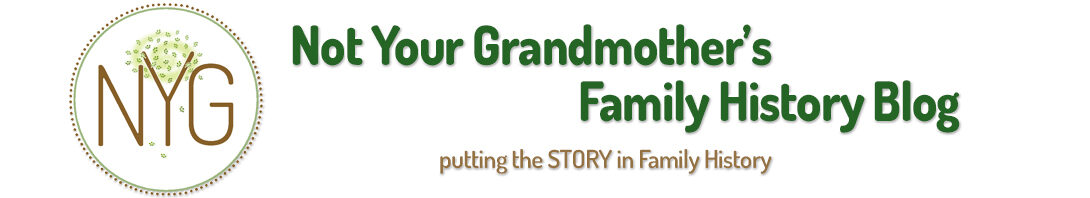

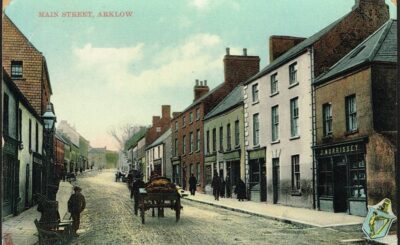

Photo above is Market Row circa 1907, looking west on First South from Main Street in Salt Lake City. Mary’s shop was toward the end of the block. Credit: Shipler Commercial Photographers Collection, Utah State Historical Society, creator and copyright holder.

The large circle of friends and acquaintances of the late William S. Martin will no doubt agree with the following description of his character: Nature had endowed him with a magnificent physical organism and with a soul that was equally as large and generous. He was a man possessed of more than ordinary energy and force of character that enabled him after years of hard toll and many disappointments to extort from the hidden treasures of nature a fortune at a period in life when he was in the full enjoyment of magnificent health. In acquiring fortune he had wronged no one. Through his efforts ho forced nature to yield from its hidden treasures and blessed the world by what he gained in adding to its wealth…. [A]ll who knew him recognized him as being a man of sterling qualities, full of generous thoughts and impulses, always ready and willing to aid those in distress.1

WILLIAM S. MARTIN, MINER

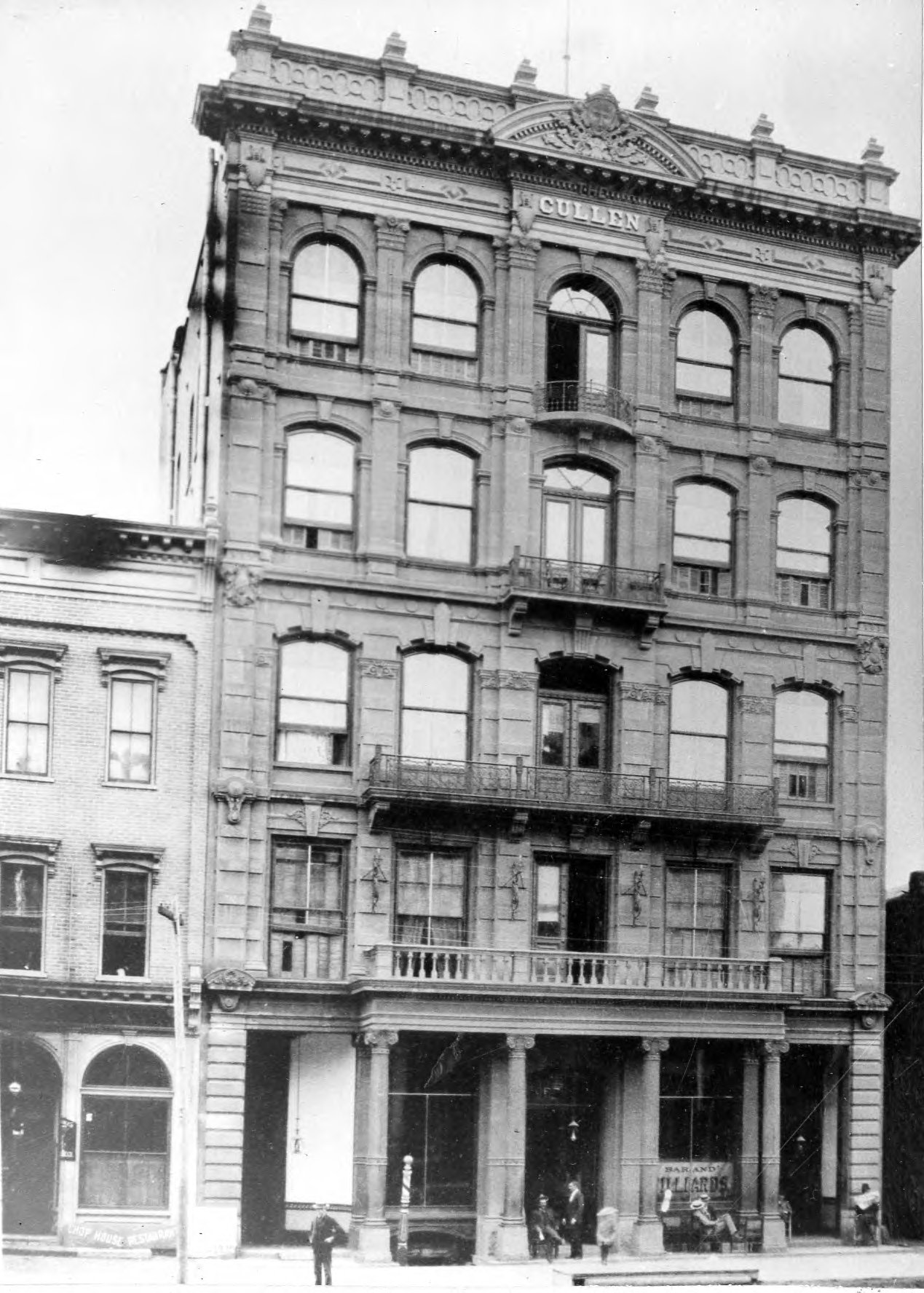

William Martin was larger than life. He was not a tall man, but he had tremendous strength and energy, qualities that stood him well in his chosen field of prospecting and mining. An 1892 newspaper account William as “a mining man of some means, and his whiskers are his pride. He is of sturdy build, and his appearance indicates his permanent address is Easy Street, Sunnyside.”2 But our story begins in the previous decade. William’s mining operations were based in Beaver County, Utah, however, business regularly brought him to Salt Lake City, where he was wont to stay at The Cullen Hotel, owned by a mining friend.

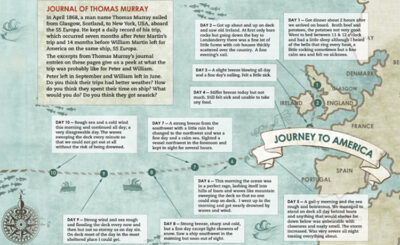

Read More about William Martin—Parallel Sourcing: Sailing to America

The Cullen boasted its status as a modern hotel on the European plan, and William claimed to have been the first guest to register when it opened.3 Its five stories rose up above the unpaved streets of Salt Lake City at 33 West Second South. A block to the north of the hotel lie Market Row on First South, a hodgepodge collection of butchers, grocers, a tea importer, and a fish market. Nestled in between the Thomas Hepworth & Sons butchers and John Murray, the barber, sat a small candy shop run by Miss Mary Lafitte. In addition to bonbons and ice cream, Mary also sold cigars—and cold, fresh buttermilk. It was this latter delicacy that appealed to William; beginning in about 1887, William would regularly stop in for buttermilk, an occasional cigar, and to flirt.

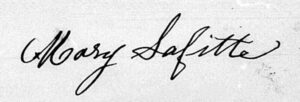

MARY LAFITTE, CONFECTIONER

Marie Lafitte—or Mary as she was known in Salt Lake City—was also larger than life. She is first seen in the 1884 Salt Lake City directory as a confectioner.4 In November 1885 she successfully applied to have the license fee waived for a peddler’s license as she was destitute.5 By 1887, however, she had purchased property in the city, eventually owning five lots by 1895.6

Mary knew how to fight for her rights—she was named in no less than seven lawsuits in a decade, both as plaintiff and defendant.7 But Mary didn’t always wait for the courts to award her what she felt was her due.

EVICTING TENANTS, LAFITTE STYLE

On October 4th of 1890, one of her tenants, Mrs. Vena Heidel, was arrears in rent, so Mary went to evict her. Mrs. Heidel took exception with a revolver in hand and ordered Mary off the property. Mary called the police and Mrs. Heidel was hauled before the magistrate, and Mrs. Heidel was released on a $1000 bond.8

Still, the tenants did not leave, so three days later, Mary again descended on the property—this time with two carpenters and a hatchet. Mary ordered the carpenters to remove the house’s doors and windows, which they did, even though Mrs. Heidel and her daughter were ill. Later when Mr. Heidel came home, he found the house freezing cold, so he went and located the windows and doors and reinstalled them. Long about dinner time, Mary returned to the Heidel residence and saw her work had been undone. Not to be foiled, she again fetched the two carpenters and once more had the doors and windows removed.9

The Salt Lake Tribune reported the encounter with glee:

Mrs. Lafitte hove in sight with all her sails set. For one moment only she gazed, and then she retired to obtain reinforcements, which she obtained in the person of the two carpenters. Then in determined accents she declared herself, said she would have these doors and windows or be-lud [blood], and again was a descent made on the Heidel household.

The latter, by the way, is no spring chicken, and when he saw the situation matters were assuming he went out and, after telling Mrs. Lafitte that he had a receipt for last month’s rent, informed her that if she didn’t get the Hades out of there he would warm her oleaginous anatomy à la a mama, a boy, and a slipper. Mrs. Lafitte wouldn’t stand any such racket, and she jumped at Heidel with her tomahawk, and would have brained him alive [like a] Sioux Injun had not the defendant, [a visiting friend named Groesdeninger], caught her mighty arm. His action maddened her, and she swore out a warrant for him [for assault].

The case was tried, Mrs. Lafitte representing the people as prosecution witness and attorney. But her eloquence availed her not, for the defendant was informed that he might go in peace. 10

WILLIAM MEETS MARY’S BUTTERMILK

Mary was no wilting spring flower, to say the least. In other newspaper accounts she is described as fair and buxom11 and—rather unkindly—fat, French, and forty.12 She was outspoken and uninhibited, but so was William. As William discovered her shop and became a regular visitor, I’m guessing he probably enjoyed the coarse and flirtatious banter they exchanged on several occasions. Although later he would claim it never took place, their exchanges seem right in character:

William: “Whose beau do you have back there?”

Mary: “I have no beau back there but I thought you was my beau. If you wish to see the beau I have back there, come on in.”

…

William: “I have come to see my lady love right from the train, with my mining clothes. I couldn’t come sooner; I bring you my picture. Can I have a kiss?”

Mary: “I don’t think we are acquainted enough.”

William: “There is no harm in a kiss. We’ve known each other a year.”

…

Mary: “I am willing to go to where your mine is.”

William; “I would not take you there for you would be lonesome. There is nothing there, not even wood. But I will sell my mine as soon as I can.”13

Mary even suggested that William claimed he was a “stud,” and they had had what William’s lawyer termed “improper relations.” That assertion William vehemently denied: “G-d forbid!”14

Mary was convinced that on October 20, 1888, William asked her to marry him when his mine was sold, and said he would take her traveling for two years and see Paris. He did indeed sell his mine in 1888, and relocated to Salt Lake City to live full time at the Cullen Hotel. Mary waited patiently with the expectation of marriage for several years, but when her repeated attempts to contact him via notes and in person were rebuffed, Mary did what Mary knew best.

In 1891 Mary filed suit against William for $25,000 in damages for breach of promise.

MARY LAFITTE V. WILLIAM S. MARTIN

William claimed he didn’t know her, he didn’t know her name, he had only bought buttermilk from her, and the only time he had gone back into her shop was on an occasion when she wanted to borrow $600. He had refused.

The newspapers had a heyday.

“Finding she could not touch her recreant lover’s heart, she resolved to touch his pocket, and promptly planted this suit in which she asks the court to place a monetary plaster over her lacerated heart.”15

“Later on, she says, he cancelled their engagement, and the castles she had been building in the air came tumbling about her ears. Having lost all claim upon his heart, Mary made a dive for his pocket, and now she claims damages, heavy damages.”16

“Mr. Martin denied all the essential points of the case and disclaimed any idea of leading the plaintiff to believe he had ever desired her as a partner of his joys and sorrows of this vale of tears. The case is what would be termed racy by the vulgar and vulgar by the refined.”17

Mary’s attorney would withdraw from the case, leaving her to present her own cause. In an attempt to salvage William’s reputation, his attorney, A. C. Ellis, managed to have William privately deposed rather than appearing in court to testify. The deposition was carried out on February 28, 1892 by Mary Lafitte. In a bizarre and colorful exchange, William repeatedly denied her assertions with “No! Never!” and “Heaven forbid!” while his attorneys repeatedly objected that the questions were irrelevant, incompetent, immaterial—and occasionally unintelligible.

Mary finally had her day in court on October 18, 1892. The court appointed Judge Cherry to assist Mary as she was representing herself, although he didn’t appear to offer much assistance aside from reading the complaint aloud, while disclaiming any knowledge of the suit. He then “occupied a seat beside her and tried to look grave.”18 William was represented this time by the Honorable H. W. Dickson (of the same firm as his precious advocate, A. C. Ellis). Mary brought forth her witnesses, but in each case their testimony was objected to and ruled “incompetent.” “Judge Zane was kept busy in calling her down and rapping for order,”19 the Salt Lake Tribune reported.

When Mary tried to question her witnesses as to her own character, that, too, was objected to.

“But your Honor,” said she, “am I not allowed to show I have a good character?”

“No,” replied the Court, “for that issue is not raised.”20

Then Mary took the stand and told her story of the faithless suitor and his broken promises.

Next William took the stand and flatly denied her claims, saying he had only seen her twice at her candy shop when purchasing buttermilk. It was a textbook case of “He said, she said.”

When both sides had rested their case, Judge Zane instructed the jury in a most unusual fashion. He told them they need not even leave the jury box, but to decide the verdict right there—which they quickly did, finding for the defendant, William S. Martin.21

The consensus in the press was well-stated by the Salt Lake Herald-Republican:

The case has been heard once before by a referee and should never have been permitted to burden the dockets of the District Court. The plaintiff conducted her own case, being unable to engage any lawyer, on such flimsy grounds was it based. The court, however, appointed Judge Cherry to assist the plaintiff on questions of law. The testimony of all of plaintiff’s witnesses was ruled out as incompetent, and then she herself took the stand. Her utter failure to make out her case, even by her own testimony, and the simple denial of Mr. Martin under oath that he had ever promised to marry the defendant, or that he had ever seen her twice, was sufficient to win him a verdict. A portion of the plaintiff’s testimony was unfit for publication and the remainder was a tissue of silly nothings, that while it created considerable amusement, had no other effect.22

Where lies the truth of the matter? It’s most likely that Mary misconstrued William’s intentions and he never intended to marry her. It’s dead certain that Mary had no idea how to go about framing or presenting her claim in a court, and it is shameful that her suit was allowed to become the subject of mockery.

Still, much of what Mary claimed went on between them probably did happen in some form. William was known to love flirting with women. Mary possessed details of William’s life that were accurate, including his birth date and place of birth, details of his mining practices, and information on the selling of his mine, the Talisman. It’s hard to believe that he only ever visited her place twice as he claimed.

The day after the trial, William went back to his mining and business and social affairs, apparently unbothered and unscathed.

Mary Lafitte also moved on—to Colorado.

Did she choose to relocate out of embarrassment or a broken heart? Or was it because the failing real estate market was devouring her investments and she needed a fresh start? In any event, Mary landed on her feet, opened another candy shop and continued her bold ways as Marie Lafitte. But that’s another story for another day.

Read Next—Mary to Marie Lafitte: The Rest of the Story!

Read Next—William Martin Goes Yukon!

NOTES

1. “Tribute to W.S. Martin,” Eli B. Kelsey, Salt Lake Tribune, February 2, 1902.

2. Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1892.

3. “Return of W. S. Martin,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 28, 1901.

4. Mary’s location is listed as 63 W. First South rather than 64 W. First South, but that is likely an error. See Utah gazetteer and directory of Logan, Ogden, Provo, and Salt Lake Cities for 1884, Salt Lake City, UT: Hearld Printing and Publishing Company, 1984.

5. Under notices of real estate transactions, “Building lot 2xl0 rods Thirteenth Ward to Mary Lafitte $550,” Salt Lake Evening Democrat, April 30, 1887, 6.

6. See “Mary Thirsts for Gore,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 6, 1895.

7. William R. George v. Mary Lafitte, (Salt Lake Tribune, July 11, 1890); People v. Groesnerriger (“The Prolonged Argument,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 11, 1890); Lafitte v. Martin (1892); C. W. Heidel v. Lafitte (“Lawyers and Litigants,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, May 4, 1892); James J. Farrell v. Lafitte, (“The Civil Jury Cases,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, September 26, 1893); Truth A Milner v. Lafitte (Salt Lake Tribune, August 16, 1896); Lafitte v. MacCord and Miller (The Salt Lake Herald, December 30, 1896);

8. See “Salt Lake Notes,” Ogden Daily Standard, October 8, 1890.

9. Salt Lake Tribune, November 11, 1890.

10. Ibid.

11. See “Lafitte v. Martin,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 28, 1892, and “Lafitte v. Martin,” Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1892.

12. “A Breach of Promise Case,” Salt Lake Herald, February 17, 1892.

13. Adapted from “Papers in Case of Mary Lafitte v. William S. Martin,” Case #9474, Third District Court, filed June 20, 1871.

14. “Lafitte vs. Martin,” Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1892.

15. “A Breach of Promise Case,” Salt Lake Herald, February 17, 1892.

16. “Lafitte vs. Martin,” Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1892.

17. “Lafitte vs. Martin,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 28, 1892.

18. “Breach of Promise Suit,” Salt Lake Tribune, October 19, 1892.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. “It Was Very Thin,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, October 19, 1892.