Ebenezer Darling was born in Thompson, Connecticut in 1818. He grew up around textile mills, began working in them as a boy, and by 1847 co-owned the Drake and Darling millworks in Holland, Massachusetts.

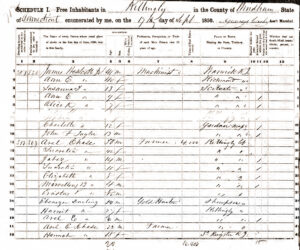

But on the 1850 U.S. Census, Ebenezer is shown back in Connecticut living with wife and son on his father-in-law’s farm. Ebenezer’s occupation is listed as “goldhunter.”

What?

I wasn’t aware there was any gold to hunt in Connecticut!

I began researching and found all manner of surprises, including a treasure of a website, The Mystic Seaport. The Mystic Seaport is the online presence for the Collections Research Center, the “leading maritime research facility” in the United States. I would love to take my grandchildren to visit the museum at the Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut. They have over two million objects, including crew lists, ship plans, art and photography, and video and audio exhibits. They also have camps, water events, and a whole lot more!

I began researching and found all manner of surprises, including a treasure of a website, The Mystic Seaport. The Mystic Seaport is the online presence for the Collections Research Center, the “leading maritime research facility” in the United States. I would love to take my grandchildren to visit the museum at the Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut. They have over two million objects, including crew lists, ship plans, art and photography, and video and audio exhibits. They also have camps, water events, and a whole lot more!

But if you can’t get to Connecticut, never fear—their online databases cover a lot of ground and are an amazing resource.

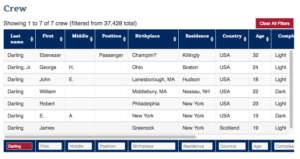

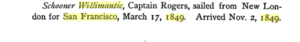

Ebenezer Darling appears in several entries in the Mystic Seaport databases. (See Fig. 2.) On March 13, 1849, Ebenezer sailed as a passenger on the inaugural voyage of the Schooner Willimantic, out of New London, Connecticut. His destination was San Francisco, California—Ebenezer was indeed a Forty-Niner, rushing to the California gold fields. Although he really wasn’t in Connecticut for the 1850 Census, it is true that he was a gold-hunter!

Before he sailed, Ebenezer obtained a Seaman’s Protection Certificate (SPC), which was a passport of sorts. The U.S. government had begun issuing SPCs to protect seagoers from impressment by the British Navy. In addition to providing protection, the Certificates helps us with a physical description of our man: Ebenezer had a fair complexion, dark hair, and was 5 foot 4 inches tall.

In my research, I found five other men from Killingly who traveled on the Willimantic with Ebenezer: Isaac Hyde, the brothers William and George Chamberlain, Smith Mitchell, and Russell B. Whitmore. These men attested for one another in obtaining SPCs, and possibly shared the cost of tents, tools, etc. Perhaps, also, the Killingly group had a financial backer who paid for their passage and supplies in return for a cut of whatever gold they found. In all there were 21 passengers aboard the Schooner Willimantic.

The Mystic seaport ship database also holds information about the Willimantic. (Fig. 3.) The schooner was 105 feet in length, with a 26-foot 9-inch beam. The Willimantic had a square bow, two masts, and one deck. The ship had been commissioned for the California coasting trade, to make relatively short hops up and down the Pacific coast. The maiden voyage would be the only one where the schooner truly sailed the open seas.

After wringing what I could from the Mystic Seaport website, I still had questions I wanted answers to.

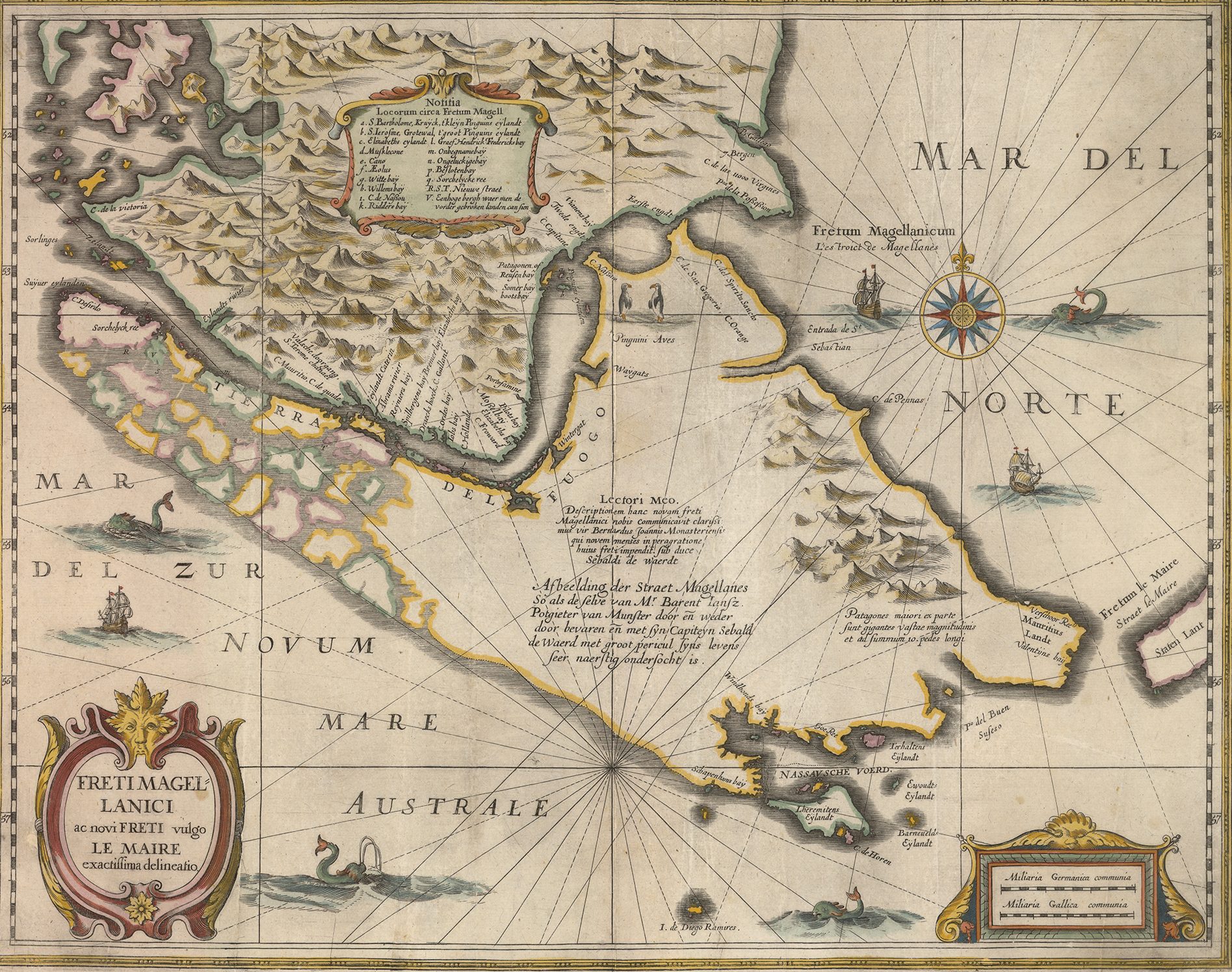

How long was Ebenezer’s sea journey around Cape Horn?

In distance traveled, the journey to San Francisco was about 15,000 miles. But how much time did it take? By searching online, I was able to find the Willimantic in Barnstable and Yarmouth, Sea Captains and Ship Owners (Fig. 4.). They gave the arrival for the Willimantic in San Francisco as November 2, 1849. That means a journey of 234 days with 20 passengers plus crew on a one-deck, 100-foot ship. That is pretty close quarters!

When would William and his group have passed Cape Horn and what would weather conditions have been like?

To answer this question, I searched for travelers who had rounded Cape Horn in 1849, and I found a happy few that give a marvelous feel for the journey.

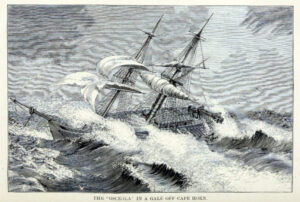

One of the best is Notes of a Voyage to California via Cape Horn, by Samuel C. Upham. With pictures! Judging by the pace of Upham’s trip on the Osceola, it would have taken the Willimantic about 100 days to make Cape Horn. They would reach the treacherous waters of the Cape in mid-June, the dead of winter for the Southern Hemisphere.

At any time of year, doubling the Cape was difficult due to wildly unpredictable weather and currents; there the Atlantic and Pacific ocean waters meet and battle. Attempting the passage mid-winter would have added severe storms and frigid weather to the mix. While we have no record of how difficult the voyage may have been, other seafarers who traveled around the Cape that winter reported weeks of bitter cold and having to continually sweep snow from the deck. Passengers ate salt pork and hard tack; they stayed in their bunks all day to counter the freezing temperatures. No fire was allowed in cabin or galley as the pitching bow of the schooner continually shipped water.

On the bright side, the young men from Killingly would encounter spectacular marvels along the way: novel varieties of bird and sea life, strange and wonderful landscapes, and new star constellations in the dark, night sky.

Did Ebenezer find any gold?

Very few Forty-Niners found much gold, and it’s doubtful that Ebenezer did. I haven’t found a record of his journey home, and so don’t have an accurate date for when Ebenezer left California. However, he and Harriet had a second son, Adelbert, in July 1853. We infer that Ebenezer was back by November 1852. Considering the trip home was an 8-month journey, he must have left California about January of 1852. Ebenezer’s sojourn in California lasted only two years. I’m thinking he didn’t find gold, or he might have stayed longer!

But at least two of Ebenezer’s Killingly friends did stay in the land of gold. Smith Mitchell is listed in the 1860 census as a dairyman in Fairfield, California. Isaac Hyde became a prosperous banker in Oakland, California, and appears in the Census as late as 1880.

Ebenezer went back to working in the textile industry when he returned to Connecticut. Can we blame him for losing further desire for high adventure?

MORE—See Part II—Write the Story: Around Cape Horn and Back Again!

MORE—See Part III—Getting It Out There: Around Cape Horn and Back Again!