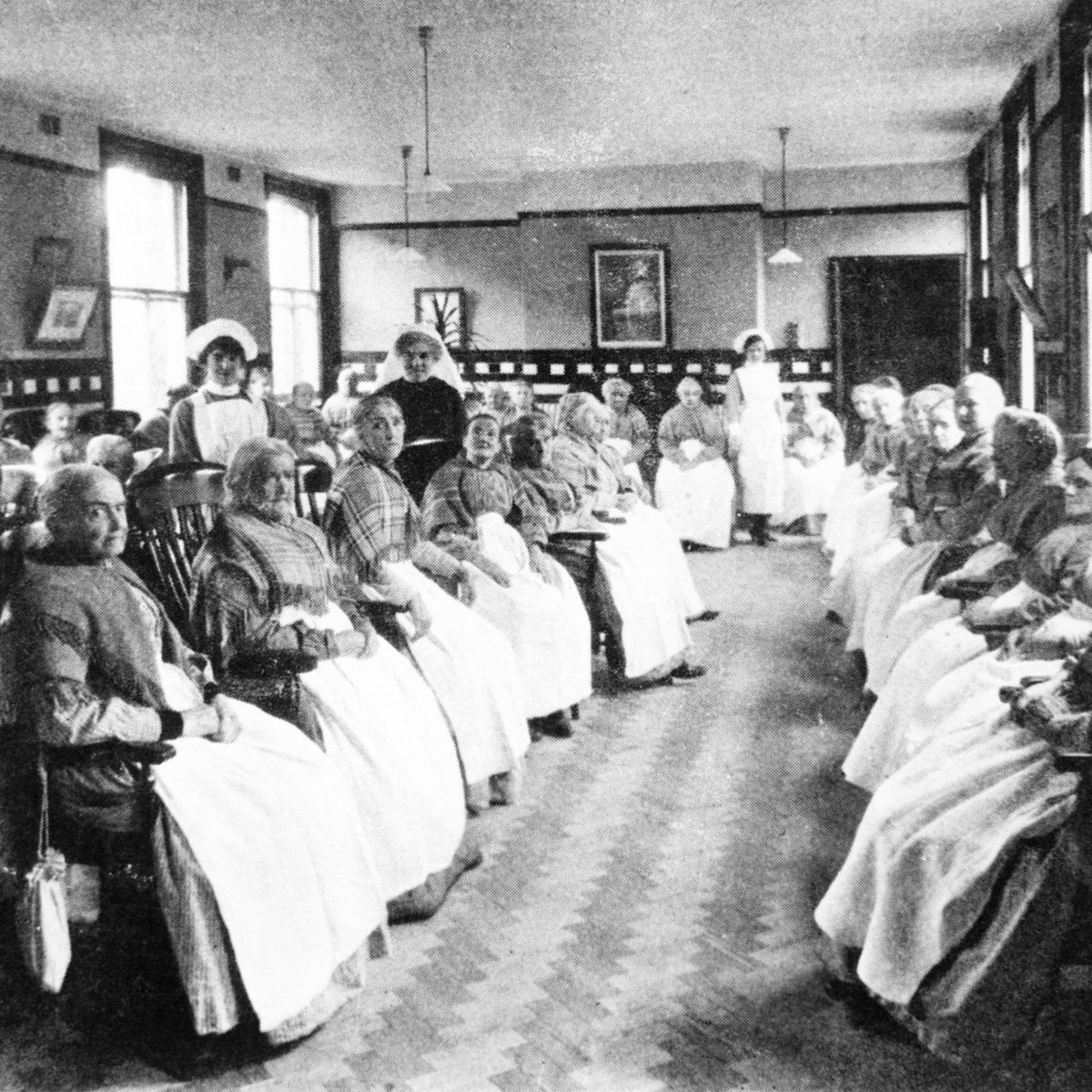

On a certain Sunday, I formed one of the congregation assembled in the chapel of a large metropolitan Workhouse. With the exception of the clergyman and clerk, and a very few officials, there were none but paupers present. The children sat in the galleries; the women in the body of the chapel, and in one of the side aisles; the men in the remaining aisle….

The usual supplications were offered, with more than the usual significancy in such a place, for the fatherless children and widows, for all sick persons and young children, for all that were desolate and oppressed, for the comforting and helping of the weak-hearted, for the raising-up of them that had fallen; for all that were in danger, necessity, and tribulation. The prayers of the congregation were desired “for several persons in the various wards dangerously ill;” and others who were recovering returned their thanks to Heaven.

Among this congregation, were some evil-looking young women, and beetle-browed young men; but not many—perhaps that kind of characters kept away. Generally, the faces (those of the children excepted) were depressed and subdued, and wanted colour. Aged people were there, in every variety. Mumbling, blear-eyed, spectacled, stupid, deaf, lame; vacantly winking in the gleams of sun that now and then crept in through the open doors from the paved yard; shading their listening ears, or blinking eyes with their withered hands; poring over their books, leering at nothing, going to sleep, crouching and drooping in corners.

There were weird old women, all skeleton within, all bonnet and cloak without, continually wiping their eyes with dirty dusters of pocket-handkerchiefs, and there were ugly old crones, both male and female, with a ghastly kind of contentment upon them which was not at all comforting to see. Upon the whole, it was the dragon, Pauperism, in a very weak and impotent condition: toothless, fangless, drawing his breath heavily enough, and hardly worth chaining up.

(Charles Dickens, “A Walk in a Workhouse,” Household Words, Volume I, Magazine No. 9, 25 May 1850, pp. 204-207.)

Who was Margaret Martin? What did she look like? What things mattered to her?

We know when Margaret was born and when she died. We know who her parents were and that she had four sons. We know she was born in Scotland but lived most of her life in Ireland. And we know that at 40 years old she was 5’3″, had brown hair, a sallow complexion, and weighed 148 pounds.1

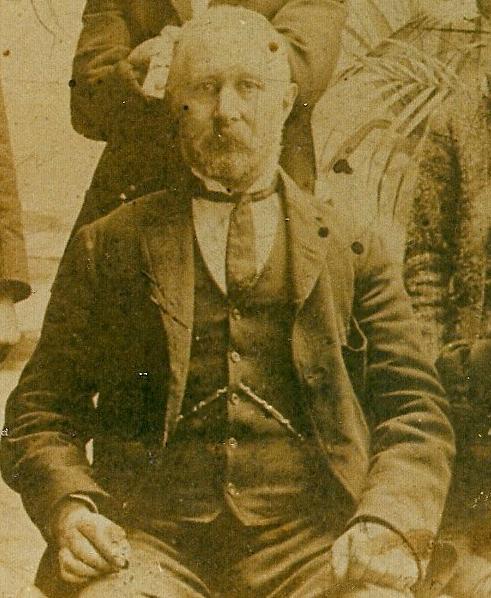

Sadly, that doesn’t give much of a picture, does it? But examine the photographs in the image at the top of this post—you can see a marvelous thing. In the eyes of Margaret’s two sons, her brother, and her female cousin, there is a likeness. The chin and the cheekbones—there is a commonality among them. Almost we catch a glimpse of what Margaret may have looked like. What we cannot see we can imagine.

Now if Margaret had learned to read and write, she might have been able to keep a record and tell us things of her heart. She could not and did not. But we can still come to know her—we can search for Margaret by studying the information we have, by learning of the lifestyles, people, and customs of her time and place. We may not know every detail, but we can piece together a glimpse, an informed picture of what Margaret’s life was like.

Margaret’s Beginnings in Scotland

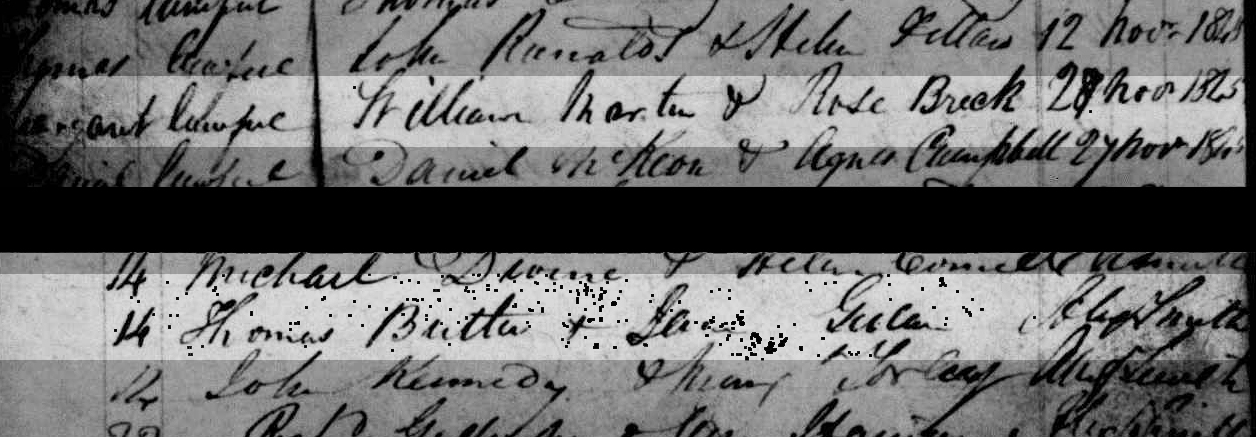

Margaret Martin was born on November 24, 1845 to William and Rosanna Brack Martin, and she was christened on December 14, 1845 at St. Margaret’s Church in Airdrie, Scotland. The sponsors (or godparents) were Thomas Butler and Jane Gulan. Margaret joined a family that had already been blessed with two boys—Peter (1839) and William (1844)—and a girl, Elizabeth (1841).

Margaret’s family were Catholic and each of the girls in the family were christened at St. Margaret’s Catholic Church, but no christening records have been found for Peter and William, not at St. Margaret’s nor anywhere else in Scotland or Ireland.2

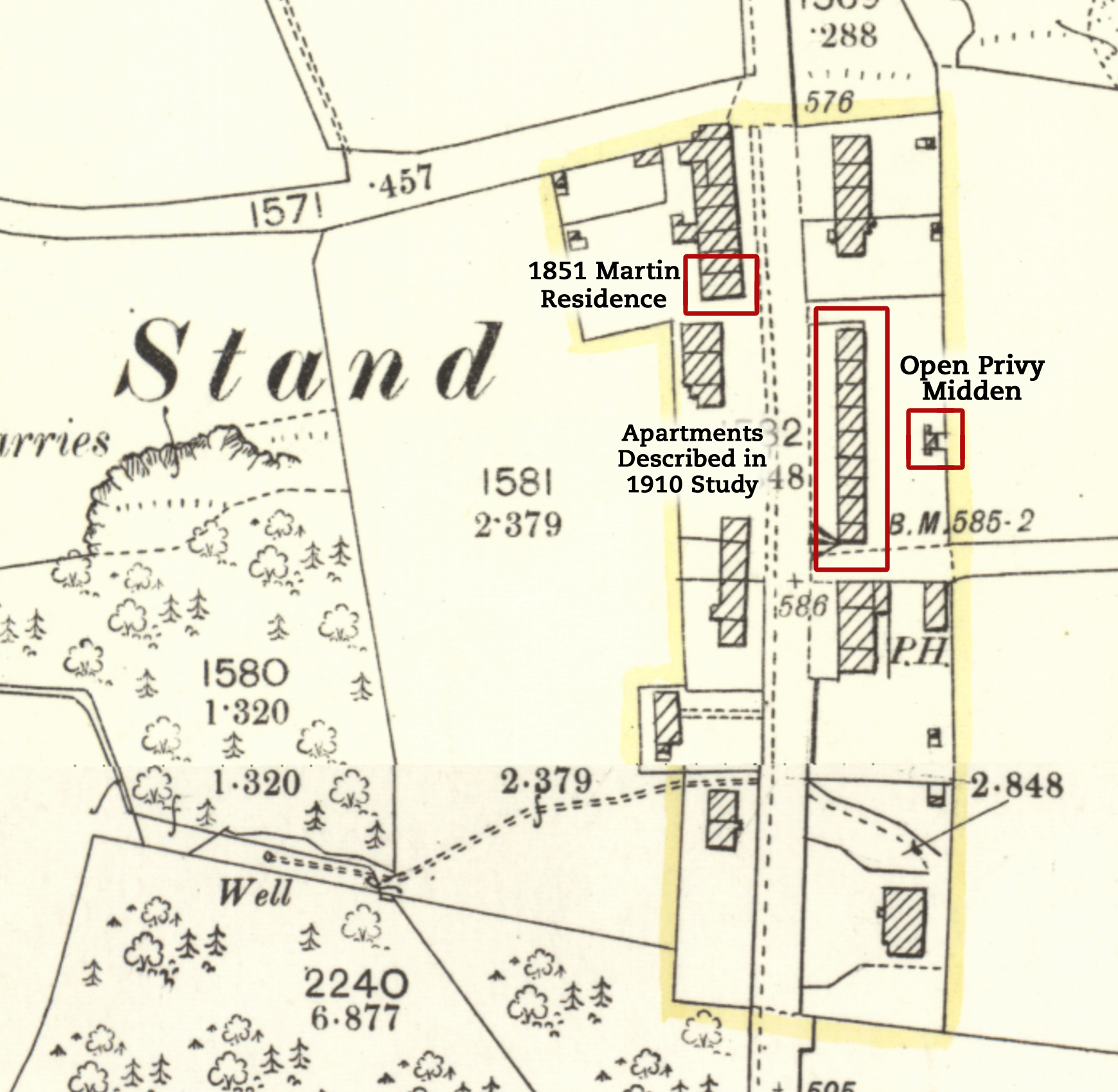

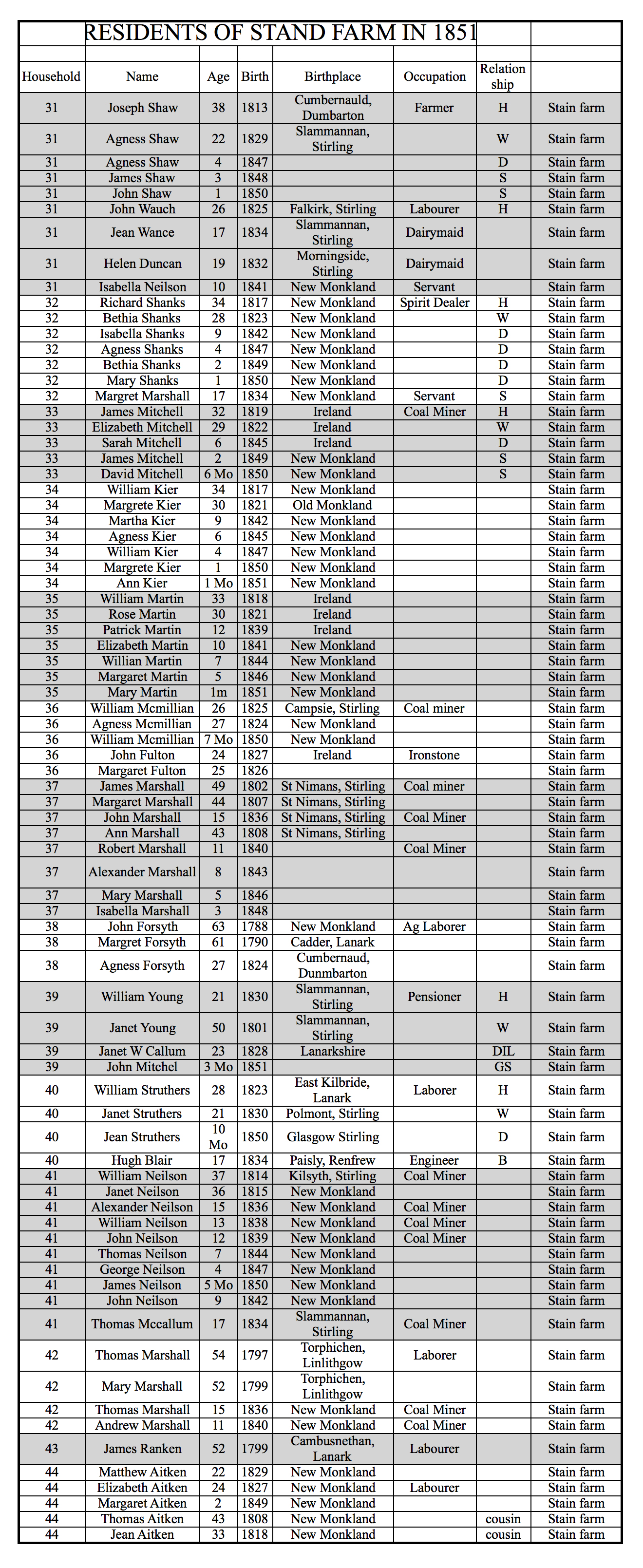

Margaret’s first memories would have been shaped in a miner’s row house in the hamlet of Stand, north of Airdrie, Scotland. The Martin home contained two rooms with two windows in a 25′ x 25′ stone building. The house was drafty, and very likely Margaret slept in the same bed with her two older brothers and sister for warmth. Stand consisted of a half-dozen clusters of row houses, a handful of cottages, a farm, a disused quarry, and Rochsoles Pit #4—an ironstone and coal mine.3

In 1910, Scotland’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr John T. Wilson, undertook a survey of the quality of miner’s housing. He included in his study nine one-apartment houses at Stand. These homes appear to be a section of housing across Stirling Road from where the Martins lived. Although the report doesn’t describe the Martin’s home, it gives insight into what the neighborhood housing conditions were like. According to Wilson’s report, the houses were one story and built of stone with wooden floors. The internal walls and ceiling were not finished, but simply rough and broken stone. The household water was hauled from a “standpipe” or spigot at the end of the row.

Hygiene had its limitations. There was an “open privy midden”—essentially an outhouse—centered at the rear of the row of houses with a trash collection area. All tenants used this facility that was “scavenged” weekly. The units had no sinks or washhouses and no coal cellar. On the other hand, the rooms were considered large, and garden ground was available (although at the time of the report, none was being cultivated). In 1910 the units rented for £2 12s, although it is not clear if that indicates the monthly or annual amount. Following the housing report and after negotiations, these houses were demolished.4

Note on Fig. 3 that each group of row houses had a small building at the rear. This was most likely a “privy midden” and trash collection center, similar to that of the nine surveyed units. The Martins and their neighbors all relied on outdoor toilet facilities.

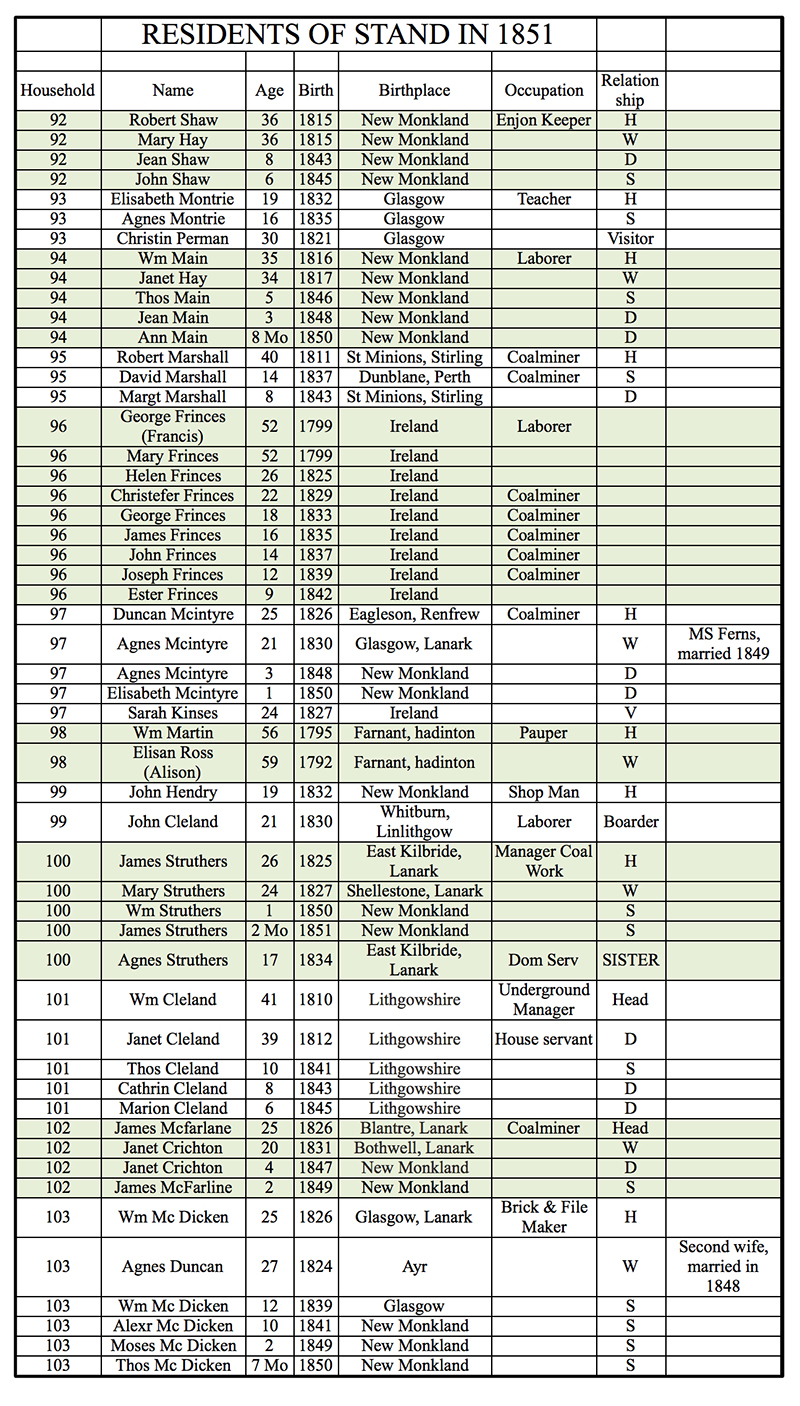

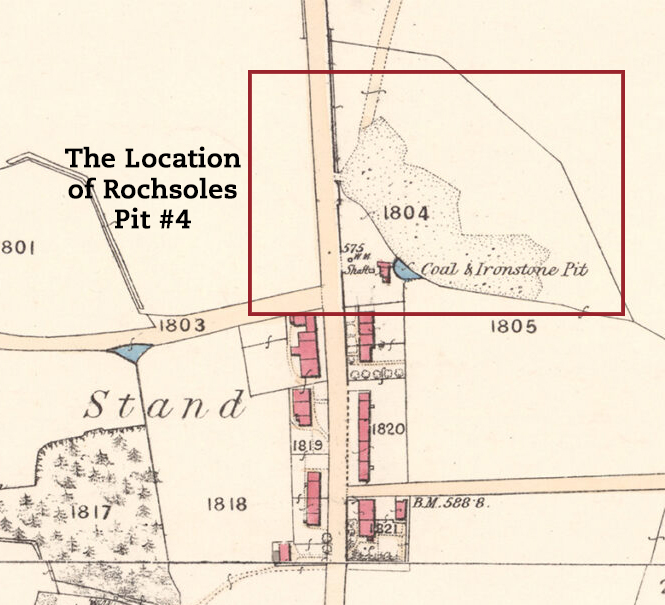

The 1851 Census of Stand Residents

In the 1851 Census, Stand boasted 130 residents living in 26 homes—all were born in Scotland save 17 who claimed Ireland as the land of their nativity. William, Rosanna, and “Patrick” (Peter) Martin were three of the 17 born in Ireland. More than half of the residents were under 18—70 of the 130 people living in Stand were children or babies. Many of the children were listed as “scholars” and probably attended school together, although nine male children (under 18) were listed as miners.5

Of the 34 adult males, 20 were listed with an occupation related to mining, while the other men were farm workers, ordinary laborers, or retired (as were several of the women). The community was also blessed with Miss Montrie, a 19-year-old teacher, and Mr. Shanks, a “spirit dealer.” (Presumably he sold liquor as opposed to holding séances.)

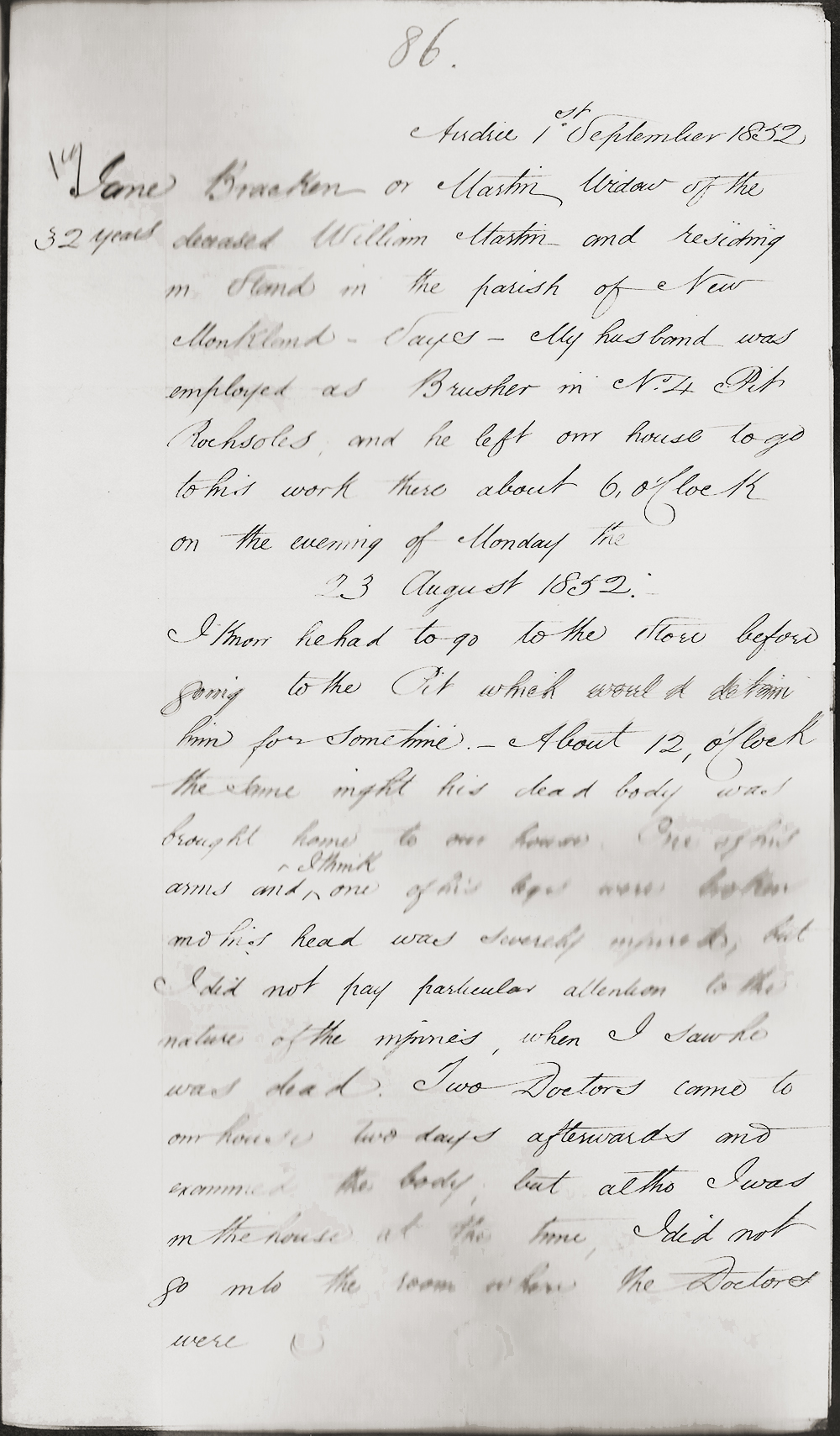

William Martin had brought his family to Ireland to take advantage of the plentiful work the area offered. He was an ironstone miner, an occupation that took great strength and resilience. He worked hundreds of feet below ground, in a tunnel only as wide as he was. He would lie on his side while swinging a pick to loosen ironstone ore. We know that William worked at Rochsoles Pit #4 from records surrounding his death. 6

There were numerous coal pits being worked on the Rochsoles estate, but we believe William worked at the pit nearest home that was just north of Stand. Testimony from the Rowatt trial indicates Rochsoles Pit #4 had mining tunnels at two levels, one accessing a seam of coal and the other a combined seam of coal and ironstone. The pit just north of Stand fits the description for Pit #4—it is the only one labeled on ordnance maps as mining both coal and ironstone. William had identified himself as an ironstone miner on the 1851 Census, but trial testimony says that at the time of his death he was working on a coal seam. Evidently the mining company had ceased working the ironstone seam the previous year, and William had changed jobs and probably shifts. William became a “brusher,” a job usually done at night when the other miners had gone home. The brushers removed excess rock from the tops of the underground tunnels so that the tunnel height would meet regulations and so that no loose rock would fall and injure the workers.

The dangers of mining were plenty, with gas seeping through tunnels, water flooding the works, rockfalls, and years of inhaled dust congesting the lungs. While mining provided William and others with the means to keep their families alive, it also took men away from their families at too young of an age. Margaret was only six when William was killed in an accident at the mine merely yards from their home.

On August 23, 1852, Rosanna reports that William left several hours early for his night shift at the mine to make a trip to the store. He may have needed to sharpen tools or perhaps wanted to have a drink with his friends before his work began, but why leave so early? The answer may lie in an 1871 complaint against the Rochsoles Coal and Oil company by a miner named Mullins. He reported the following: “The smithy is about a mile away from the work, and during the first five or six mouths I was there I paid a boy 6d. a fortnight for carrying my picks to get sharpened. That was 1s. a fortnight I had to pay for the smithy. . . . You must either send your picks all that distance to the smithy or take them to another smithy to be sharpened, and if you take them to another then you have to pay for that in addition to paying the smithy off-take.” It’s quite likely that was the case with William, that the smithy was located at a distance and he had to walk there or pay extra to sharpen his tools elsewhere.7

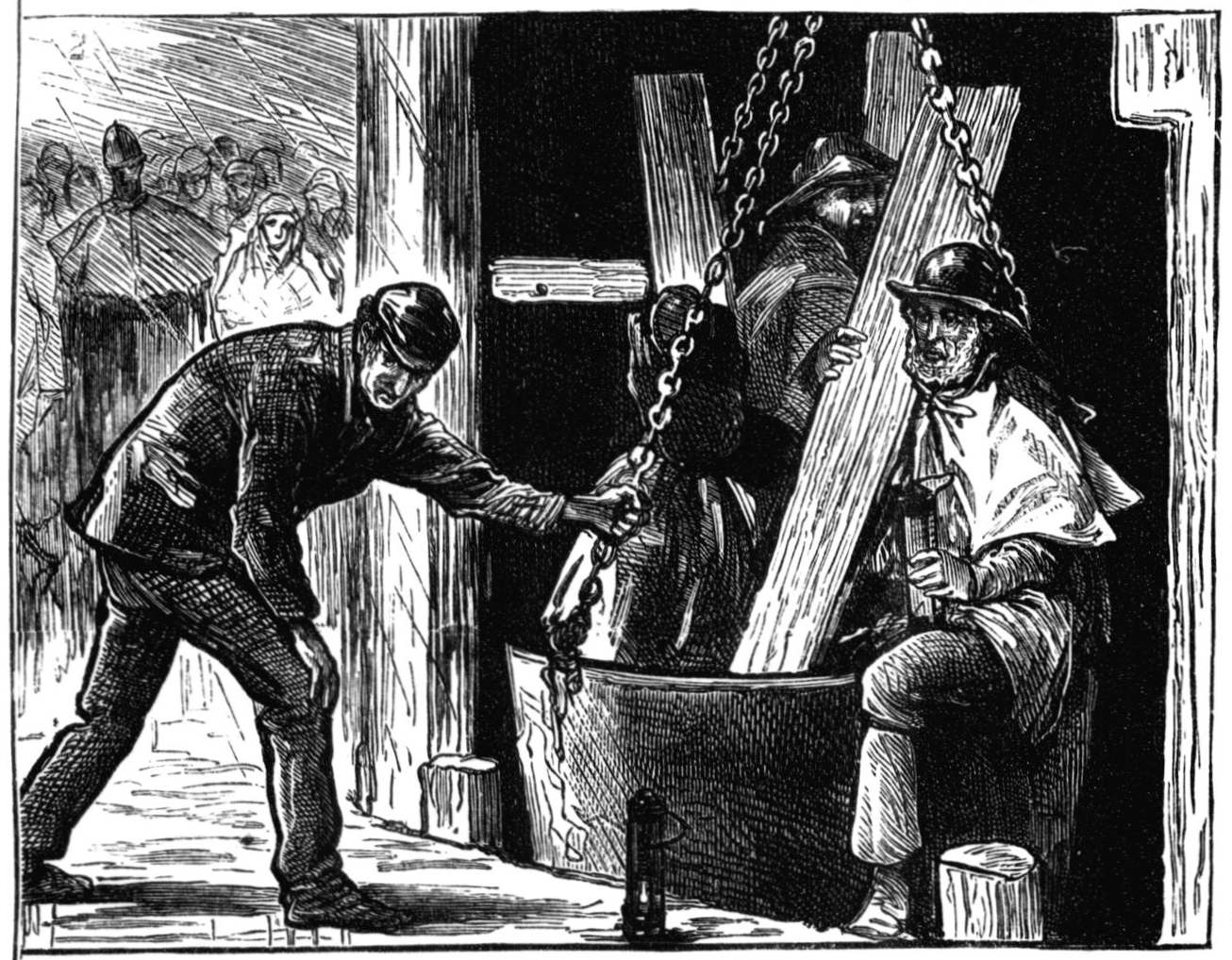

William arrived at the mine at 8:45 p.m., just as the summer sun was setting. Robert Rowatt, the engineer, was using the steam engine to pump water out of the mine, so William waited a few minutes until Rowatt switched the drive gears over to running the cage lift.

Once the gears were switched over, William entered the cage with Thomas M’Lachlan and James Marshall, his coworkers who were also his neighbors at Stand. Among the three of them they carried several picks, wood, and other tools. Once the men were aboard the cage lift, the “down” signal was given, and the cage began to descend—then it abruptly fell to the bottom of the mine shaft. The engineer had not followed the safety protocols that specified tightening the nuts and bolts with a tool and inserting a “key” or pin to make sure the gears stayed meshed together. Consequently the gears separated under the weight of the laden cage, and William fell to his death. The other two men survived the fall but sustained devastating injuries to their legs and feet.

RELATED CONTENT—”William Martin, Death of a Scottish Miner”

William’s body was brought to the surface where he died. He was carried back to his home in a cart, arriving at about midnight. His body would lie there in state in one of the family’s two rooms for several days. On the third day after William’s death, two doctors came to perform an official examination for the upcoming trial. William had suffered a broken arm and leg as well as severe head and internal injuries. William was probably then buried in an unmarked grave.8

We don’t really know what happened to the family after William died. Although the row house where the Martins lived does not appear to have been owned by the mining company, without the income William provided, the family could not pay the rent to stay in their home. Rosanna may have been able to find work at the mine although she had one-year-old Mary to care for and very likely was carrying another child that would be born the following January.9 Peter was 13 years old and could and probably did work full time in the mine although not with the same income that his father would have made as a full-grown, experienced miner. Elizabeth was old enough to work as a live-in servant, to earn her board and keep and perhaps a bit more. William was too young to work in the mines under the 1842 Mines and Colliery Act—although that doesn’t mean that he didn’t. Mining inspectors often looked the other way when mine owners needed child labor to stay profitable, and children often lied about their ages in order to work to keep their family from starvation.10

Rosanna gave birth to Edward on January 2, 1853,11 but after the christening they both disappear, possibly dying from complications of the birth or pregnancy. Scotland began keeping statutory records of births, deaths, and marriages in 1855, but neither Rosanna nor the child Edward appear in them, nor do they appear in the 1861 Census. Based on these facts, we believe Rosanna and Edward died in 1853 or 1854. By 1855 the evidence suggests the Martin children were orphaned.

What happened between Rosanna’s death and 1861 is a mystery, however, the 1861 Census shows the Martin children living in various places across Scotland in a settled lifestyle. Peter and William were ironstone miners in Dalry, Ayrshire. They boarded with the Lafferty family, and both boys claimed to be two years older than they actually were.12 Elizabeth worked as a live-in servant with the Rankin family at 461 St. Vincent Street in Anderston, a neighborhood of Glasgow.13 Mary lived on Tower Street in Portobello near Edinburgh, with her mother’s brother, Thomas Brock. Uncle Thomas and Aunt Jesse were childless and were likely quite happy to take in their young niece.14

Margaret is the only one who doesn’t appear in the 1861 Scotland Census. After much searching we discovered that she had been sent back to Ireland, presumably to live with family there.

Margaret in Ireland

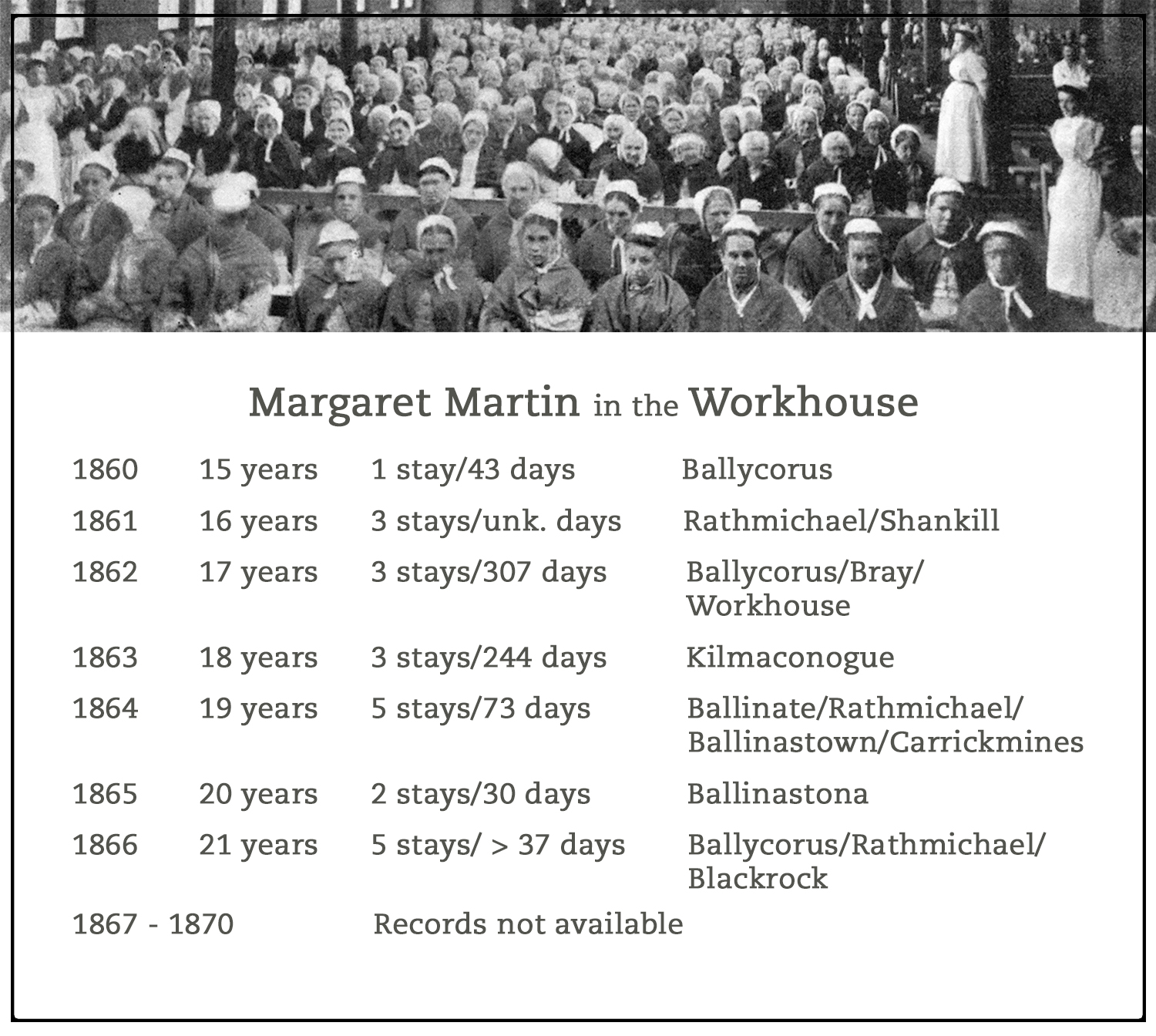

We don’t know exactly when Margaret arrived in Ireland. Being only seven years old when her father died, Margaret would certainly have needed someone to look after her. But whatever hardships and sorrows she may have experienced are lost to history. The first record we find for Margaret Martin was created on June 25, 1860 in the Rathdown Workhouse at Loughlinstown, County Dublin, Ireland. On this occasion sixteen-year-old Margaret lived in the workhouse for 43 days until August 7, 1860.15

The workhouse intake roll indicates Margaret Martin was healthy, although dirty, and her usual residence was at “Ballycorus,” a community built up to house workers and manufacturing works for the Ballycorus mine and smelter. By this time Ballycorus had attained a respectable size: 11 workers’ cottages, a manager’s house, two furnace houses, a silver refinery, rolling and pipe mills, a shot tower, and storage bunkers.16

Where was Margaret before that 1860 workhouse stay? It’s possible that she lived with Martin relatives although we have no information of Martin family living in the area. We do know Margaret had lots of Brack family in County Dublin in the mid 1800s. Uncle Anthony and Aunt Margaret Lacey Brack lived in Ballycorus at times, although they also lived at Sandyford and elsewhere. Patrick Brack and Ann Mason lived in Loughlinstown although he probably worked at Ballycorus. Edward and Mary Ann MacEneny Brack lived in Ballycorus at least until 1874, and Edward also worked at the Ballycorus smelter. They later moved to Tillystown.17

However, excepting Anthony Brack who married Margaret Lacey in 1854, none of Margaret’s uncles had married by 1855 when we suspect she came to Ireland. It seems most likely that young Margaret lived with her grandparents at Puck’s Castle, especially before 1860. The Puck’s Castle area was often referred to as part of Ballycorus, being only a mile from the smelter itself.

The Brack House

Anthony and Rose Brack, Margaret’s grandparents, lived at Puck’s Castle at the foot of the Ballycorus Smelter Tower. Their farm lay surrounded by green hills with a sweeping ocean view—that would have been a huge contrast to what Margaret had known in Scotland. In those days Scotland’s ever-present smelter smoke and heavy rain-laden skies made everything feel dark and dank.

RELATED CONTENT—”A Study: Anthony Brack and His House at Puck’s Castle”

The Brack house was a small, sturdily built stone house on a rocky mountain hillside. Erected sometime before 1836, the stones that formed the walls of the cottage came from the Brack’s own ground, dug out in an attempt to make the fields more arable. Anthony and his sons placed the stones themselves, an accomplishment that would stand and house Bracks for nearly 170 years and as many as six generations.18

There were two rooms with an open fireplace in one room that exhausted through a chimney in the roof. There were two windows, one each per room, and the square footage of the two rooms combined measured no more than about 200 square feet. The roof was probably thatched at that time, although corrugated iron was later placed over the thatch.19

In the early 1860s, the Brack house still gave shelter to Anthony (and Rose Brack if she was still alive); John and Hannah (Walsh) Brack and their young and growing family also lived there. John Brack worked as a carter, probably hauling ore from the mines to the smelter in a horse-driven cart, much like his father had. By 1862, railway tracks were laid and a station built that allowed ore to be sent as far as Shankill before being carted by horse to the smelter. Before 1862, all ore was hauled by cart from the lead mines in Glenmalure, an arduous trip.

Margaret and the Workhouse

If Margaret had family nearby, why did she stay at the workhouse? We don’t really know. She apparently worked as a servant part of the time, and perhaps she valued her independence and didn’t want to go back and live with family—and perhaps there wasn’t enough food to go around in the Brack household. In one sense we are fortunate Margaret did choose the workhouse—most of what we know about her during the 1860s is derived from workhouse records.

In 1861, Margaret entered the workhouse on three occasions: July 24, 1861; October 13, 1861; and October 29, 1861. There is no length of stay recorded for these visits, and she lists a different usual residence on each occasion: Rathmichael, Shankill, and Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire). These may have been locations where she had found work as a live-in servant between workhouse stays.

In 1862, Margaret spent so much time in the workhouse that her residence was listed as the workhouse. Her first stay began February 4, 1862, and lasted nine days; her residence once again was listed as Ballycorus, but her occupation was listed as a “flax dresser.” Flax dressers used a hackle to separate the coarse bits of flax so it could be spun and woven into linen. Linen was one of Ireland’s greatest exports, and much of the processing work was done by women in their homes. It’s not surprising that Margaret may have tried her hand at it.

From February 13, 1862, until June of the following year, Margaret appears to have lived at the workhouse nearly continually. She gave her residence during this time as “Bray,” and her occupation again became “servant.”

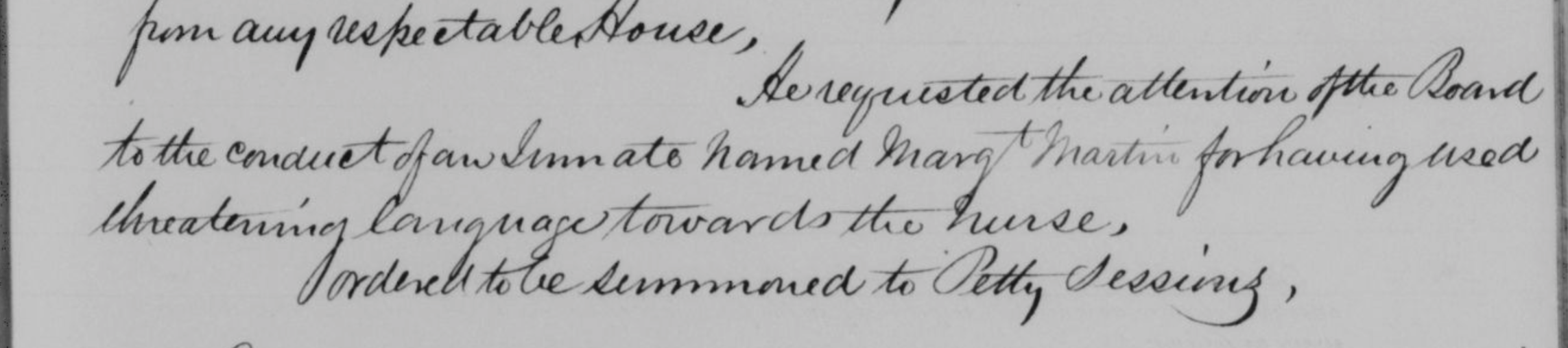

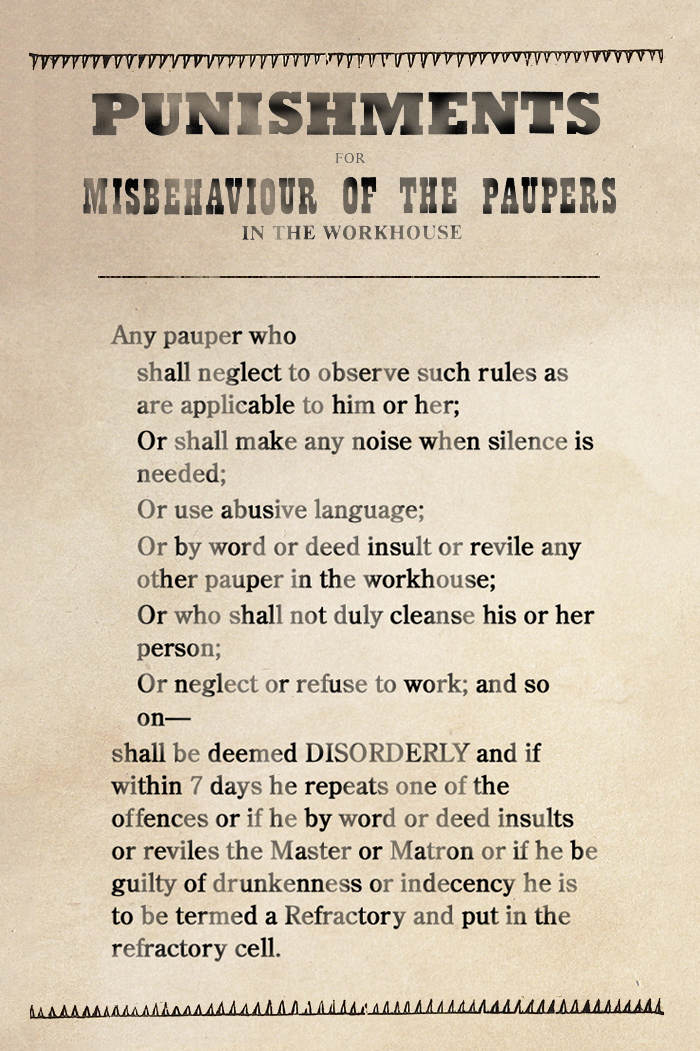

During this extended stay, Margaret may have run into some trouble with the workhouse staff. At an August 13, 1862 meeting of the Board of Guardians, the Master “requested the attention of the Board to the conduct of an inmate named Marg’t Martin for having used threatening language towards the nurse.” 22 She was ordered to be summoned to the Petty Sessions, a court for minor offenses. Although there is no record of any court deliberations nor of a stay at Grangegorman’s Women’s Prison, there’s a gap in Margaret’s residence at the workhouse from August 19 to September 3, 1862, that could be explained by a short prison sentence. Margaret would be disciplined for workhouse misbehavior on at least four other occasions.

Margaret stayed in the workhouse for most of the first half of 1863. An eight-day stay in July and an extended stay of more than three months that began September 3 added up to 244 days at the workhouse for Margaret in 1863. In 1864, she had five stays that averaged to about 14 days each, for a total of 73 days for the year. 1865 was her best year yet, with only two stays in April and May that totaled 30 days in the workhouse. By this time Margaret was 20 years old; her 1864-65 residences were given as variations of “Ballinastoe,” a townland in the Rathdown Union that I haven’t been able to locate.

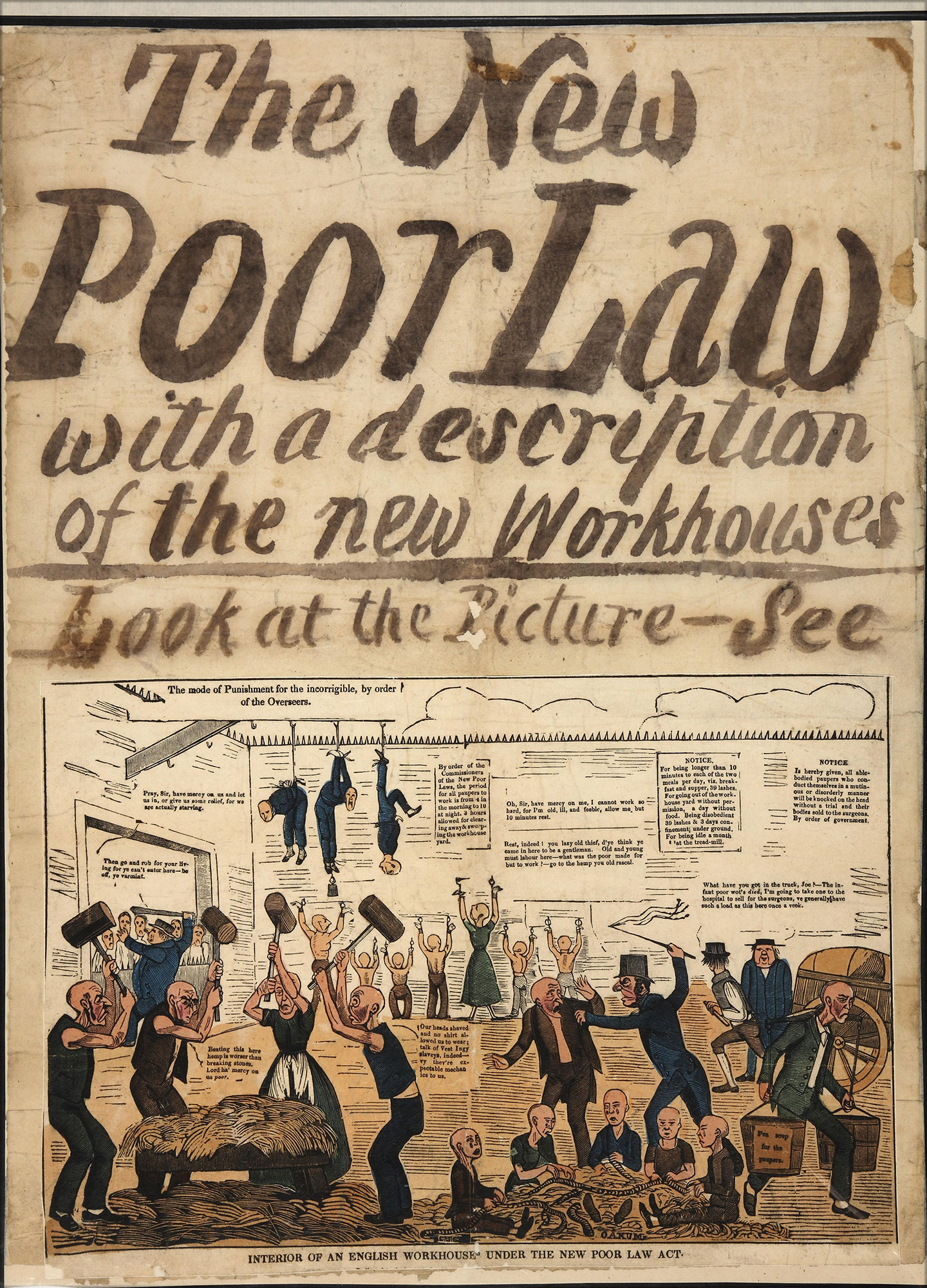

The Workhouse Solution

Life in the workhouse intentionally lacked abundance or comforts. Small quantities of poor-quality food, separation from loved ones, forced labor, and meager accommodations were intended to discourage all but the truly desperate from entering the workhouse, and to encourage those who did enter to not stay any longer than absolutely necessary.

This concept of how to help the poor was developed by Edwin Chadwick in England in 1834. Previous efforts had relied on giving those in need an allowance which, it was felt, “completely degraded the labourers and spoiled the labour market,” says Malachy Powell in a paper read to the Graduates Club in 1965.23 Chadwick’s solution was to build workhouses for the poor so that “the pauper would work for the Parish but he would do so under conditions that he would accept only if he were destitute. He would work in the workhouse—a well regulated workhouse, a place of strict discipline, sex–segregation and low diet—so that his condition would be ‘less eligible’ than that of the independent labourer of the lowest class. The workhouse, according to Chadwick, was the great filter and the ‘workhouse test’ attained the status of an exact formula. This test was held to be a self–adjusting and foolproof device to sift the deserving from the non-deserving. If he did accept the spider–like invitation, he accepted such poor conditions that it prove the truth of his claim that he was really destitute. This was the workhouse test.”24

Powell explains the flaw in Sir Chadwick’s thinking: “The workhouse solution even in England was founded on a mistaken assumption. The whole fallacy about the work of scheme was that work was obtainable and that there was a free labour market into which the indolent worker could be forced by the workhouse test. But however true this was in some parts of England it was not at all applicable to Ireland, where however industriously inclined the population was, there was just no work to be had.”25

Because so many Irish were immigrating to England and taxing the welfare support systems there, pressure mounted to find a solution for Ireland. A Royal Commission was appointed and a study ensued that eventually recommended other options besides the workhouse, which did not seem to be a good fit for Ireland. But the British authorities were impatient for something to be done, so another expert was called upon, George Nicholls, an advocate of the workhouse system. Nicholls visited Ireland and decided that workhouses would be just the thing. The one drawback he saw was that “to carry out the principle of the workhouse system to its full extent it was necessary for workhouse inmates to be worse clothed, worse lodged and worse fed then the independent labourers of the district. He said that the difficulty was that it would be impossible to make the lodging, clothing and diet of the inmates of an Irish workhouse inferior to those of the Irish peasantry. The standard of the peasantry was so low the establishment of a lower standard was difficult and he thought even inexpedient.”26

Queen Victoria signed the Workhouse Bill on July 31, 1838, and construction immediately began on more than 100 workhouses across Ireland, overseen by George Nicholls. Once they were built, a Board of Guardians was appointed to administer and regulate each workhouse.

Life in the Workhouse

A typical entrant into the workhouse could expect efficient if uncompassionate treatment when he or she entered its doors. Workhouse inmates had to be approved by the overseer before they could be admitted, and new inmates were required to strip off their clothes and bathe. The condition of many incoming residents was marked as “Dirty,” so bathing would have been important—unfortunately, a large group would bathe from the same draw of water, so unless a person was one of the first in, the results could not have been satisfactory. Next inmates were given a workhouse uniform to wear while their clothes were fumigated and stored for when they left. Men wore a cap, shirt, jacket, shoes and trousers of grey frieze or corduroy. Margaret would have worn a gown with a petticoat, shift, apron, cap and shoes. Workhouse clothing was required to be worn at all times.26 The clothing was plain and made of coarse, sturdy fabric, however, it was often in better condition that which the pauper arrived in. For that reason, inmates who left and took the clothing with them were charged for theft.

Next the inmates were divided into different groups: men and women, adults and children, healthy and sick. Healthy adults were expected to work. Children attended school. The sick were sent to the hospital where they were further separated into groups of Catholic and Protestant adherents.

Each day started early at 6:00 a.m. when a bell rang to raise the paupers from their beds. Roll call was taken, the inmates were inspected for cleanliness, and a prayer was said. Then the inmates lined up with their cups and plates for the morning rations, a meager breakfast of stale bread or Stirabout, a watery gruel. Regulations stated that a workhouse breakfast should consist of 8 oz. of stirabout and 1/2 pint of milk, and dinner should be 3 1/2 pounds of potatoes and a pint of skimmed milk. Often the rules were not enforced and masters freely cut corners to make the food “go further.”28

After breakfast, the adults were sent to work and the children to school. The children at the Rathdown Workhouse were taught reading, writing, and arithmetic for three hours each day. Some were also taught to play musical instruments, which must have been a bright spot in the children’s otherwise dreary existence. The school band was called upon to perform on special occasions.

The work given the inmates could be very arduous. Men could be asked to break up stones, grind bones, work in the fields and in the kitchen and do maintenance around the workhouse. Women might be employed in sewing uniforms, spinning, nursing sick inmates, cleaning, and other chores needed to keep the workhouse running. There are reports that inmates were assigned to the treadmill in the South Dublin Workhouse, but that may not have been the case at Rathdown.29

At 6:00 p.m. the bell sounded, which signaled dinnertime. The potatoes for each person were put in a net and weighed, then they were boiled still in the nets. The boiled potatoes were put on trays and carried to the dining hall. In some workhouses the paupers had wooden or tin platters for their potatoes; in others they ate them off the table. The nets were collected, grace was said, and the meal was eaten in silence.30

Leisure time followed, however, the inmates were monitored. Playing cards and games of chance were not allowed, nor was smoking or drinking alcohol, and the inmates were not allowed to go to the sleeping quarters until bedtime. Nonetheless, the break from toil and the opportunity to socialize must have been welcomed.

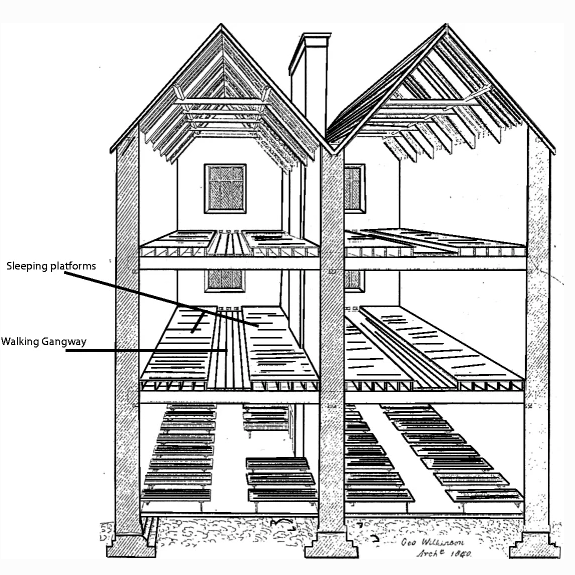

Paupers were required to be in bed with lights out by 9 p.m. The bell would ring again, prayers were given, regulations read, fires drawn, and the paupers were sent to the sleeping quarters. The inmates slept two to a straw mattress that were set upon a platform. The platforms lined the sides of the rooms at a height of eight inches from the ground. A walkway stretched between the two rows for access, and two large urine tubs were provided in each ward—which frequently overflowed. At lights out, the door to the sleeping room was locked and the key given to the master. 31

On Sundays, Good Friday, and Christmas day, the workhouse inmates didn’t have to work, and they were given meat for dinner on Christmas day. At Christmas time, the better angels of the community came out, and great efforts were made to ease the lot of the workhouse patrons. Gifts of bread and fruit, toys for the children, Christmas trees, candy and other treats were often provided by people in the community. If only for a day, at least the paupers would know comfort and joy.

RELATED CONTENT—CHRISTMAS IN THE WORKHOUSE

Regulations at the workhouse were strict and enforced by threat of withholding food, ejection, or prison. Reportedly, “[a]nyone who refused to work went without their next meal. Refuse twice, and you were punished at the discretion of the overseer.” 32

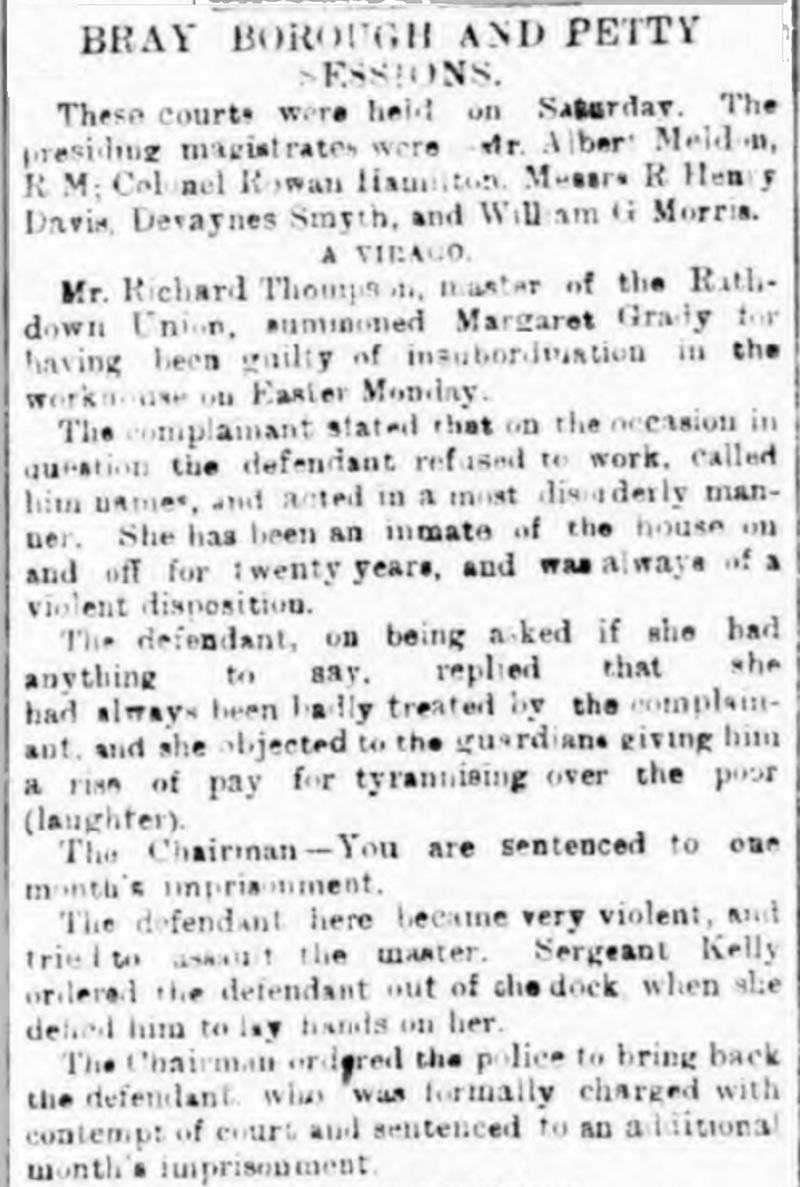

From newspaper accounts, we know that Margaret didn’t always submit gracefully to the taskmasters, and in time she developed a reputation for being difficult. One day Margaret refused to do the work. When the overseer called her on it she attacked him and was brought before the magistrate. There is no way to know whether Margaret’s refusal was justifiable or malicious. Was she sick? Was the master making an unreasonable request? Or was Margaret just fed up with the depravation and authoritarian taskmaster? When asked by the court to tell her side of the story, Margaret said “she had always been badly treated by the complainant [the master] and objected to the Guardians giving him a rise in pay for tyrannizing over the poor.”33 The newspaper reported there was laughter in the courtroom after this exchange.

Master Richard Thomson countered by saying, “She has been an inmate of the house on and off for 20 years and was always of a violent disposition.” Not surprisingly, the magistrate sided with the master and sentenced Margaret to a month in prison for refusing to work. When her sentence was read, she again attacked the Master Thomson and defied the bailiff who ordered her out of the docket. Margaret was given another month in prison for contempt of court.34

It is possible that Margaret’s misbehavior was calculated—living conditions at the workhouse were worse than those at the prison, so inmates might on occasion act out so they would be sent to where accommodations and food were better. On at least three other occasions, Margaret was reprimanded and even imprisoned for her behavior in the workhouse.

Margaret Martin turned 21 years old in 1866. Her childhood had taken many turns—orphaned at nine or ten years old, then sent to a strange, far-off land to live with family who were strangers. She spent many of her teenage days in a workhouse subjected to Spartan living arrangements and authoritarian masters. Although others of her siblings had, Margaret learned neither how to read nor write.

But despite all that was lacking in her young life, Margaret did not succumb to many of the destructive behaviors that were common in her world. It has been instructive in researching Margaret’s life to come across other women named “Margaret Martin” in Ireland, to see what happened to them. There were women named Margaret Martin who were thieves—they stole clothing, snuff, a metal sauce pan, a kettle and a Bible, six chairs, “purse and money,” and turnips, which is larceny and a felony if you steal enough of them. Another Margaret Martin was accused of prostitution and annoying passengers. She was tried the same day and sentenced to serve a week or pay 2£. She did the time.35

Assault, forgery of postal orders, using profane language, and blocking the road—these were all crimes that other Margaret Martins committed, but ours never did (or at least she didn’t get caught doing them!). Margaret was never charged with being drunk and disorderly, for which her husband, Daniel Grady was jailed several times. In what was a dreary, meager existence, Margaret did not sink so low.

In Ulysses, James Joyce mentions the Rathdown Union Workhouse as one of the memorable places in Ireland, adding this melancholy thought: “All these moving scenes are still there for us today rendered more beautiful still by the waters of sorrow which have passed over them and the rich incrustations of time.”36 Certainly the “waters of sorrow” passed over Margaret in her days at the Rathdown Union Workhouse in Loughlinstown, and many scenes of her life were poignant, moving, and beautiful.

Margaret’s Seven Years Away

Book 13 of the Rathdown Workhouse Admissions and Discharge Records, which covers admissions from March 1867 through September 29, 1870, is missing so there is no way to know how often or long Margaret’s stays at the workhouse continued between 1867 to 1870. However, judging by the diminishing frequency of Margaret’s visits leading up to the period of missing records, we can extrapolate that Margaret made her way outside of the workhouse more often than not going forward. The existing books of workhouse admissions bears out that fact—from October 1870 through February 1878, Margaret is completely absent in the workhouse records. Where was she and what was she doing for these seven plus years?

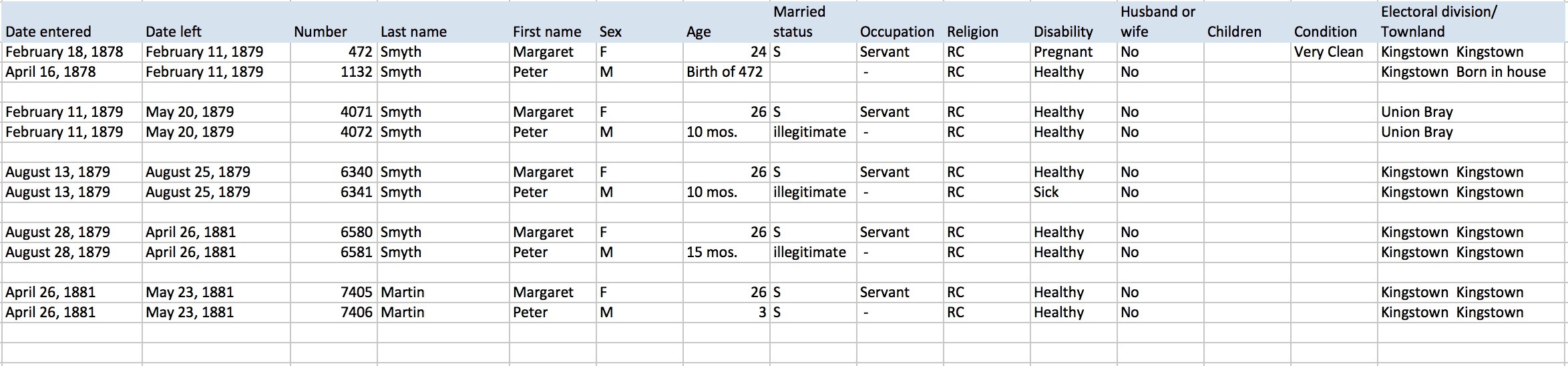

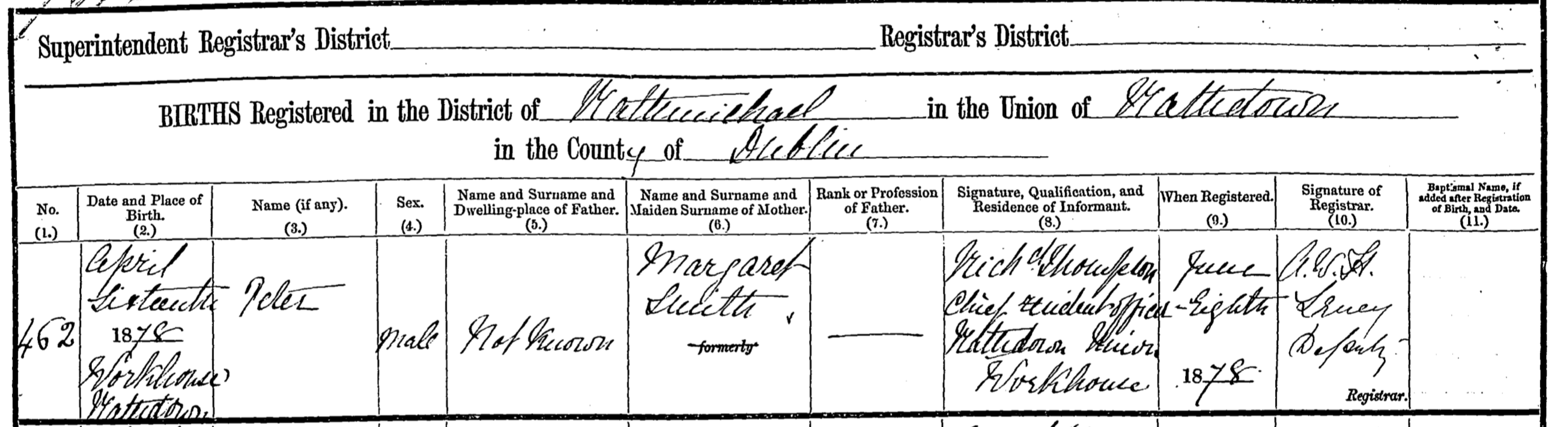

We have at least a partial answer. When Margaret returned to the workhouse on February 18, 1878, she did so under a different name—Margaret Smyth. She was also seven months pregnant. Margaret gave her residence as “Kingstown,” and her condition was noted, unusually, as “very clean.” She had obviously came from a place where she could take care of her needs. Margaret gave birth to a son, Peter Smyth, on April 16, 1878. Margaret and Peter continued their stay at the workhouse until February 11, 1879.38

Why did Margaret enter under a different name? Where had she been for the previous seven years? Who was the father of her child? Through a combination of DNA testing and record analysis, we are beginning to find answers that make sense of Margaret’s odd behavior.

The John Smyth Family

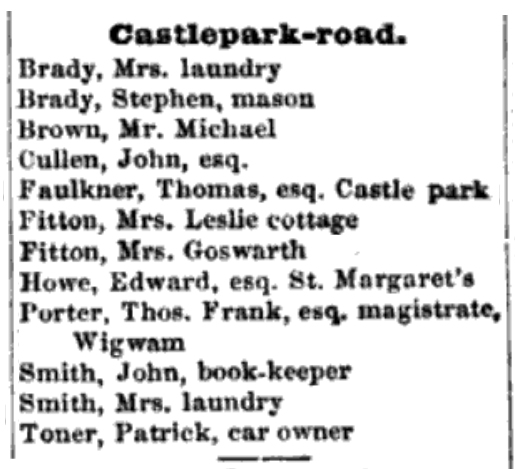

John Smyth was reportedly born in about 1815 in Tinahely, County Wicklow.40 He married Mary Smith in Kingstown Parish on April 2, 1833. John and Mary both listed their residences as “Glassdoole” [Glasthule].41 John was a bookkeeper according to both his son Daniel’s 1872 wedding document and the 1859 Thom’s Almanac and Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.42 John and Mary lived on Castlepark Road in Dalkey, and they eventually had nine children—seven boys in a row followed by two girls. It’s not clear exactly what happened to all of John and Mary’s offspring, however, we do know that three of the boys stayed in Dublin and had children of their own.

Daniel, the sixth son, was born in 1844. He became a shoemaker, and he and his wife, Ellen Magee, had 13 children. They lived on Sandycove Road in Glasthule (which was sometimes designated as part of Kingstown).43

The seventh son, Valentine Smyth, was born in 1847, and he became a master carpenter—by the 1901 Census, he was a foreman, and by 1911 he was the Clerk of Building Works.44 Valentine and his wife, Ellen Hinch, had 12 children, including seven sons and five daughters. Additionally he opened his home to some of his other siblings—Ann Smyth lived with him on both the 1901 and 1911 Censuses, as did his older brother Peter, also a carpenter and born in 1842.

DNA Speaks

Three strong indicators point to whom the father of Peter might be.

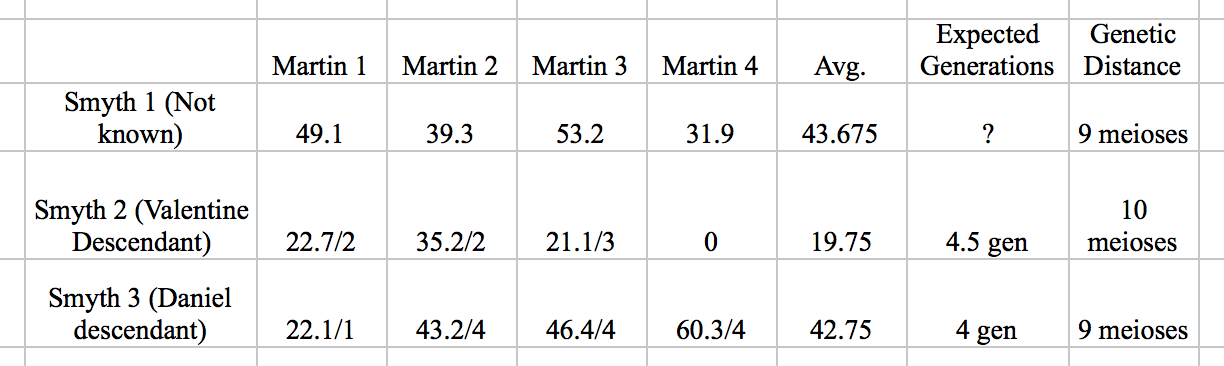

1.) Autosomal DNA testing of Peter Martin’s grandchildren has shown strong DNA matches between them and the descendants of both Valentine and Daniel Smyth in comparable degrees of genetic distance. Children inherit one-half of their DNA from each parent, and then in turn pass their parent’s DNA on to their children. Two people who are descended from the same man and/or woman will have identical snippets of DNA passed on from that common ancestor. By measuring how much identical DNA the two people share, you can identify within a statistical range how many generations back they shared a common ancestor—the more identical DNA, the fewer generations to the common ancestor. In other words, DNA testing shows that Peter’s father has an 85% chance of being one of John’s sons, although probably not Valentine or Daniel. (If Valentine were Peter’s father, Peter’s descendants would manifest higher amounts of matching DNA indicating a shorter genetic distance to the descendants of Valentine than to Daniel’s descendants—and vice versa. Such is not the case.) There is a 15% chance that Peter’s father was John’s nephew.

2.) Additionally, 37-marker Y chromosome testing was done with a male-line descendant of Peter Martin and with one of John Smyth’s male-line descendants. Unlike Autosomal DNA testing (which measures matching genetic material in X chromosomes), the Y-DNA genetic material (the Y chromosome) is passed on from father to son without dilution or changes apart from naturally occurring mutations. The test results from these two men make for strong evidence—there was a one-step genetic distance between the two, giving a 83.4% chance that they shared an ancestor within four generations. (Each of the men are four generations down from John Smyth.)45

3.) The two methods of DNA testing give strong evidence that Peter’s father was one of the sons of John Smyth. But which one? To answer this question, we turn to written records. When Peter Martin returned from serving in the military in the Boer War, he got a job working for Guinness Brewery in August of 1902. To fulfill the employment requirements, Peter needed a copy of his birth certificate—which unfortunately gave his name as Peter Smyth instead of Peter Martin. Peter had to obtain a letter from Margaret to explain the discrepancy. This task may have spawned new discussions leading to new information for when Peter subsequently married Catherine O’Toole in 1903, he listed his father’s name as “Peter Martin,” with an occupation of “carpenter.” (See Fig. 26.)46 Peter Smyth was indeed a carpenter—he was also the right age (three years older than Margaret) and unmarried. All things considered, Peter seems the one most likely to have fathered a child with Margaret.

Piecing together the evidence from Autosomal and Y-DNA testing, Peter’s marriage record, and John Smyth’s family records, we have concluded that Peter Smyth, born 1842, fifth son of John Smyth, is probably the father of Peter Martin.

Unlike Daniel who married in 1872, and Valentine who married in 1877, Peter did not marry. The 1871 Census shows him living in Cheetam, Lancashire, England, working as a joiner.47 At some point Peter returned to Ireland, although we don’t know specifically when. Peter does not appear in many records, but in the 1901 and 1911 Censuses, we find him living in his brother Valentine’s home.48

The Smyth family home appears to have been on Castlepark Road in Dalkey (although also occasionally placed as part of Kingstown or Sandyford). John Smyth is shown living on Castlepark Road as early as 185950 and until his reported (but unverified) death in 1879. Valentine Smyth lived on Castlepark Road in records from 1877, 1883, and 1901, probably in the same house his father did.51 Castlepark Road was sparsely developed at that time (See Fig. 27.) and contained several large estates (such as St. Margaret’s and Goswold), a group of eight terraced two-story homes, and a few small lodges and cottages (such as the Lilac Cottage).52 Judging by information given in directories, the larger estates were often unoccupied. At times the Smyths were listed in these directories along with merchants, lawyers, and various men deemed “esquire.” But just as often the Smyths were left out, likely not meeting the social criteria to merit a listing.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly which of the Castlepark Road houses was home to the Smyth family—neither the directories the Smyths appear in nor the 1901 Census contain actual street addresses. However, I would guess they lived in one of the terraced homes nearby or even adjacent to the Park Lodge.

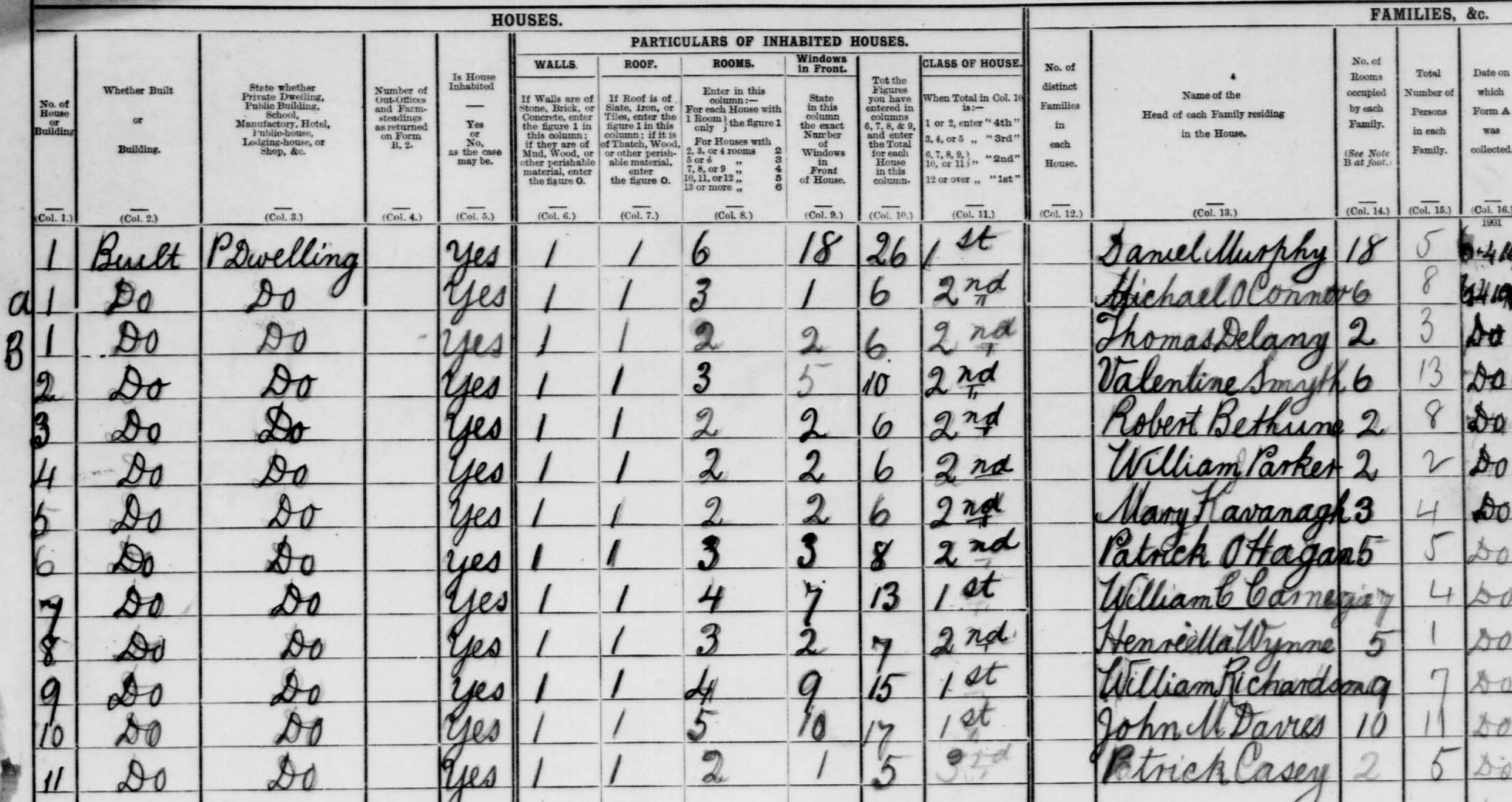

Whichever building it was, Peter Smyth grew up in the house on Castlepark Road, and he probably lived there much of the time as an adult also. The 1901 Census shows there are 11 domiciles on Castlepark Road, and the Valentine Smyth family occupied the third on the list, including Peter Smyth. (See Fig. 28.) Their home had six rooms with five windows that faced the front of the house, and was valued at 2 pounds. The first house listed on the street had 18 rooms and 18 windows that faced the front. Mr. Daniel Murphy, a merchant, and his wife Catherine, a lady, lived there with their three servants.53

It’s possible Margaret was working as a servant in the Smyth household some time between 1870 and 1878, or even at the larger house just two doors down. Either home would have felt luxurious to the girl who had only known two-room, two-window stone cottages. Remember that when Margaret returned to the workhouse, her status was “very clean,” and she claimed “Kingstown” as her place of residence, which could certainly apply to Castlepark Road.

Wherever Margaret was working in Kingstown, it’s apparent that she met and conceived a child with Peter Smyth. But their encounter was more than just a casual one. When Margaret took the surname Smyth upon entering the workhouse, it seems most plausible that she did so to pressure the baby’s father into marrying her and legitimizing his son. That she would hold out for three years with the assumed name shows Margaret’s usual stubborn flair. Indeed this theory is strengthened by the fact that Margaret only changed her name back to Martin when a new romantic interest entered the scene. On April 26, 1881—the same day Margaret reregistered using the Martin surname—her future husband, Daniel Grady, also checked into the Rathdown Workhouse. His workhouse number was 7420, only a few digits higher than Margaret and Peter’s at 7405 and 7406.54

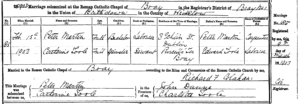

Four weeks later, on May 23, Margaret, Peter, and Daniel checked out of the workhouse and traveled to Little Bray. Margaret and Daniel were married at the Catholic Church in Little Bray by Father Joseph Burke. Come July they all returned to the Rathdown Workhouse.

TO BE CONTINUED

NOTES

1. This information is taken from an 1885 prison register on one of the occasions when Margaret was jailed for defying the workhouse authorities. The entry gives this information: Margaret Grady, 36 years old, 5’3”, Brown hair, sallow complexion, 148 pounds, born in Glasgow, entered August 13, 1885, sentenced to 14 days for insubordination in workhouse, and another month for same at Bray on August 8, 1885. Released 26 September 1885. See “Margaret Grady” Prisoner 3458 in DublinN-Grangegorman Female Prison General Register, 1885-1886, Book no 1/9/30, Item 1. Record sourced from findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com).

2.That may evidence the fact that the family were not regular church attenders, or it may be that Rosanna and William took the extra trouble to have Peter and William christened in Ireland or elsewhere and the records have been lost. See “Scotland Roman Catholic Parish Baptisms,” The Scottish Catholic Archives, Airdrie, St Margaret. Accessed through findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com).

3. These details were derived from measurements of maps and later Census surveys (after 1851) that included information about domiciles. Maps courtesy of the National Library of Scotland, Ordnance Survey, 25 inch to the mile. Surveyed in 1858 and published in 1860. Maps used include Lanarkshire, III.14 (New Monkland) and Lanarkshire, VIII.2 (New Monkland). See https://maps.nls.uk/geo/find/#zoom=17&lat=55.89833&lon=-3.97781&layers=101&b=1&z=0&point=55.89590,-3.97412.

4.“The Housing Condition of Miners Report” by the Medical Officer of Health, Dr John T Wilson, 1910, sourced

from http://www.scottishmining.co.uk.

5. “Scotland Census, 1851,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-X9TW-2P?cc=2028673 : 21 May 2014), > image 1 of 1; from “1851 England, Scotland & Wales census,” database and images, findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com : 2012.); citing PRO HO 107, The National Archives UK, Kew, Surrey.

6. See “Trial papers relating to Robert Rouatt for the crime of culpable homicide, or culpable neglect of duty at No 4 Rochsoles Pit, Drumshangie.” Tried at High Court, Glasgow, 30 Sep 1852, Reference: JC26/1852/278, National Records of Scotland.

7. See “Rochsoles—Extract from 1871 Truck Report,” Scottish Mining Website, http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/150.html. Visited February 8, 2022.

8. See Medical Report from “Trial papers relating to Robert Rouatt for the crime of culpable homicide, or culpable neglect of duty at No 4 Rochsoles Pit, Drumshangie.” Tried at High Court, Glasgow, 30 Sep 1852, Reference: JC26/1852/278, National Records of Scotland.

9. “Edward Martin,” Birth:2 Jan 1853, Baptism date: 9 Jan 1853, St. Margaret, Airdrie, Scotland Roman Catholic Parish Baptisms, 1842-1977, Vol. 1.

10. Commissioners for Inquiring into the Employment Condition of Children in Mines Manufactories, and W. C. The Condition and Treatment of the Children Employed in the Mines and Colliers of the United Kingdom. Carefully Compiled from the Appendix to the First Report of the Commissioners With Copious Extracts from the Evidence, and Illustrative Engravings. 1842.

11. Edward’s christening record lists his mother as “Jane Martin” and his father as “William Martin.” We believe Rosanna and Jane are the same person. Just a few months before Edward’s birth, Rosanna had given testimony for the Rowatt trial as “Jane Bracken or Martin.”

12. “Scotland Census, 1861,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9398-Z29N-4D?cc=2028677 : 21 May 2014), > image 1 of 1; from “1861 England, Scotland & Wales census,” database, findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com : 2012); citing PRO RG 9, The National Archives UK, Kew, Surrey.

13. “Scotland Census, 1861,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9398-Z2DV-3?cc=2028677 : 21 May 2014), > image 1 of 1; from “1861 England, Scotland & Wales census,” database, findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com : 2012); citing PRO RG 9, The National Archives UK, Kew, Surrey.

14. “Scotland Census, 1861,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9398-DT79-9?cc=2028677 : 21 May 2014), > image 1 of 1; from “1861 England, Scotland & Wales census,” database, findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com : 2012); citing PRO RG 9, The National Archives UK, Kew, Surrey.

15. On June 25, 1860 we find the first record for Margaret Martin as she enters the Rathdown Workhouse at Loughlinstown. Her record reads “Margaret Martin, 16, Single, Servant, Healthy, RC [Roman Catholic], Dirty [her condition], Union [Parish she was from] Ballycorus [her home].” Unfortunately any records of possible stays before 11 October 1858 are lost—Record books 7 and 8 are not available.

16. “An Irishman’s Diary,” The Irish Times, Monday, August 22, 2005. <https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-1.483057>. Visited February 12, 2022.

17. The only records we have to track the where the Brack siblings lived at this time are the birth and christening records of their children. Patrick Brack and Ann Mason had a daughter Catherine Brack who was born in November 1864. Their residence on the birth document is given as Loughlinstown. (See “Ireland Births and Baptisms, 1620-1881”, database, FamilySearch [https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F5L5-J2R : 15 February 2020], Catherine Brack, 1864). Likewise Anthony Brack and Margaret Lacey had a son, John, born in 1855 in Sandyford, and Edward and Mary Ann MacEneny Brack’s children were born in Ballycorus.

18. See Rob Goodbody, Sir Charles Domvile and His Shankill Estate, County Dublin, 1857-1871,

(Dublin: Four Courts, 2003) to read more about this fascinating house and the legal battles the Brack family undertook to stay there.

19. Rob Goodbody states “It was common practice to put a corrugated iron roof over the top of the thatch. That meant that the house could remain occupied during the works, as the roof was not removed. The thatch also helped insulation.” (“Re: Ballycorus Lead Mines walk” Message to Toni Thomas. 4 August 2019. Email.) Mr. Goodbody’s knowledge has been invaluable in compiling this information.

20. Source of Photos: Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council Planning Application, submitted by Peter Brack, 4 February 2004.

21. This information comes from this information comes from the Rathdown Poor Law Union Admission+Discharge BG 137/G 10, Workhouse admission and discharge records, Books 38-40, August 1862 to September 1863; Book 42-45, March 1864 to March 1866 (Book 41 is missing). Records sourced from findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com).

22. Union Rathdown, Dublin Poor Law Unions Board Of Guardians Minute Books, Poor law records of Rathdown Poor Law Union, 1841-1921, Minute Book A 58 MAR 1862 TO SEP 1862, Meeting date 13 Aug 1862, Page 179. Record sourced from findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com).

23. Powell, Malachy. “The Workhouses of Ireland.” University Review 3, no. 7 (1965): p. 4, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25504718.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid., p. 7.

26. Ibid., p. 10.

27. Ibid., p. 12.

28. Ibid. See also “The History of Irish Workhouses,” <https://www.findmypast.com/articles/world-records/full-list-of-the-irish-family-history-records/institutions-and-organisations/dublin-workhouses-admission-and-discharge-registers-1840–1919>, visited February 11, 2022.

29. Powell, p. 12 and Holly Thomas, “A day in the life of a Dublin workhouse,” Irish Central, September 4, 2020. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-dublin-workhouse. Visited February 12, 2022.

30. Powell, p. 12.

31. Ibid., pp. 12–13.

32. See Holly Thomas, “A day in the life of a Dublin workhouse,” Irish Central, September 4, 2020. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-dublin-workhouse. Visited February 12, 2022.

33. “Bray Borough and Petty Sessions,” Freeman’s Journal, 18 April 1898, p. 3.

34. Ibid.

35. These women named Margaret Martin were found in the Irish Prison Registers (1790-1924), including Grangegorman and Mountjoy prisons in Dublin. Sourced from findmypast (http://www.findmypast.com).

36. James Joyce, Ulysses. London: Bodley Head, 1955, p. 316.

37. Margaret Smyth at Rathdown Poor Law Union Admission+Discharge BG 137/G 17, Workhouse admission and discharge records, Book 15 (30 September 1870) – Book 17 (9 April 1878, no. 1040).

38. Ibid.

39. Peter’s birth certificate citation.

40. Ancestry user “blsmith” asserts John Smyth was born ca. 1815 in Tinahely. There is no documentary support for this at present.

41. Marriage of John Smith and Mary Smith, December 2, 1833, Kingstown; County of Dublin; Archdiocese of Dublin. Marriages, Nov. 1833 to Feb. 1834, p.4388.

42. “Ireland Civil Registration Indexes, 1845-1958,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FY91-MMW : 10 March 2018), MARRIAGES entry for Daniel Smyth; citing Dublin South, 1872, vol. 2, p. 761, General Registry, Custom House, Dublin; FHL microfilm 101,251, and Thom’s shows John Smyth, bookkeeper, Thom’s Almanac and Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 26, Dublin: ALEX THOM and SONS, 1859, pp. 1188–89.

43. See “Daniel Smyth” in Census of Ireland 1901/1911. The National Archives of Ireland. http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai003746955/: accessed 16 February 2022.

44. See “Valentine Smyth” in “Ireland Census, 1901,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QPB2-F2QL : 3 November 2021), Valentine Smyth, Dalkey, County Dublin, Ireland; citing Census, Dalkey, County Dublin, Ireland, 0000099489, Public Record Office of Ireland, Belfast, and “Ireland Census, 1911,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QY8D-VMMM : 26 December 2018), Valentine Smyth, 1911; citing Dalkey, County Dublin, Ireland, Census, National Archives of Ireland, Dublin.

45. Autosomal DNA testing was done through Ancestry, while Y-DNA testing was done with FamilyTreeDNA. Some comparisons were also done on Gedmatch. The methodology consisted of creating a pool of matches shared by all or most of the Martin cousins. Matches that were also shared with O’Toole or Martin cousins were removed from that pool, leaving only matches with people descended from Peter’s father. Ancestral trees were examined to find a common ancestor among those remaining in the pool. That common ancestor proved to be John Smyth with 85% certainty. Genetic distance and relationship percentages were determined using an average of the amount of centiMorgans shared by the Martin cousins with Smyth 2 and 3, as the pedigree for Smyth 1 was not known.

46. “Ireland Civil Registration Indexes, 1845-1958,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FY88-7MV : 10 March 2018), MARRIAGES entry for Peter Martin; citing Rathdown, Jan – Mar 1903, vol. 2, p. 804, General Registry, Custom House, Dublin; FHL microfilm 101,260.

47. “England and Wales Census, 1871”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KZPQ-2VB : 15 July 2021), Peter Smyth in entry for Ellen Jane Marsh, 1871.

48. See “Ireland Census, 1901,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QPB2-F2QL : 3 November 2021), Valentine Smyth, Dalkey, County Dublin, Ireland; citing Census, Dalkey, County Dublin, Ireland, 0000099489, Public Record Office of Ireland, Belfast.

49. 1901 Census House and Building Form (B1) for Castlepark Road, Census of Ireland 1901/1911. The National Archives of Ireland. http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai003740892/: accessed 17 February 2022.

50. Thom’s shows John Smyth, bookkeeper, Thom’s Almanac and Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for the Year, Volume 26, Dublin: ALEX THOM and SONS, 1859, pp. 1188–89.

51. See “Valentine Smith” in Marriages, June 11, 1877, at Ballybrack, National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 09211 / 02; “Valentine Smith” in Thom’s Directory of Ireland, Alexander Thom, Dublin, 1883, p.1532; and “Valentine Smyth” in “Ireland Census, 1901,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QPB2-F2QL : 3 November 2021).

52. “Ordnance Survey Ireland (OSi) 19th Century Historical Maps,” held by Ordnance Survey Ireland. © Public domain. Digital content: © Ordnance Survey Ireland, published by UCD Library, University College, Dublin. <http://digital.ucd.ie/view/ucdlib:40377>

53. 1901 Census House and Building Form (B1) for Castlepark Road, Census of Ireland 1901/1911. The National Archives of Ireland. http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai003740892/: accessed 17 February 2022.

54. See “Peter Martin” Workhouse number 7406, Rathdown Poor Law Union Admission+Discharge BG 137/G 18, Workhouse admission and discharge records, Book 19 (7 December 1881, no. 9040), Item 2.