I was tasked by a friend to contribute to an art exhibit featuring women. She wanted a family heirloom to display with a short essay on the woman who owned it. I confess by time I wrote the story, it was past deadline and too long for their purposes!

(Note to self: go back and review Framing the Story. Pay particular attention to “Remember Your Audience” section.)

But I loved the assignment! I have a wall hanging crocheted by my Grandmother Weidner, and I used that for inspiration. I let my heart wander through the years as I considered what I knew, what I remembered, and what I had learned through research about Grandma Weidner.

(There were a number of Whoopie! Surprises, I’ll tell you that.)

I considered grandmother as a young girl, as a young mother, and as the seemingly ancient, chronically ill person I remembered as a child. I tried to put myself in her place, to feel her joys, her regrets, her triumphs and burdens and what peace and wisdom she may have garnered through it all.

Then I felt that I had found my Grandmother, that I could write her story.

Grandmother Elizabeth Weidner Martin Pompa was born over a hundred years ago—January 5, 1911—to Peter Weidner and Anna Auer in Cincinnati, Ohio. Elizabeth died December 13, 1980, while I was home from college on winter break; I had no real opportunity to know Grandma Pompa as an adult, but as a child, going to Grandma’s house was magic.

Her house in rural Norco, California, shared an acre-plus lot with another house. Between the two houses lie wonderland: a geodesic-domed, walk-in aviary housing exotic, colorful birds; a corral with several horses, a palomino and an appaloosa; and everywhere wandering Bantam chickens. Grandpa Pompa always seemed to be watching bull fights on their tiny black and white television set with rabbit-ear antenna. Grandma always seemed to be cooking: tamales and menudo from Grandpa’s Mexican heritage, and stuffed cabbage from her own German/Hungarian roots. She loved crafts; she loved to play Scrabble and Yahtzee at the linoleum kitchen table. It was a settled, predictable paradise for the child that was I.

Years later when I delved into family history, I discovered how unsettled Elizabeth’s life had actually been. Her parents had emigrated west as flotsam of the Mormon gathering; a cousin by marriage, Johann Schweberger, had been one of the first Hungarian converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Johann founded the Royal Shoe Repairing Company in Salt Lake City in 1908, and recruited Elizabeth’s father to come west to work for him; in 1918, the family moved to operate a branch in Milford, Beaver County, Utah. Milford was a rough frontier town, even then. It had blossomed to support the boom of the nearby silver mine in Frisco, had later grown to accommodate nearby livestock ranches, and in time became a divisional station of the Utah Southern Railroad. In 1918, each of those industries still strove in the streets of the small town. Whether due to an uncertain economy or some other lack, Grandma’s family was very poor: the parents and 14 children lived in cramped quarters behind the shoe store.

There is little record of Elizabeth’s life in Milford. She married Edward Harry Martin on April 20, 1929. He was the local mechanic and drank too much. Elizabeth was barely 18; Harry was 39 years old. Elizabeth gave birth five months after their wedding to a baby girl, and my mother the next year, and another girl the year after that.

After six years and five children, Elizabeth left Harry and married Melquiades Pompa, a Mexican national who worked for the railroad in Milford. His work took them back and forth to California, at which times she would leave her children with their father or Melquiades’ sister. Eventually, custody of Elizabeth’s children was taken from her and given to Harry, as a court judgment deemed she had abandoned them.

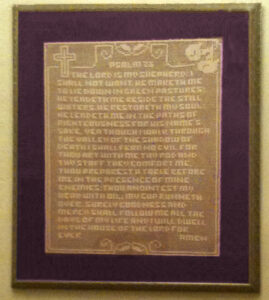

When I knew my grandmother, the passions or demons that had driven her choices had abated. I knew that she cheated at Yahtzee; I knew that my mother struggled with feelings of abandonment. But when my mother passed on to me some of my grandmother’s treasures, I was delighted to find this lovely wall hanging. I believe the work says as much or more about her as what I have gleaned from dates and details I have researched.

This piece of lace obviously represents hours of meticulous work: the carefully ordered grid; stitches counted to make solid pieces and open squares; the sum of which constitute a psalm, perhaps a prayer. “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul … Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever” (Psalm 23).

My grandmother cannot tell me where she came from, the milieu she did not choose, a nexus that colored her choices and thrust her through much chaos and pain. She came into a world that offered few options and little opportunity. But given a chance to choose, Grandmother chose this: a tribute to order, to faith, to godliness. Her work, whispering from the dust, gives me a glimpse into her heart; it forms a bridge from she who inhabited wonderland that I knew as a child, to the woman who knew heartbreak as I do and passed on to me much of who I am. For this, I thank you, Grandmother.