Long ago the echo of their footfalls faded. Time continues to erode the imprint of their passage.

Perhaps they could not read nor write, and left no personal records or family Bibles. How then can we find our elusive ancestors? Sometimes we have to be creative and read between the lines. But with luck and plenty of perseverance, we can overcome the lack of records and still catch a glimpse, an outline, a subtle feature of who our ancestors were by examining the detritus of time for remnants of their passage.

Anthony Brack was a small farmer and carter in County Dublin, Ireland in the late 1700s and 1800s. Catholic and poor, he left few evidences of his life; yet, his living descendants number in the thousands, have spread throughout the world, and have made their marks in medicine, business, government, education, the arts, the military and in athletics.

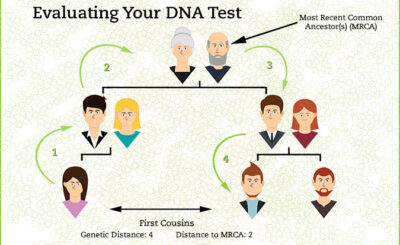

Here is his story, gleaned from birth, workhouse, land, and other public records. With a little DNA magic added to the mix.

Finding the Brack Family

Anthony Brack has mention in only a handful of documents, and even fewer by name. Still, those few documents allow us to piece together a profile of the man, hold him up against the timeline of his age, and infer somewhat of who he was and how we got here.

On 23 January 1850, Anthony Brack entered Rathdown Workhouse (See Figure 1.); his age is listed as “65” years old. His condition is given as “clean” and he is not “disabled,” but there is no reason given for his admission such as poor health. The space for married state is also left blank, so we don’t know if he was widowed by then. Anthony stayed for 12 days and checked out on 4 February 1850. It’s possible he was there for food, as this was during the famine years.

This information gives the only clue we have to Anthony Brack’s birth, which calculates to the year 1785. During the uprising of 1798, he would have been 13 years old, an age where the rebels’ cause would have held romance. The failure of the rebels, however, gave one advantage: the military roads that the British built in hopes of capturing Michel Dwyer opened up access to mining in County Wicklow. Anthony would have been 15 or 16 years old when lead was first mined at Glendalough and 21 years old when open cast mining began at Ballycorus. He may have mined at either or both places.

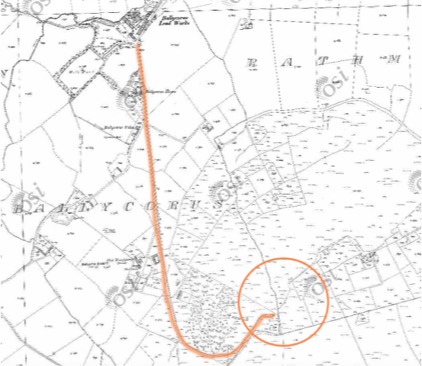

At some point in time, we presume Anthony Brack married Rose Smyth. We have no records or other indications of where (or even if) the marriage took place, however, the two began their life together about 1819, a daughter Rosanna was born about 1820. Eventually, Anthony Brack became a carter, according to the death record of his son, Thomas Brock, who died in Portobello, Scotland on 21 March 1887.1 It is likely that Anthony hauled ore in a horse-drawn cart from the mines at Glendalough to the smelter at Ballycorus.

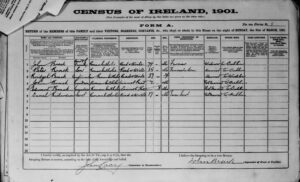

We know that two of Anthony and Rose’s sons were christened at St. Michael’s Catholic church which places the family in County Dublin in 1824 (James) and 1825 (Anthony). (See Figures 2 and 3.) The two boys’ older brother, John Brack, doesn’t have a christening record; this lack may be attributed to poverty, lack of clergy, or simply that the record did not survive. (See also discussion in footnote 8.) In any event, the 1901 Census gives John’s birth year as about 1822, and indicates he was born in County Dublin. (See Figure 4).

It appears the Brack family lived near Ballycorus at least from 1822—when the Tithe Applotment land survey records Anthony’s tenancy on the four Irish acres near Puck’s Castle. However, it is possible that Anthony may have lived at times at the Glendalough end of the mine-to-smelter relay. On 27 July 1829, Anthony and Rose christened son Edward at Glendalough, which supposes that either they were living there at that time or had family members who did.2

Mining began at Ballycorus about 1806. Mining activity fluctuates by nature; the variable prices of lead and the tendency for veins of ore to peter out meant that one day the works could be going full steam and the next everything could be shut down. When prices rose again, new shafts would be sunk to find new pockets of ore, and business would resume.

In 1825 the Mining Company of Ireland purchased the operations at Ballycorus with two dozen other mining operations around Ireland, including Glendalough. The company invested heavily in the mines but even more so in the smelter and other processing works. Soon two furnace houses operated round the clock at Ballycorus, with a shot tower (for making shotgun ammunition) and rolling mills (to make pipes and sheeting for construction), as well as 11 cottages and a school for the workers. About 130 people worked at the Ballycorus lead mine in 1859.3

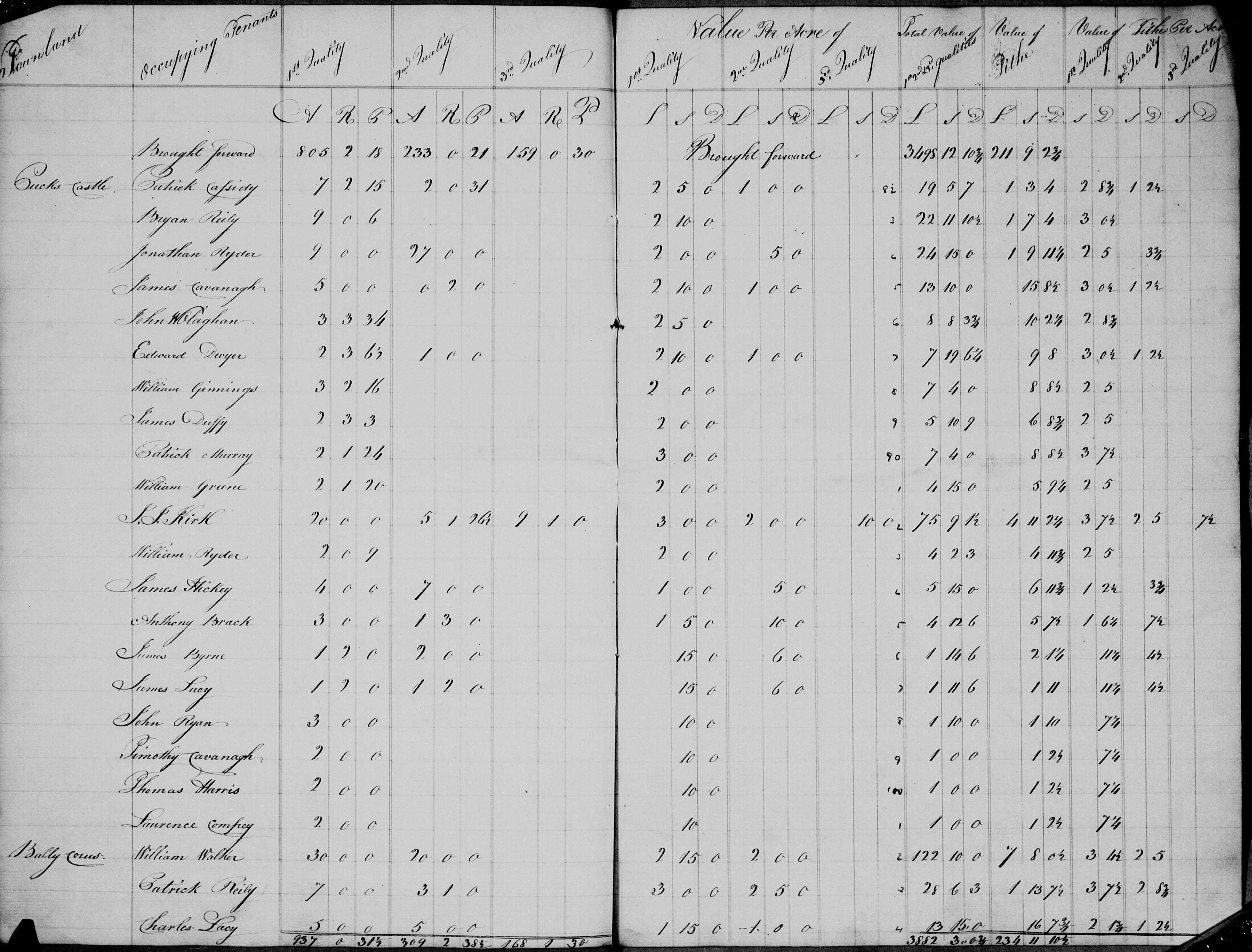

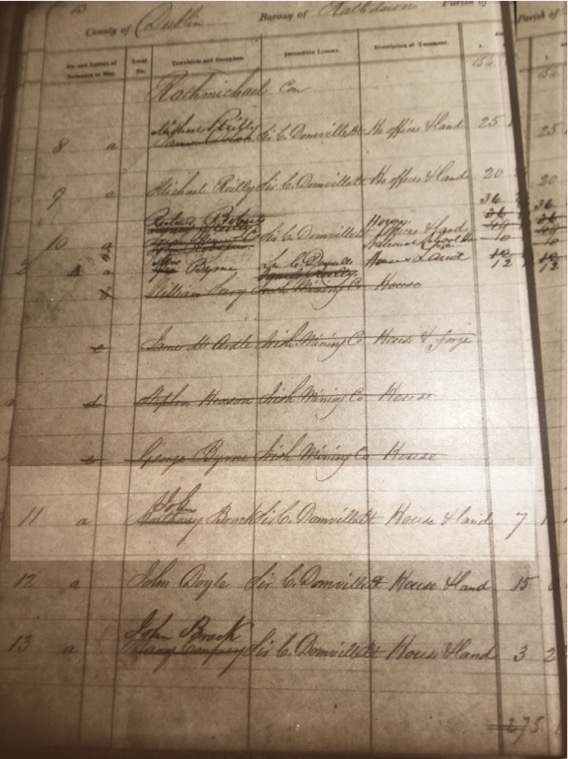

In the 1826 Tithe Applotment land survey, Anthony Brack is listed as a tenant holding 4 Irish acres 3 roods (3/4 acres) (or about seven English acres) of which 3 Irish acres were considered “first quality” (valued at 1 pound 5 shillings) and 1 3/4 Irish acres of “second quality” (valued at 10 shillings).4 The Tithe Applotment survey was conducted to assess tithes (essentially a tax) payable to the Church of Ireland to support poverty relief and other community services. (There was no support given to Catholic clergy at that time, although the majority of the population was Catholic.) Thus Anthony was required to pay some seven shillings of “tithe” in addition to the £3 15s he paid in rent to Lord Compton Domville for his rocky four-acre farm.

Unfortunately, the Tithe Applotment assessed only the production value of the land and didn’t include structures in its assessment as did the later Griffith’s Valuation. Accordingly, we don’t know what form of housing the Bracks lived in for those early years, but it probably was not the stone house we are familiar with. In 1882, John Brack testified to the Land Commission: “The land was reclaimed by his father and himself, and there are only 3 acres which can be cultivated. Before being reclaimed the land was not worth 2s 6d an acre, and some of it not worth a farthing. He built the house and would consider 6 pounds a fair rent if he could not be put out.”5

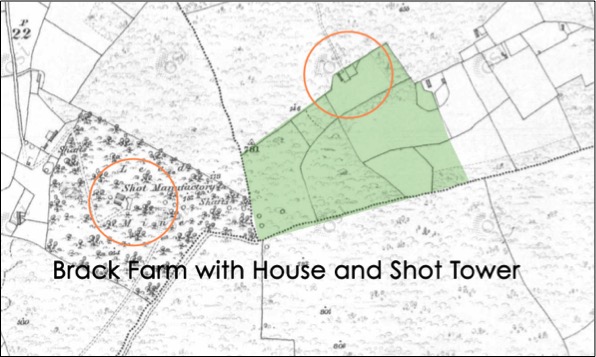

It’s not clear exactly when the stone house was built. Although they are not thoroughly executed ordnance maps, it is worth mentioning that the house does not appear in the following works: Rocque’s An actual survey of the county of Dublin (1760), John Taylor’s Environs of Dublin (1816) and William Duncan’s Map of the County Dublin (1821).6 The first appearance we see of a house is on an ordnance map published in 1843 (and later used for Griffith’s Valuation in 1848).

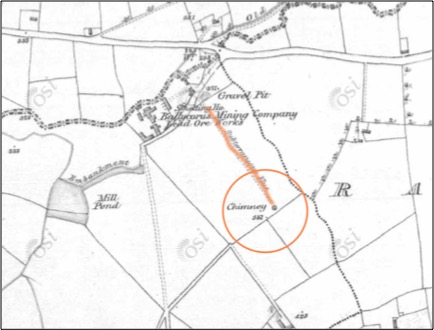

However, note that the ordnance map does not show a chimney above the Brack land, but instead the shot tower that was built in 1829. The smelter’s chimney on this map is still located a mile to the northwest.(See Figures 5 and 6.)

Originally, the Mining Company had installed an underground vent system with a chimney to handle the exhaust from the smelter. However, that flue extended only a few hundred feet away from the furnaces and pollution became a real problem for cattle and people. In 1836, the old venting system was replaced with the new chimney that stands today near the Brack house, and a new shot tower was built to the northwest of the new chimney.

The new exhaust chimney soon paid for itself. The 1.25-mile length of the arched ventilation shaft forced much of the lead to precipitate from the exhaust before it rose up through the 115-foot chimney.7 Metal doors at ¼-mile intervals allowed for removal of the lead dust which netted an additional £1,400 annually. But woe to the workers who were charged with the removal! So many health issues were traced to the lead removal that the flue tunnel became known as “Death Valley.”

Whatever housing sheltered the Bracks before the stone house, it must have been crowded. In addition to Anthony, Rosanna, and their six or seven children, a Michael and Mary Brack christened a son John in 1821 at St. Michael’s.8 They also listed their residence as “Puck’s Castle.” As there are no other Bracks listed as tenant farmers at that time, it’s quite likely they were family and lived in the Anthony Brack household.

We must also consider the possibility that Anthony’s father and perhaps, mother, also lived in the household. In 1894, John Brack testified at the Cabinteely Revision Sessions that “his father and his grandfather were in the house that he was in before him and they had votes.”9

We can’t be certain who Anthony’s father was, however the records contain two good possibilities. On 29 January 1782, a John Brack married Margaret Keogher at St Andrew’s in Dublin.10 That date fits very well with Anthony’s birth in 1785, and supports the naming patterns practiced in that place and time: Anthony Brack would be likely to name his first son John after Anthony’s father. Also, a Brack family was recorded living at Ballard, County Wicklow, in the 1766 Irish Religious Census.11 But there is not enough evidence to know for certain whether either or both documents pertain to Anthony’s father.

In any event, there may have been up to 14 people living in whatever temporary housing the Bracks used before the stone house was built.

But if living quarters were crowded, the Brack family certainly had an amazing view to comfort them. From atop Carrickgollogan, much of the neighboring towns could be seen, a view that stretched all the way to the sea.

When the Bracks built their new stone house, it was in a lower section of the farm along the property boundary line. (See Figures 9, 10, 11, 12.) The house featured two rooms, with an open fireplace in one room that exhausted through a chimney in the roof. There were apparently two windows, one per room, and the square footage of the two rooms combined measured no more than about 200 square feet. The roof was originally thatched, with corrugated iron later placed over the thatch.12

The house was very well built and remained continuously inhabited until about 2005. When the last Brack descendant tired of living without plumbing, heating, and electricity, he built a new house on additional land the Bracks had acquired through the years, on a plot that adjoined the original seven-acre farm.

Anthony Brack’s death was not recorded. Our best clue as to when he died is contained in an assessors’ House Book, one of the internal documents land assessors used when they updated the original and subsequent versions of Griffiths’ Valuation. In a House Book dated 1867, Anthony’s name is crossed out and son John’s name is written in its place. That is the only existing remnant that marks the passing of Anthony Brack.

We conclude that Anthony died no later than 1867, at about 82 years old. More than 150 years have passed since then, years that have seen his descendants multiply and scatter to every corner of the planet. His children and their children and their children’s children have taken the gift of life and genetic inheritance Anthony gave and used it to wage battle, save lives, create beauty, teach, suffer, rejoice, and speak truth.

Though all other evidences may fade, we yet remain the one sure proof that Anthony Brack lived and loved and toiled in and around the stone house at Puck’s Castle.

If you are a descendant of Anthony and Rose Brack, please note in the comments which of their children you descend through and where you were born and now live!!

NOTES

1. 1887 Brock, Thomas (Statutory Registers Deaths 684/1 31), National Records of Scotland. Thomas’s parents are named as John Brock and Jane Smith on his death record, however, we know (with 98% certainty) by DNA evidence that Thomas and sister Rosanna were the children of Anthony Brack and Rose Smyth.

2. Baptismal Record for Edward Brack, 27 July 1829, Glendalough Parish, Wicklow, Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, The National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 06474/01. Record is badly faded and difficult to read. The transcription names parents as “Thackeray Brack” and “Rose Smith,” however, the father’s name appears to be and is more likely to be Anthony.

3. See Frank McNally, Diary of an Irishman, Irish Times, 22 August 2005 www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-1.483057, visited 16 April 2019.

4. In the later Griffith’s Valuation, the same land is given as 7 acres—I believe the difference is that the Tithe Applotment used Irish acres, with Griffith’s using English acres.

5. 3 May 1882, “Land Commission at Bray,” The Daily Express, Dublin, Ireland.

6. These maps are viewable on the South Dublin Historical Mapping website, sponsored by South Dublin County Council and University College Dublin Library. They may be viewed at: http://sdublincoco.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=e0c5595b033341dea7661e248d2e9ee9//

7. The current chimney stands at 85 feet tall, however, the original tower had an additional 30 feet of brickwork rising above the stone. That portion was removed for safety reasons.

8. Baptismal Record for John Brack, 12 October 1821. Kingstown Parish, Dublin, Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, The National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 09071/02. Interestingly, there is a second baptismal record with same child, same parents, same church, same witnesses, dated November 1821. (First digit of day is illegible, but second digit is 6.) The two entries are on opposing pages of the same book. It’s possible that one christening could refer to John Brack, son of Anthony Brack and Rose Smyth, as he also was born around this time. However, it is also possible the child was christened a second time in hopes for him to recover from serious illness as was sometime the practice.

9. 11 September 1894, Irish Daily Independent, Dublin, Ireland. This statement was an attempt to claim voting rights; the latter part of his statement is false, but the first half, that his grandfather lived in the house, may very well be true.

10. The 1766 Religious Census of Ireland. The Tennison Groves Papers on microfilm LDS Family History Centre, 100173.

11. Marriage Record for Joas [John] Brack and Margta [Margaret] Keougher, 29 January 1782. St. Andrew’s Parish, Dublin, Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, The National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 09490/06.

12. Rob Goodbody states “It was common practice to put a corrugated iron roof over the top of the thatch. That meant that the house could remain occupied during the works, as the roof was not removed. The thatch also helped insulation.” (“Re: Ballycorus Lead Mines walk” Message to Toni Thomas. 4 August 2019. Email.) Mr. Goodbody’s knowledge has been invaluable in compiling this information.

13. Source of Photos: Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council Planning Application, submitted by Peter Brack, 4 February 2004.

14. From microfilm, Ireland Valuation Office Books, County Dublin, Rathdown Barony, Rathmichael Parish.