Ah, the joy of a newborn baby!

Such tragedy, the death of a child!

Sometimes fate only gives us a scrawled record to represent great moments in our family history. Birth, marriage, death—sometimes we have only imagination to fill in the human details. Family members couldn’t or just didn’t take a photograph or record the experience in writing.

(That will change once I’ve finished my Time Machine! I’m going back with a camera!)

BUT, sometimes we get lucky! SOMETIMES if we are wily and persistent we can read between the lines and feel the anguish, feel the joy, sense the person in the record.

This is why I LOVE to collect SIGNATURES!

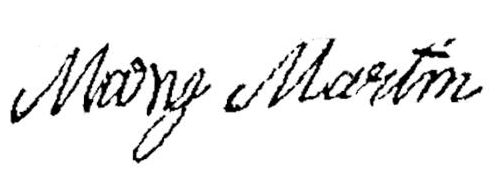

Let’s talk about Mary Martin; Mary’s signatures definitely tell a story. The first I offer is from when she was 18 years old. The girlish scrawl has pretty loops and shows an immature hand. I think I would have liked this girl who wrote so carefully and prettily.

The second signature shows Mary at 38 in 1888. Her hand is more mature, less careful. A busy, working, single mother, she didn’t have time to be too particular, but still favored the fancy curls. I’ve been there, haven’t you?

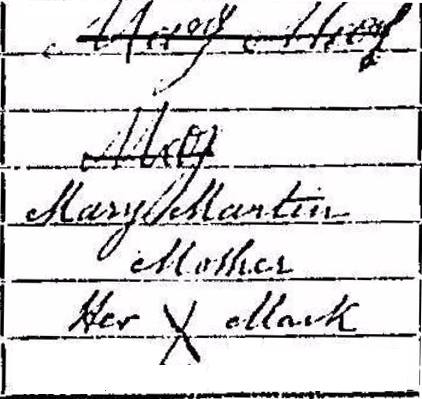

Finally, the third Mary set tells a tender and painful story. Mary Martin gave birth to her third child, a boy, on January 27, 1878, in Portobello, Scotland. Her first child she had named Thomas, after the uncle who raised her. The second she gave her own name, Mary. This one Mother Mary lent her father’s name, William Martin, who died when she was only a year old.

Sadly, when little William was only two years old, he became very ill. For a month he suffered with bronchial pneumonia and diarrhea; for a month Mary would have had to nurse him, day and night, watching him suffer and waste away. For a month she would watch helplessly, sending fervent prayers to heaven, hoping against hope, dreading the increasingly inevitable outcome.

On August 28, 1880, little William Martin died, in the same house he was born in, #10 Pipe Street in Portobello. He was two years, seven months, and one day old.

By then Mary must have been physically wasted, emotionally spent. She signed William’s death certificate, in full grief, the very day of his death. You can see on the document that Mary struggled to write her name, but messed it up and scratched it out. A second time she attempted the signature, and again made a mess of it and scratched it out.

I imagine at this point R. Pasley Stevenson, the recorder, stepping in with his deep, gruff brogue: “Aye, lass, let me give a hand.” He wrote her name, and she obliged with her “mark,” an X.

When I see this I weep for Mary, heartbroken, distraught, and I think I comprehend just a bit of her pain. When I see this, i consider my own heartaches, and feel she would have understood. When I see this, I feel I have made a friend. And isn’t that what family history is all about?