theories; it’s better to keep looking for forgotten puzzle pieces under the couch!

NOTES

1. There are 106 documents on FindMyPast that relate to “Anthony Brack,” which include christenings, births, deaths, marriages, land records, court sessions, prison records, workhouse records, but doesn’t include newspaper articles. Some documents have Anthony Brack mentioned but the document is regarding someone else, i.e., a child’s christening record. Eight documents relate to the families at Puck’s Castle; 33 to the group at Dean’s Grange; 30 to Anthony, the son of Patrick; the others are miscellaneous or were not able to be reliably assigned to a group.

2. A jennet is a female donkey.

3. Irish Prison Registers 1790-1924, Mountjoy, Dublin, Ireland, Anthony Brack, Prisoner #3466, Admitted 25 August 1910.

4. “Stealing Sod,” 1 February 1908, Wicklow People.

5. “Sand from Brighton Bay,” 23 April 1910, Wicklow People.

6. Anthony Brack is hired to deliver sea gravel: Poor law records of Rathdown Poor Law Union, 1841-1921, Guardians Minute Book, dates:31 Dec 1890; 25 November 1891. He is called as a witness in a coat theft: Sergeant Casey accused Edward Ryland of borrowing a coat and not returning it. The Court determined the owner had lost the coat. Anthony Brack was a witness for the prosecution. Evidently he wasn’t very convincing! Ireland, Petty Sessions Court Registers, Cabinteely, 25 Nov 1891.

7. On 10 August 1914, James Brack (using the name Thomas) began serving time at Mountjoy for breaking and entering and larceny (a catch-all term for theft). He was released early as a first offender, but was back again on 15 November 1915 for assaulting John O’Connor. On 9 July 1915, John Brack began serving a sentence for larceny (Records located in Mountjoy Prison General Register, Male, 1913-1916, Book no 1/45/2, Item 2).

8. Marriage of Ellen Mooney and Anthony Brack, 12 August 1932,

County Dublin. Leo Macken and Margaret Byrne were witnesses. (Group Reg ID 1411064, Ireland, Civil Registration Indexes 1845–1958, General Register Office, Republic of Ireland. “Quarterly Returns of Marriages in Ireland with Index to Marriages”).

9. “Bagging Sand,” 2 March 1890, from Freeman Journal.

10. Puck’s Castle was at various times called Ballycorus, Rathmichael, or Shankill. Ballycorus referred to the nearby mines and smelter; Rathmichael was the Catholic parish Puck’s Castle was located in. Shankill in those days referred to part of the lands which Lord Domville controlled; Puck’s Castle was part of them.

11. “John of Mich’l and Mary Brack; sp’s Frank and Sally Carny Puckscastle.” John Brack of Kingstown parish, residing at Puck’s Castle, dates 12 October and 16 November, 1822. (Catholic Parish Registers, National Library of Ireland, Ireland. Found on registers.nli.ie).

12. John Brack’s christening information was found through RootsIreland. The original document is not found in the NLI collection, but the transcription was done by the Dun Laoghaire Historical Society. Sponsors were Thomas Cassidy and Eliza Walker.

13. John Brack testified, “his father and his grandfather were in the house that he was in before him and they had votes,” (11 September 1894, Irish Daily Independent, Dublin, Ireland). This statement was an attempt to claim voting rights; the latter part of his statement is false, but the first half, that his grandfather lived in the house, may very well be true.